Module 9: Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

Case studies: substance-abuse disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify substance abuse disorders in case studies

Case Study: Benny

The following story comes from Benny, a 28-year-old living in the Metro Detroit area, USA. Read through the interview as he recounts his experiences dealing with addiction and recovery.

Q : How long have you been in recovery?

Benny : I have been in recovery for nine years. My sobriety date is April 21, 2010.

Q: What can you tell us about the last months/years of your drinking before you gave up?

Benny : To sum it up, it was a living hell. Every day I would wake up and promise myself I would not drink that day and by the evening I was intoxicated once again. I was a hardcore drug user and excessively taking ADHD medication such as Adderall, Vyvance, and Ritalin. I would abuse pills throughout the day and take sedatives at night, whether it was alcohol or a benzodiazepine. During the last month of my drinking, I was detached from reality, friends, and family, but also myself. I was isolated in my dark, cold, dorm room and suffered from extreme paranoia for weeks. I gave up going to school and the only person I was in contact with was my drug dealer.

Q : What was the final straw that led you to get sober?

Benny : I had been to drug rehab before and always relapsed afterwards. There were many situations that I can consider the final straw that led me to sobriety. However, the most notable was on an overcast, chilly October day. I was on an Adderall bender. I didn’t rest or sleep for five days. One morning I took a handful of Adderall in an effort to take the pain of addiction away. I knew it wouldn’t, but I was seeking any sort of relief. The damage this dosage caused to my brain led to a drug-induced psychosis. I was having small hallucinations here and there from the chemicals and a lack of sleep, but this time was different. I was in my own reality and my heart was racing. I had an awful reaction. The hallucinations got so real and my heart rate was beyond thumping. That day I ended up in the psych ward with very little recollection of how I ended up there. I had never been so afraid in my life. I could have died and that was enough for me to want to change.

Q : How was it for you in the early days? What was most difficult?

Benny : I had a different experience than most do in early sobriety. I was stuck in a drug-induced psychosis for the first four months of sobriety. My life was consumed by Alcoholics Anonymous meetings every day and sometimes two a day. I found guidance, friendship, and strength through these meetings. To say early sobriety was fun and easy would be a lie. However, I did learn it was possible to live a life without the use of drugs and alcohol. I also learned how to have fun once again. The most difficult part about early sobriety was dealing with my emotions. Since I started using drugs and alcohol that is what I used to deal with my emotions. If I was happy I used, if I was sad I used, if I was anxious I used, and if I couldn’t handle a situation I used. Now that the drinking and drugs were out of my life, I had to find new ways to cope with my emotions. It was also very hard leaving my old friends in the past.

Q : What reaction did you get from family and friends when you started getting sober?

Benny : My family and close friends were very supportive of me while getting sober. Everyone close to me knew I had a problem and were more than grateful when I started recovery. At first they were very skeptical because of my history of relapsing after treatment. But once they realized I was serious this time around, I received nothing but loving support from everyone close to me. My mother was especially helpful as she stopped enabling my behavior and sought help through Alcoholics Anonymous. I have amazing relationships with everyone close to me in my life today.

Q : Have you ever experienced a relapse?

Benny : I experienced many relapses before actually surrendering. I was constantly in trouble as a teenager and tried quitting many times on my own. This always resulted in me going back to the drugs or alcohol. My first experience with trying to become sober, I was 15 years old. I failed and did not get sober until I was 19. Each time I relapsed my addiction got worse and worse. Each time I gave away my sobriety, the alcohol refunded my misery.

Q : How long did it take for things to start to calm down for you emotionally and physically?

Benny : Getting over the physical pain was less of a challenge. It only lasted a few weeks. The emotional pain took a long time to heal from. It wasn’t until at least six months into my sobriety that my emotions calmed down. I was so used to being numb all the time that when I was confronted by my emotions, I often freaked out and didn’t know how to handle it. However, after working through the 12 steps of AA, I quickly learned how to deal with my emotions without the aid of drugs or alcohol.

Q : How hard was it getting used to socializing sober?

