An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Nurse and patient activities and interaction on psychiatric inpatients wards: a literature review

Jessica sharac, paul mccrone, ramon sabes-figuera, emese csipke.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Issue date 2010 Jul.

Despite major developments in community mental health services, inpatient care remains an important yet costly part of the service system and patients who are admitted frequently spend a long period of time in hospital. It is, therefore, crucial to have a good understanding of activities that take place on inpatient wards.

To review studies that have measured nursing and patient activity and interaction on psychiatric inpatient wards.

Data sources and review methods

This literature review was performed by searching electronic databases and hand-checking reference lists.

The review identified 13 relevant studies. Most used observational methods and found that at best 50% of staff time is spent in contact with patients, and very little time is spent delivering therapeutic activities. Studies also showed that patients spend substantial time apart from staff or other patients.

On inpatient psychiatric wards, evidence over 35 years has found little patient activity or patient social engagement. The reasons for this trend and recommendations for the future are discussed.

Keywords: acute mental health, acute psychiatric ward, literature review, mental health nursing activity

Introduction

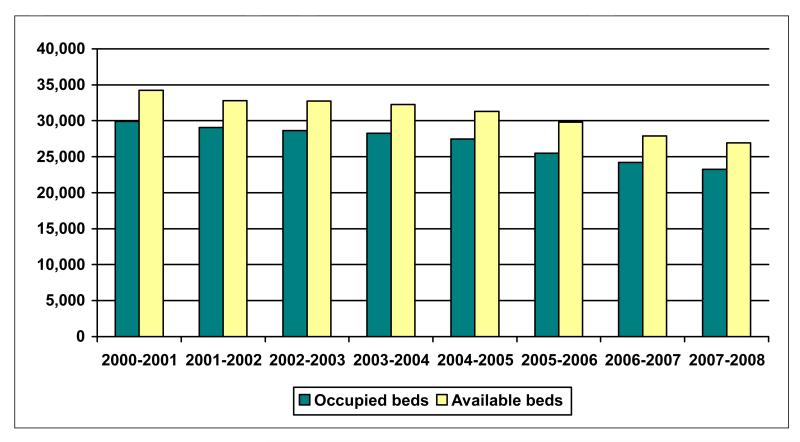

Research indicates that greater staff-patient interaction and greater patient activity (i.e. participation in therapeutic or social activities rather than being socially disengaged or spending time alone) in inpatient wards improves clinical outcomes for patients with mental illness ( Collins et al, 1985 ). The changing composition of UK mental health care service provision in recent years has though put a strain on acute mental health resources which has affected how nurses interact with and treat patients. This is mirrored in most western health care systems. The greater emphasis and spending on community-based mental health care has reduced the portion of the mental health care budget allocated to inpatient psychiatric care, leading to a reduction in the number of acute care and long-stay beds (this is illustrated for the UK in Figure 1 ), although the amount spent on inpatient care remains substantial.

Figure 1. Available and occupied inpatient beds for mental illness in England, 2000-2008.

Source: Department of Health, 2008

The average daily number of available psychiatric beds in England dropped from 67,122 in 1997-1998 to 26,929 in 2007-2008 ( Department of Health, 2008 ). Admitted patients are more likely to have psychotic disorders and in 2006/7 the median length of stay for these patients was 42 days, ( Information Centre, 2008 ). At a cost of £268 per bed-day of acute inpatient psychiatric care ( Curtis, 2008 ), this average length of stay would cost £11,256.

Given the reduction in acute beds, priority naturally goes to those patients who are more severely mentally ill, particularly for those who have been involuntary admitted or have major social problems ( Ryrie et al, 1998 ). Nurses report that they feel pressure to discharge patients who may not have yet fully recovered in order to free up beds ( Higgins et al, 1999 ). Due to the severity of the patient mix, staff members find it difficult to provide interaction and therapeutic activities as much of their time is spent looking after very ill patients.