Benny : It was very hard in the beginning. I had very low self-esteem and had an extremely hard time looking anyone in the eyes. But after practice, building up my self-esteem and going to AA meetings, I quickly learned how to socialize. I have always been a social person, so after building some confidence I had no issue at all. I went back to school right after I left drug rehab and got a degree in communications. Upon taking many communication classes, I became very comfortable socializing in any situation.

Q : Was there anything surprising that you learned about yourself when you stopped drinking?

Benny : There are surprises all the time. At first it was simple things, such as the ability to make people smile. Simple gifts in life such as cracking a joke to make someone laugh when they are having a bad day. I was surprised at the fact that people actually liked me when I wasn’t intoxicated. I used to think people only liked being around me because I was the life of the party or someone they could go to and score drugs from. But after gaining experience in sobriety, I learned that people actually enjoyed my company and I wasn’t the “prick” I thought I was. The most surprising thing I learned about myself is that I can do anything as long as I am sober and I have sufficient reason to do it.

Q : How did your life change?

Benny : I could write a book to fully answer this question. My life is 100 times different than it was nine years ago. I went from being a lonely drug addict with virtually no goals, no aspirations, no friends, and no family to a productive member of society. When I was using drugs, I honestly didn’t think I would make it past the age of 21. Now, I am 28, working a dream job sharing my experience to inspire others, and constantly growing. Nine years ago I was a hopeless, miserable human being. Now, I consider myself an inspiration to others who are struggling with addiction.

Q : What are the main benefits that emerged for you from getting sober?

Benny : There are so many benefits of being sober. The most important one is the fact that no matter what happens, I am experiencing everything with a clear mind. I live every day to the fullest and understand that every day I am sober is a miracle. The benefits of sobriety are endless. People respect me today and can count on me today. I grew up in sobriety and learned a level of maturity that I would have never experienced while using. I don’t have to rely on anyone or anything to make me happy. One of the greatest benefits from sobriety is that I no longer live in fear.

Case Study: Lorrie

Figure 1. Lorrie.

Lorrie Wiley grew up in a neighborhood on the west side of Baltimore, surrounded by family and friends struggling with drug issues. She started using marijuana and “popping pills” at the age of 13, and within the following decade, someone introduced her to cocaine and heroin. She lived with family and occasional boyfriends, and as she puts it, “I had no real home or belongings of my own.”

Before the age of 30, she was trying to survive as a heroin addict. She roamed from job to job, using whatever money she made to buy drugs. She occasionally tried support groups, but they did not work for her. By the time she was in her mid-forties, she was severely depressed and felt trapped and hopeless. “I was really tired.” About that time, she fell in love with a man who also struggled with drugs.

They both knew they needed help, but weren’t sure what to do. Her boyfriend was a military veteran so he courageously sought help with the VA. It was a stroke of luck that then connected Lorrie to friends who showed her an ad in the city paper, highlighting a research study at the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH.) Lorrie made the call, visited the treatment intake center adjacent to the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, and qualified for the study.

“On the first day, they gave me some medication. I went home and did what addicts do—I tried to find a bag of heroin. I took it, but felt no effect.” The medication had stopped her from feeling it. “I thought—well that was a waste of money.” Lorrie says she has never taken another drug since. Drug treatment, of course is not quite that simple, but for Lorrie, the medication helped her resist drugs during a nine-month treatment cycle that included weekly counseling as well as small cash incentives for clean urine samples.

To help with heroin cravings, every day Lorrie was given the medication buprenorphine in addition to a new drug. The experimental part of the study was to test if a medication called clonidine, sometimes prescribed to help withdrawal symptoms, would also help prevent stress-induced relapse. Half of the patients received daily buprenorphine plus daily clonidine, and half received daily buprenorphine plus a daily placebo. To this day, Lorrie does not know which one she received, but she is deeply grateful that her involvement in the study worked for her.

The study results? Clonidine worked as the NIDA investigators had hoped.

“Before I was clean, I was so uncertain of myself and I was always depressed about things. Now I am confident in life, I speak my opinion, and I am productive. I cry tears of joy, not tears of sadness,” she says. Lorrie is now eight years drug free. And her boyfriend? His treatment at the VA was also effective, and they are now married. “I now feel joy at little things, like spending time with my husband or my niece, or I look around and see that I have my own apartment, my own car, even my own pots and pans. Sounds silly, but I never thought that would be possible. I feel so happy and so blessed, thanks to the wonderful research team at NIDA.”

Candela Citations

- Liquor store. Authored by : Fletcher6. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Bunghole_Liquor_Store.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Benny Story. Provided by : Living Sober. Located at : https://livingsober.org.nz/sober-story-benny/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- One patientu2019s story: NIDA clinical trials bring a new life to a woman struggling with opioid addiction. Provided by : NIH. Located at : https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/treatment/one-patients-story-nida-clinical-trials-bring-new-life-to-woman-struggling-opioid-addiction . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Treating alcoholism through a narrative approach. Case study and rationale.

S rabinowitz.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

A case study illustrates the narrative or story-telling approach to treating alcoholism. We discuss the rationale for this method and describe how it could be useful in family practice for treating people with alcohol problems.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Rabinowitz S., Maoz B., Weingarten M., Kasan R. Listening to patients' stories. Storytelling approach in family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 1994 Dec;40:2098–2102. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- PDF (672.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Robert’s story

Robert was living with an alcohol addiction and was homeless for over 25 years. He was well known in the local community and was identified as one of the top 100 A&E attendees at the Local General Hospital.

He drank all day every day until he would pass out and this was either in the town centre or just by the roadside. In addition, Robert was also incontinent and really struggled with any meaningful communication or positive decision making due to his alcohol usage. This often resulted in local services such as police, ambulance being called in to help. He had no independent living skills and was unable to function without alcohol.

In addition, and due to his lifestyle and presenting behaviours, Robert had a hostile relationship with his family and had become estranged from them for a long period of time.

Robert needed ongoing support and it was identified at the General Hospital that if he was to carry on “living” the way he currently was, then he wouldn’t survive another winter.

On the back of this, Robert was referred to Calico who organised a multi-disciplinary support package for him, which included support with housing as part of the Making Every Adult Matter programme.

After some initial challenges, Robert soon started to make some positive changes.

The intensive, multidisciplinary support package taught him new skills to support him to live independently, sustain his tenancy and make some positive lifestyle changes which in turn would improve his health and wellbeing.

This included providing daily visits in the morning to see Robert and to support him with some basic activities on a daily/weekly basis. This included getting up and dressed; support with shopping and taking to appointments; guidance to help make positive decisions around his associates; support about his benefits and managing his money. In addition, he was given critical support via accessing local groups such as RAMP (reduction and motivational programme) and Acorn (drugs and alcohol service), as well as 1 to 1 sessions with drugs workers and counsellors to address his alcohol addiction.

After six months Robert continued to do well and was leading a more positive lifestyle where he had greatly reduced his A&E attendance. He had significantly reduced his alcohol intake with long periods of abstinence and was now able to communicate and make positive decisions around his lifestyle.

Critically he had maintained his tenancy and continued to regularly attend local groups and other support for his alcohol addiction and had reconnected with some of his family members.

By being able to access these community resources and reduce his isolation he is now engaged in meaningful activities throughout the day and has been able to address some of his critical issues. A small but significant example is that Robert is now wearing his hearing aids which means that he can now interact and communicate more effectively.

CASE REPORT article

Case report: diagnostic challenges in a patient with alcohol use disorder that developed following a stroke.