In a 2004 survey by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health ( Garcia et al, 2005 ) it was found that although 64% of wards routinely offer social and leisure activities (e.g. going to the gym, bingo) and 73% practical therapeutic activities (e.g. money management, cooking skills), psychological therapies were not routinely offered on the majority of acute psychiatric wards. Art therapy was the most commonly available therapy, available in 49% of wards, compared to 35% for psychosocial interventions, and less than 20% for cognitive behavioural therapy, solution focused behavioural therapy and family therapy. Besides the difficulty of staff having the time to offer activities because they are occupied with taking care of very ill patients, the reports suggest that the lack of activities and talking therapies may be partially explained by the use of agency staff, by the culture of the psychiatric wards, and by staff shortages, especially of occupational therapists and psychologists.

Assessing both the extent of interaction between patients and staff and patients’ participation in activities may be important for both clinical and economic reasons. It is helpful, therefore, to determine the extent of this input. This might help in planning for the costs of specific units by determining the appropriate amount and grade of staff members. Nursing and other professional time comes with a cost, and whilst most studies and payment systems currently focus on the average cost of an inpatient day there are reasonable grounds for deriving per patient inpatient costs. These grounds include the requirement in economic evaluations that costs reflect the actual resources used. A further, linked, reason for using actual per patient costs is that any form of prospective payment (such as ‘Payment by Results’ in the UK) should link prices/tariffs as closely as possible to care received.

Most of the high costs of inpatient care are attributable to personnel costs. Beecham et al (2003) reported that staff costs account for 70% of the costs of child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient units. Similarly, McKechnie et al (1982) found that the percentage of costs attributable to staffing varied by the type of unit, but ranged from 74-91% of total care and treatment costs of psychiatric wards.

Collins et al (1985) have suggested that clinical outcomes are associated with patient activity and social interaction. If this is the case, then devoting more staff time to direct (and hopefully therapeutic) patient activities and care could have a positive effect on patient care and may be cost-effective. Indeed, a study by Dodds and Bowles (2001) found that changing the allocation of nursing time from formal observation of inpatients to structured, individualised activities, which often took place on a one-to-one basis, improved patient-reported quality of care while the number of staff sicknesses and staffing costs decreased. The authors estimated that in a best case scenario, an inpatient ward could save up to £44,878 on staffing costs over a year if they adopted this change in nursing time allocation. Furthermore, research indicates that for patients, the most important aspect of quality inpatient care is that staff members take their time with and care for patients ( Hansson et al, 1993 ). Of course it should be stressed that staff time is not synonymous with therapeutic input. Merely spending more time with patients might not improve outcomes. However, given the above findings it does seem logical to expect improvements to be linked with what staff and patients do on wards and as such recording staff and patient activities seems a reasonable exercise.

The aims of this review are to (i) identify studies that have measured nursing and patient activity and interaction on psychiatric inpatient wards, (ii) compare methodologies used in these studies and (iii) examine how much time is typically spent in staff-patient interaction. Finally, we make suggestions for future work based on the findings.

A search strategy was employed to systematically identify published studies relevant to the literature review. Initially, the electronic databases EMBASE (1980-2008), MEDLINE (1950-2008), and PsycINFO (1806-2008) were searched with the following keywords: “inpatient”, “mental”, “psychiatric”, “hospitaliz(s)ed”, hospitaliz(s)ation”, “time”, and “activity”. A final check of the literature was made on 30 November 2009. Included studies were limited to those published after 1970, which were written in English, and which reported activity on psychiatric inpatient wards. Abstracts were reviewed by two authors (JS and PM) to assess eligibility for inclusion. The reference lists of included studies were checked (by PM) for further relevant literature. The criteria for inclusion were that (i) the study was based in an inpatient setting and (ii) that it measured or observed and recorded time spent by patients and/or staff on different activities. Given that studies differed substantially in their methods and contexts we did not attempt to combine the results in a formal way. In addition, given the study heterogeneity we did not have predetermined measures of quality but we do discuss study characteristics in the text.

The search strategy identified 86 papers of potential relevance. After reviewing abstracts two studies were initially included. A further 11 studies were included following examination of reference lists. Study characteristics are summarised in Table 1 . Four of the studies were performed in England, three in Australia, two in Scotland and one each in Finland, Canada, the USA and Northern Ireland. Before the findings from the studies are described we will summarise the methods used and make some inference about the quality of the studies.