- 1 Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, United States

- 2 Addiction & Substance Use Rehabilitation, Westchester Behavioral Health Center, White Plains, NY, United States

Patients with comorbid neurological and psychiatric diseases often face considerable impairment, causing challenges that pervade many aspects of their lives. Symptoms can be especially taxing when one or more of these conditions is severely disabling, as the resulting disability can make it more challenging to address comorbidities. For clinicians, such patients can be quite difficult to both diagnose and treat given the immense potential for overlap between the underlying psychiatric and neurologic causes of their symptoms—as well as the degree to which they might exacerbate or, conversely, mask one another. These intricate relationships can also obscure the workup of more acute pathologies, such as alcohol withdrawal and delirium. This report details the complex history and clinical challenges in a 54-year-old man who was no longer able to work after developing multiple neurologic deficits from a left MCA stroke a decade earlier. The intellectual and motor disabilities he faced in the aftermath of his stroke were subsequently compounded by a steady increase in alcohol consumption, with his behavior ultimately progressing to severe alcohol use disorder. The coinciding neurologic and psychiatric manifestations obfuscate the workup—and therefore the management—of his major depressive disorder. In pursuit of the optimal approach to address these comorbid conditions and promote recovery, an investigation into possible mechanisms by which they are interconnected revealed several potential neuropsychiatric explanations that suggest targets for future therapeutic strategies.

1. Introduction

Following a stroke, patients can develop behavioral changes due to a variety of underlying mechanisms. Lesions in specific anatomic regions of the brain have well-documented stereotypical manifestations that might explain some of these behaviors ( 1 ). Behavioral changes can also develop as coping mechanisms to deal with the wide array of psychosocial stressors that arise after a large stroke ( 2 , 3 ). While these disparate pathophysiological processes may result in the same ultimate behavioral consequences for patients, they warrant scrutiny from a clinical perspective. It is crucial to determine if one mechanism or another is predominantly contributing to their symptoms, if the changes can be altogether better explained by an alternative unrecognized mechanism, and how these processes might interact with one another. Not only does the investigation of these questions allow clinicians to gain a more comprehensive understanding of their patients, but it can also potentially improve outcomes, as the optimal therapeutic approach is often influenced by the predominant underlying pathophysiology ( 4 ). To complicate this further, patients with large strokes often present with additional neurologic deficits (e.g., aphasia) that pose nuanced diagnostic challenges. This report describes the case of a 54-year-old man who developed an alcohol use disorder—on top of other complications—over the decade following a left MCA stroke. The purpose of this case report is to illustrate the nature of these diagnostic challenges and to suggest a strategic framework for tackling similarly complex cases.

2. Case description

The patient of interest is a 54-year-old man with a history of left MCA stroke, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use disorder, and major depressive disorder. He has been hospitalized multiple times for clinical monitoring of alcohol withdrawal. Most recently, this patient presented to the emergency department at an outside hospital with symptoms of alcohol withdrawal including tremors, diaphoresis, and anxiety. After completing alcohol detoxification, he began inpatient rehabilitation for alcohol use disorder.

Prior to his stroke, this patient had been a “social drinker,” consuming about 2 drinks per week. He relates that alcohol was not interfering with his life. That year, however, he suffered a left MCA stroke, resulting in persistent residual deficits that include right-sided weakness, expressive aphasia, and mild cognitive impairment. Over the course of the next several years, he gradually began drinking alcohol more heavily. He reports the problematic drinking started after he left his intellectually demanding occupation and began collecting disability benefits due to the cognitive impairment. Furthermore, he was unable to engage in other activities he had previously enjoyed, such as running, due to residual right-sided weakness throughout his body. Then, a close family member of his died of a myocardial infarction. In the years since the stroke, he endorses becoming “socially withdrawn” and feeling “useless,” which have contributed to a chronically depressed mood and an inability to “enjoy life as [he] used to.” Also during this timeframe, his diabetes progressed, and the patient began treatment with insulin. This progression was associated with new-onset peripheral neuropathy, which required daily gabapentin. Eventually, his drinking increased to a pint of vodka daily, leading numerous consequences in his life including medical and relationship difficulties.

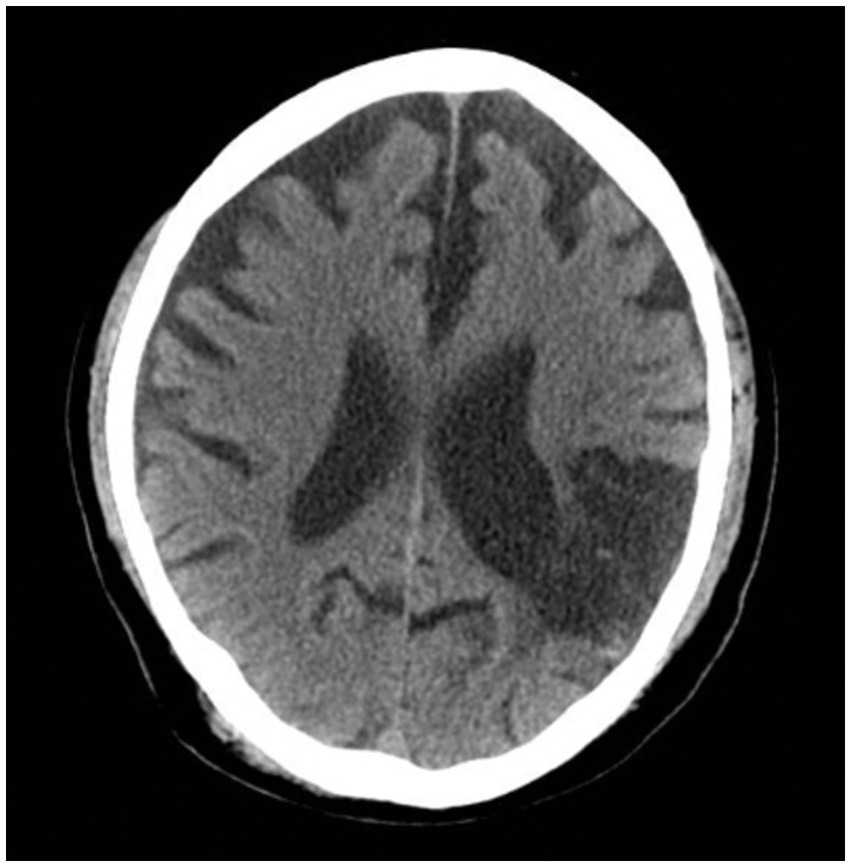

With treatment, he was able to maintain sobriety for a year before a fulminant relapse, again drinking a pint of vodka daily, which led to an inpatient rehabilitation. At that time, he was discharged on oral acamprosate and long-acting injectable naltrexone. However, he began drinking again, ultimately presenting with acute withdrawal to an outside hospital to make another attempt to address his alcohol use disorder. While in the hospital, medical workup was unremarkable. A non-contrast CT scan of the head ( Figure 1 ) was ordered and showed no acute changes. Chronic changes, which had previously been observed on CT, included the following:

1. There is moderate, diffuse ventricular and sulcal prominence consistent with volume loss, greater than expected for age.

2. There is a large region of encephalomalacia in the left posterior frontal and parietal lobes in a left MCA distribution. There is indistinctness of the gray-white interface in the affected region.

Figure 1 . Non-contrast CT scan obtained from outside hospital.

Alcohol withdrawal was managed with a symptom-triggered regimen of IV lorazepam and oral chlordiazepoxide according to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol ( 5 ). After 24 h without requiring benzodiazepines, he was admitted for the current short-term rehabilitation.

Upon admission to the inpatient rehabilitation facility, the patient exhibited intermittent states of confusion without agitation or aggressive behavior. In addition to his baseline expressive aphasia, mental status examination was notable for not knowing where he was, increased distractibility, and disorganized speech. He also became visibly frustrated when asked to name the current president and the date and said he was “confused because everyone keeps asking that question.” Staff members were in agreement that this mental status was an obvious and abrupt deterioration from his baseline during the recent admission over the summer. Therefore, the clinical team obtained collateral history from his wife to confirm chart review of his medical and psychiatric history, including alcohol use and premorbid functioning. On physical exam, he also had a gaze-evoked left-beating nystagmus. Given concern for possible Wernicke encephalopathy in the setting of chronic alcohol use, IM thiamine was administered (to augment the standing oral thiamine started during his detoxification). Several days later, his symptoms remain unchanged.