Table 1. Methods of reviewed time and motion studies.

Methodological and quality issues.

Studies used data collected through interviews, questionnaires, audits of attendance registers, and observations of staff and patients on wards at varying time intervals, usually recorded with an observational instrument and coded according to specific categories.

(i) Interviews or questionnaires: Using this methodology, staff members are surveyed or interviewed about the time spent at work., In Ryrie et al’s (1998) study, staff members recorded their activity every 15 minutes over a seven-day period according to a set of pre-designated categories. The authors suggest that the seven-day period may not have been sufficiently representative and that some changes to staffing levels took place after the study. They also felt that 15-minute intervals may have been too long period to detect changes in activity. In another study (Bee et al., 2003), staff members were interviewed on a daily basis and reported all activities, but not the time spent, undertaken in the past hour as well as an estimate of the number of minutes spent in direct patient contact. This study covered more time periods than Ryrie et al and so may have picked up more fluctuation in activity levels. The authors considered the number of nurses surveyed (40) to be a limitation but this is in fact a relatively large sample compared to other studies. ( Ryrie et al used a sample of eight.) Neither of these studies included night shifts. The method of self-report of time spent has the advantage that it requires relatively small amounts of researcher time to complete. However, a disadvantage of this method is that, given the hectic pace on the inpatient ward, the staff members may have little time to complete the surveys or interviews and so may under- or over-report certain activities. There is also the danger of response bias, in which the staff members may self-report more patient contact than actually occurs.

(ii) Audits of attendance registers: Audits of attendance registers have been used to assess patient participation in group activities. This can be used as a verification tool for patient self-report of activities or in conjunction with an observational design as was done by Radcliffe and Smith (2007) . This method is helpful in measuring group activity without the time and effort required for observational studies and to double-check patients’ reports, which may be inaccurate due to confusion caused by symptoms or medication. The disadvantage is that it can be difficult to verify group attendance - some patients have difficulty concentrating and may drift in and out of group activities or attend for say 10 minutes of an hour-long activity. Radcliffe and Smith (2007) also point out that it is difficult to establish the accuracy with which activity leaders record attendance.

(iii) Observations of patients and staff: This has been the most commonly used method in studies reviewed. Researchers observe patients, staff or both for specified periods of time and record the activities they take part in, often using an observational instrument in which activities are designated into categories and coded according to category.

Altschul (1972) conducted one of the seminal observational studies of nursing activity. She observed 40 nurses in four wards of a Scottish hospital during four-hour periods over three- to four-week time periods. Interactions lasting three minutes or more were included and timed and the nature of the interaction recorded. Another Scottish study (supervised by Altschul) observed 14 charge nurses for 12 hours each ( Cormack, 1976 ). Activities were recorded and categorised. Whilst these were early studies, they were comparable in observation period and number of nurses included to later work.

A Canadian study observed patients and staff in three wards over a one-week period ( Willer et al, 1974 ). Each ward was observed 60 times. It is likely that observations did reflect accurately ward activity during that period, but as with other studies it is unclear whether one week is sufficient to draw conclusions. In an early study from the United States patient and staff activity on four inpatient wards was observed ( Fairbanks et al, 1977 ). Six 150-minute sessions of observation were conducted for each ward and one person was observed during that time. Inter-rater reliability was tested and found to be reasonable, although variability was quite high for observation of social activities.

In Australia, Sanson-Fisher et al (1979) made observations of patients and staff on a single ward. Two six-day periods of observation were used and during this time observers moved through the ward twice every hour and recorded activities taking place. Whilst limited to one ward it was an advantage that two periods (separated by six weeks) were used and also that a reliability test was conducted for 10% of observations. The percentage agreement between observers was between 83 and 100% depending on the activity type. This study was followed by the authors with a comparison of patient activity on two different wards ( Poole et al, 1981 ). Ten patients were selected from each ward and observed six times for five minutes. This does represent a relatively short period of total observation compared to other studies. In another Australian study, Sandford et al (1990) observed nursing activity when nursing numbers on wards differed. Initially observations were carried out on one ward over a 20-day period. Nurse numbers varied by day with either five, six or seven nurses being on duty. The impact of this on interactions was measured. Subsequently, nurse activity was observed in three wards over 12 weeks, allowing for natural fluctuations in staff numbers. In each case, nurses were observed every five minutes for five hours.