3. Discussion

This case highlights multiple meaningful, thought-provoking diagnostic challenges. One such challenge is establishing the most plausible explanations for altered mental status in this patient. Acutely altered mental status has numerous possible etiologies, some of which can be especially difficult to rule out given the challenges associated with taking the history of an altered patient. With the acute onset of disorientation and inattention, the patient likely experienced hypoactive delirium, a condition that is typically secondary to medical complications and/or medications.

Upon further inspection of his outside hospital course immediately prior to admission, it was discovered that while no benzodiazepines had been administered in the final 24 h of his hospitalization, he had been given a total of 800 mg of chlordiazepoxide over the 24 h leading up to his final dose. While this might have been sufficient to induce delirium even in a younger and healthier patient, the patient in this case has a multitude of risk factors that make him susceptible. Some of these factors include hospitalization, history of stroke, alcohol use disorder, alcohol withdrawal, depression, diabetes, and polypharmacy, among others.

While the benzodiazepines are likely a contributing factor, it is necessary to consider additional etiologies and exacerbating circumstances that are possibly complicating his delirium, and life-threatening metabolic disturbances must be ruled out. Wernicke encephalopathy, for which chronic alcohol use is a major risk factor, presents with confusion, oculomotor dysfunction, and gait ataxia in the setting of thiamine deficiency. This condition, however, is less convincing of an etiology in the setting of daily thiamine supplementation during his prior hospitalization. Rather, it is more likely that the nystagmus is an incidental exam finding caused by a physiologic end-point nystagmus.

Another cause of delirium is polypharmacy. In addition to benzodiazepines, he is on a medication regimen that consists of metoprolol, aspirin, gabapentin, duloxetine, atorvastatin, acetaminophen, naltrexone, acamprosate, and several others. Gabapentin, for example, may have increased the risk of withdrawal delirium. Furthermore, there is a lack of strong evidence to support the use of antidepressants, such as duloxetine, to treat depression in patients with alcohol use disorder. Regardless of whether polypharmacy was an underlying etiology of the delirium, his extensive medication list warranted review to assess for drug–drug interactions and to determine if any medications could be eliminated or reduced. When managing patient cases with similarities to this one, close review and verification of medication lists is imperative.

In addition to analyzing the complex nature of his delirium, a second fascinating issue in this patient is the conceivable connection between his stroke and the ensuing onset of his alcohol use disorder. In the aftermath of a severe stroke such as the one this patient experienced, there are several possible explanations for the development of a new-onset alcohol use disorder. An investigation into the predominant neuropsychiatric mechanism is crucial to guide the overarching therapeutic approach. Plausible mechanisms to explain the change in behavior after his stroke include maladaptive coping mechanisms in the setting of new psychosocial stressors ( 2 , 3 ), cerebrovascular tissue injury leading to impaired neurological functioning ( 1 , 6 – 8 ), and decompensation of a previously well-masked psychiatric illness in the setting of his stroke ( 9 ).

The chronic depression that the patient endorses is a common symptom in patients who have survived a stroke: the prevalence of depression at any time after experiencing a stroke is estimated to be 29 percent ( 2 ). This rate was shown to be significantly elevated in patients with some of the risk factors seen in Mr. A, including greater degrees of disability, cognitive impairment, and stroke severity. Mr. A suffered a significant decrease in functional status following his stroke, never returning to work afterwards. On an individual level, these circumstances were compounded by the fact that 2 years after the stroke, a close family member died. This highlights the importance of obtaining detailed histories in patients with presentations similar to that of Mr. A, as this might help to capture psychosocial stressors and other complicating patients factors that can be addressed by the care team.

Previous research has also suggested that patients with depression after a stroke have different attitudes on coping strategies than do patients without depression: in their responses on a 20-item checklist, patients with depression expressed decreased levels of both rational cognitive appraisal (i.e., taking things “one step at a time”) and behavioral action (i.e., taking “positive action to regain strength”) ( 3 ). This finding, which might be explained by underlying patient attributes, is insufficient to establish causation. It does, however, convey prognostic utility, establishing that this patient is at higher risk of displaying an attitude that promotes maladaptive coping strategies in response to psychosocial stressors. This should be taken into consideration for patients like Mr. A, in whom appropriate education regarding coping mechanisms is crucial.