An in-depth analysis of the activities of seven inpatients in Finland was conducted by Lepola and Vanhanen (1997) as part of a more qualitative study. The patients were deliberately selected and the observation period was relatively short and as such the findings would not be generalisable. Elsewhere, Higgins et al (1999) observed all nurses and five patients in each of 11 sites. Activities were recorded very 15 minutes during all shifts over a one-week period. As with other studies, this period of time might be too short to ensure representativeness. Whittington and McLaughlin (2000) observed 20 nurses one at a time for one shift. This led the authors to call into question the representativeness of the data. Another limitation noted by the authors was that a convenience sample was used. This though does appear to be the norm in activity studies reviewed, and may not be as serious a problem as the short observation period. Indeed, a convenience sample may be the most practical (and least disruptive) way of conducting such studies.

The aforementioned study by Radcliffe and Smith (2007) observed activity in 16 wards and six hospitals. This was an advantage in terms of representing a wide spread of wards, but the observation period was relatively short (one week) and only three ten-minute observations per day were made.

The method of observation is popular and does appears to be the most accurate way of measuring activity as activities are recorded as they occur, so are not subject to recall bias of retrospective reports or response bias. However, the disadvantage of this method is that it is subject to the observer effect, in that staff members would know they were being watched and their actions recorded, so they may alter their usual schedules of patient care. It is especially common for observational studies to measure activity according to specific categories. Observation does though entail a relatively high level of input on the part of researchers.

Use of nurse time

Some studies that have assessed the use of nursing time have found reasonably similar amounts spent with patients: 48% ( Bee at al, 2006 ), 43% ( Whittington and McLaughlin, 2000 ), 50% ( Ryrie et al, 1998 ). Other studies have though demonstrated that higher grade nurses spend less of their time directly with patients: <30% ( Higgins et al, 1999 ) 1 , 27% ( Cormack et al, 1976 ), 29% ( Bee et al, 2006 ). Conversely they spend disproportionately more time on administrative tasks. In one study it has also been shown that time spent with patients has fallen over time for all grades of staff ( Higgins et al, 1999 ). Elsewhere, Sandford et al (1990) reported that only 15-18% of staff time was spent with patients and 31-34% with other staff members (with the remainder being spent alone), whilst Sanson-Fisher et al (1979) found that 24% of staff time was spent interacting with patients.

Although up to a half of staff time might be spent directly with patients, relatively little of this time appears to spent on providing specific therapeutic interventions: 4% ( Bee et al, 2006 ), 17% ( Whittington and McLaughlin, 2000 ), 13-20% ( Ryrie et al, 1998 ).

Social disengagement

In her early work, Altschul (1972) found that nurse-patient-interaction accounted for only 1% of observed time on wards, and only 30% of patients spent more than 1% in interactions with nurses. Willer et al (1974) later reported more positive results with patents spending only 39% of their time in ‘isolated passive behaviour’.

Another observational study ( Fairbanks et al, 1977 ) found that inpatients in four US psychiatric wards spent approximately 50% of their time alone and only about one-third of their time engaged in social activity. Time spent alone by patients was positively related to deviant behaviours and inversely related to social activity. Staff members spent more time than inpatients on social activity (average of 46% across the four wards) and spent significantly more time with other staff members than with patients, for example they were observed near patients less than 20% of the time but spent about twice as much time near other staff members. Before this, Willer et al (1974) had also demonstrated that staff spent twice as much time with other staff compared to time spent with patients. Interestingly, Sandford et al (1990) found that increasing staff numbers does not necessarily help as staff in their study then spent more time with other staff.

High rates of inpatient solitary behaviour were also reported in two Australian studies about thirty years ago. Sanson-Fisher et al (1978) observed that patients spent 49% of their time alone. In a subsequent study by the authors ( Poole et al, 1981 ) it was found that most of the patients’ time was spent in solitary behaviour in both the mental hospital ward (83%) and the general hospital psychiatric ward (62%), and little time was allocated to staff-patient interaction on both wards (9% and 13%, respectively).

Higgins et al (1999) found that patients spent only 4% of their time with staff, while they spent 28% of their time talking with other patients, watching TV, or doing nothing compared to 17% of their time in therapy. Slightly more patient time (15%) appeared to be spent in organised activities in the small study by Lepola et al (1997), but this was broadly defined as “activities related to the patient being together with other patients and the nurses”.

Radcliffe and Smith (2007) in their observational study of sixteen UK inpatient wards observed that patients spent the majority (84%) of their time socially disengaged, i.e. not interacting with staff members or other patients. Only 4% of patients’ time was spent in organised activities such as talking groups or art therapy.

Key findings

This review has identified studies that have examined how staff and patients on inpatient psychiatric wards spend their time and how much time is spent in staff-patient interaction. Studies published over a 35 year period from seven countries revealed quite consistent and clear findings: (i) on average around 50% of staff time is spent in contact with patients, (ii) the more senior the staff member, the smaller amount of time they spend with patients, (iii) amount of time spent delivering ‘therapy’ is probably in the region of 4-20%, (iv) relatively little patient time is spent in contact with staff and much is spent in isolation. There is also evidence to suggest that staff time with patients is reducing over time ( Higgins & Hurst, 1999 ) and that increasing staff numbers may not result in more time spent with patients ( Sandford et al, 1990 ). The findings that staff spend relatively little time in direct contact with patients and that patients spend little time with staff do not go hand-in-hand, because this depends on the staff-patient ratio.

The review also examined the methods used in the studies, most of which observed staff and/or patients over a period of time. A number of these studies were relatively small, including only limited numbers of staff. However, others were more representative in that they covered activity across different wards and sometimes across different hospitals. The majority of studies only observed activity for a limited period of time (sometimes only one week) and as such may not reflect typical activity patterns. This is though less of a concern in the multi-ward/site studies. This was recognised as a problem and it is perhaps inevitable given the limited research time that they would have been faced with. Most studies also only focussed on daytime shifts. A further recognised problem with the studies is that observers might influence the very activity that they are measuring.

Other methods to measure activity are self-report and collection of data from audits/administrative systems. Self-report by nurses may result in recall bias and an incentive to ‘inflate’ time spent in activities considered more ‘worthwhile’. Self-report and observational methods have been compared (on non-psychiatric wards) and differences found ( Ampt, et al 2007 ). Nurses reported significantly more time spent patient care (40% compared to 33% observed) and ward related activities (7% compared to 3% observed). However, whilst significant, these differences are not all that large. The authors also report that observational methods were more acceptable to staff than self-report, which perhaps reflects the busy workload on inpatient wards.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the review. First, the number of studies (13) identified was relatively low. This is surprising given the broad search strategy and the long inclusion period. This suggests that there is little interest in how staff and patients spend their time on psychiatric inpatient wards, or that research resources have not been made available to address this or that studies have not been published in academic journals. Second, they related to a long period of time and specific settings; as such it is challenging to draw firm messages from the findings. Third, we restricted ourselves to papers published since 1970 in English. Inpatient services have of course existed for a far longer period and it is likely that important work will have been published prior to 1970, and in non-English language journals. Unfortunately research time did not allow for a search of these. Fourth, ‘grey literature’ (e.g. unpublished reports) was not reviewed. Finally, only two papers were initially obtained through the electronic search. This was surprising, but searches of the reference lists did reveal substantially more literature.

Implications

It has been known for many years that what takes place on wards is important for patient outcomes. A landmark study by Wing and Brown (1970) compared three hospitals in the UK through 1960-1968 to determine if the ward atmosphere can affect patients’ clinical outcomes. The findings suggest that poor social environments in wards, in which patients spend much of their time not engaged in any activity, exacerbate mental illness. Although patients were not considered to differ in illness severity between the wards, they exhibited fewer negative symptoms in the ward with the best social environment. There were also changes exhibited over the years in all of the wards, for as the social environments improved so did the patients’ conditions; conversely, when two of the wards’ social environments deteriorated over time after initial improvements, the patients’ clinical conditions worsened and they became more socially withdrawn.