In contrast to these psychological explanations, an alternative pathophysiology underlying alcohol use disorder in this patient might be that it developed as a direct sequela of his initial ischemic insult. Cognitive deficits of varying severities are seen in about 46 percent of patients 6 months following ischemic stroke ( 6 ). Consequently, male stroke patients between the ages of 18 and 50 are 3.2 times more likely to become unemployed within the first 8 years after a stroke compared to healthy peers ( 7 ). In the general population, cognitive impairment and unemployment are both independent risk factors for alcohol use disorder ( 8 ).

Other recent neuropsychiatric research has demonstrated that global cortical thinning, a common finding in patients who have had strokes, is associated with an increased risk for alcohol use disorder ( 1 ). As was noted on his most recent CT scan ( Figure 1 ), his brain demonstrates diffuse volume loss as well as a large region of chronic encephalomalacia. While this isolated finding does not provide a complete picture of how (if at all) parenchymal damage contributed to the alcohol use in this specific individual, this literature does highlight the concept that structural consequences following a stroke likely play a role in modulating behavioral changes down the line.

The association of alcohol use disorder with comorbid mood disorders has been described in multiple large cohort studies. Using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, one study quantified the degree to which mood disorders correlated with lifetime risk of alcohol use disorder ( 9 ). The study elucidated that the odds ratio of having a history of any mood disorder was 2.4. While bipolar I disorder was the largest risk factor among the individual mood disorders, major depressive disorder was another independent risk factor for alcohol use disorder, with an odds ratio of 1.9.

Extrapolating to this patient, it is possible that he suffered from an undiagnosed mood disorder, such as major depressive disorder, before the stroke. If that were the case, the stroke and its associated stressors would likely have exacerbated his symptoms, ultimately contributing to his alcohol use disorder. Evidence to support this mechanism includes a neuroanatomical localization study that elucidated the anterior temporal cortex as a site frequently involved in strokes that are complicated by post-stroke depression ( 10 ). Of particular interest in this patient is the observation that this (anterior temporal) cortical territory comprised a significant portion of the damaged tissue, suggesting yet another feasible mechanism of behavioral change.

4. Conclusion

While the consideration of complex psychiatric and neurologic mechanisms can enhance the diagnostic approach in a patient like this, many questions remain unanswered. Therefore, clinicians should continue to investigate the fascinating and intricate array of pathophysiological mechanisms underlying alcohol use disorder in patients recovering from a stroke. Based on the evidence that already exists, the overall progression might be driven by several distinct processes, ranging from maladaptive psychological coping mechanisms to ischemic damage in specific neuroanatomic regions to exacerbations of underlying mood disorders. According to Occam’s razor, these seemingly separate processes might all be sequelae of one shared principal lesion. However, until that lesion is identified, there are numerous mechanisms, spanning multiple disciplines, that are worthwhile to explore as possible therapeutic targets.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

JZ and NK: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Mavromatis, LA, Rosoff, DB, Cupertino, RB, Garavan, H, Mackey, S, and Lohoff, FW. Association between brain structure and alcohol use behaviors in adults: a Mendelian randomization and Multiomics study. JAMA Psychiat . (2022) 79:869–78. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2196

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Ayerbe, L, Ayis, S, Wolfe, CD, and Rudd, AG. Natural history, predictors and outcomes of depression after stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry . (2013) 202:14–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107664

3. Sinyor, D, Amato, P, Kaloupek, DG, Becker, R, Goldenberg, M, and Coopersmith, H. Post-stroke depression: relationships to functional impairment, coping strategies, and rehabilitation outcome. Stroke . (1986) 17:1102–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.6.1102

4. Attilia, F, Perciballi, R, Rotondo, C, Capriglione, I, Iannuzzi, S, Attilia, ML, et al. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic methods. Riv Psichiatr . (2018) 53:118–22. doi: 10.1708/2925.29413

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Holleck, JL, Merchant, N, and Gunderson, CG. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med . (2019) 34:1018–24. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04899-7

6. Kelly-Hayes, M, Beiser, A, Kase, CS, Scaramucci, A, D'Agostino, RB, and Wolf, PA. The influence of gender and age on disability following ischemic stroke: the Framingham study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis . (2003) 12:119–26. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3057(03)00042-9

7. Maaijwee, NA, Rutten-Jacobs, LC, Arntz, RM, Schaapsmeerders, P, Schoonderwaldt, HC, van Dijk, EJ, et al. Long-term increased risk of unemployment after young stroke: a long-term follow-up study. Neurology . (2014) 83:1132–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000817

8. Corral, M, Holguín, SR, and Cadaveira, F. Neuropsychological characteristics of young children from high-density alcoholism families: a three-year follow-up. J Stud Alcohol . (2003) 64:195–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.195

9. Hasin, DS, Stinson, FS, Ogburn, E, and Grant, BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry . (2007) 64:830–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830

10. Mayberg, HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci . (1997) 9:471–81. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.471

Keywords: case report, substance use disorder, delirium, coping strategies, polypharmacy

Citation: Zeitlin J and Kotbi N (2023) Case report: Diagnostic challenges in a patient with alcohol use disorder that developed following a stroke. Front. Psychiatry . 14:1116922. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1116922

Received: 06 December 2022; Accepted: 23 March 2023; Published: 12 April 2023.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2023 Zeitlin and Kotbi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jacob Zeitlin, amh6NDAwMUBtZWQuY29ybmVsbC5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Case Study: Benny. The following story comes from Benny, a 28-year-old living in the Metro Detroit area, USA. Read through the interview as he recounts his experiences dealing with addiction and recovery. Q: How long have you been in recovery? Benny: I have been in recovery for nine years. My sobriety date is April 21, 2010.

This case study presents the diagnosis and treatment of a male patient with an alcohol use disorder (AUD). Although medications are helpful in AUD, nurse practitioners must be cognizant when combining them with other approaches, such as therapy. Some clinicians prefer to control AUD use before treating other issues, under the theory that alcohol can obscure and aggravate underlying physical ...

This case study is an attempt to assess the impact of psychiatric social work intervention in person with alcohol dependence. Psychiatric social work intervention (brief intervention) was provided ...

A case study illustrates the narrative or story-telling approach to treating alcoholism. We discuss the rationale for this method and describe how it could be useful in family practice for treating people with alcohol problems. A case study illustrates the narrative or story-telling approach to treating alcoholism. We discuss the rationale for ...

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is marked by an inability to stop or reduce drinking despite impaired social or interpersonal functioning, consequential to a physical or psychological dependence. 1 Nearly 14 million adults in the United States meet diagnostic criteria for AUD, yet less than 10% of adults diagnosed AUD receive pharmacological treatment within 1 year, if at all. 2 Treatment of AUD is ...

chronic alcoholism and highlights the significance of timely screening and early intervention for at-risk alcohol use. DCM is characterized by dilation and impaired contraction of one or both ventricles and is caused by a variety of disorders such as genetic mutations, infections, autoimmune disorders, toxins and ...

Alcoholism and family relations: a case study wi th the application of the calgary model In this way, we ide ntify i mportant biop sychosocial o utcomes in Mr. Carnation's family, requiring ...

Dr. Andrew Z. Fenves: This 54-year-old man with a history of alcohol use disorder was admitted to the hospital with concerns about alcohol withdrawal symptoms. He had recent binges in which he ...

Case studies; Robert's story; Robert's story. Robert was living with an alcohol addiction and was homeless for over 25 years. He was well known in the local community and was identified as one of the top 100 A&E attendees at the Local General Hospital.

The association of alcohol use disorder with comorbid mood disorders has been described in multiple large cohort studies. Using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, one study quantified the degree to which mood disorders correlated with lifetime risk of alcohol use disorder . The study elucidated that ...