In a more recent study, researchers ( Hansen & Slevin, 1996 ) changed the structure of an inner-city acute care ward by introducing treatment planning meetings, group therapy, and community meetings. Two months after implementation, patients on the program ward reported significantly higher scores of involvement (energy in treatment and patient activity), support between staff and patients, and practical orientation (providing patients with practical skills in preparation for discharge).

The lack of structured activities and patient contact indicated in this literature review is thought to be due to a variety of issues. These issues include a more severe patient-mix so that staff members spend more time ‘containing’ than offering activities to patients, staff shortages of psychologists and occupational therapists, and a trend over time of nurses spending less of their time interacting with patients and more of their time on non-patient activities such as administrative duties.

Some options to improve social engagement and participation in group activities are that (i) activities could be offered that are able to be led by unqualified staff or unqualified staff could be trained to lead some groups (ii) efforts could be strengthened to recruit volunteers onto the wards to lead activities, (iii) the introduction of information technology onto the wards might be used to streamline administrative duties and paperwork to free up time for nurses to devote more time to caring for patients on a one-to-one basis.

It is also suggested that research into inpatient activity rely less on observational designs and includes service users’ input. As part of the NIHR Applied programme grant, the PERCEIvE study, researchers have designed a novel approach to measuring inpatient activity in which patients complete a questionnaire, the Client Services Receipt Inventory-Inpatient (CITRINE), as part of a researcher interview to report their group activities, staff contacts, and one-on-one time with nurses in the past week.

The key findings of this review are that despite evidence of the benefits of and official guidance for therapeutic interaction, reports of low activity and social engagement for patients have remained stable for 35 years and that limited nursing time is spent in direct contact with patients. It provokes the need for better exploration of how psychiatric inpatient staff members allocate their time on the ward within the constraints of limited acute care resources and how their time could be spent in more effective ways. This is especially important given that relatively few studies have addressed this topic which is likely to be of key interest to mental health professionals and patients.

Summary Statement.

What is already known about the topic.

Research indicates better social environments on inpatient psychiatric wards can improve patients’ clinical outcomes.

Over time, more money has been devoted to community rather than acute psychiatric care, reducing the number of acute beds and leading to more severely ill patients on wards. This trend has been posited to explain patients’ disengagement as nurses have little time for patient activities.

What this paper adds

Thirteen studies published over 1972-2007 indicated a steady trend of little patient activity or social engagement, with patients spending a majority of their time alone.

Nurses spend at most around half their time with patients and patient contact decreases as the nurse seniority increases.

This is for G-grade nurses. The authors reported that F-grade nurses spent around 45% of their time with patients.

- Altschul AT. Patient-Nurse Intercation: A Study of Interaction Patterns in Acute Psychiatric Wards. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1972. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ampt A, Westbrook J, Creswick N, Mallock N. A comparison of self-reported and observational work sampling techniques for measuring time in nursing tasks. Journal of Health Service Research and Policy. 2007;12:18–24. doi: 10.1258/135581907779497576. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bee PE, Richards DA, Loftus SJ, Baker JA, Bailey L, Lovell K, Woods P, Cox D. Mapping nursing activity in acute inpatient mental healthcare settings. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15(2):217–226. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beecham J, Chisholm D, O’Herlihy A, Astin J. Variations in the costs of child and adolescent psychiatric in-patient units. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;183:220–225. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.3.220. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Collins JF, Casey NA, Hickey RH, Twemlow SW, Ellsworth RB, Hyer L, Schoonover RA, Nesselroade JR. Treatment characteristics of psychiatric programs that correlate with patient community adjustment. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1985;41:299–308. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198505)41:3<299::aid-jclp2270410302>3.0.co;2-a. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cormack D. Psychiatric Nursing Observed. Royal College of Nursing of the United Kingdom; London: 1976. [ Google Scholar ]

- Curtis L. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. Personal Social Services Research Unit; Canterbury: 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Department of Health [accessed 18 November 2008];Hospital Activity Statistics. 2008 http://www.performance.doh.gov.uk/hospitalactivity/data_requests/index.htm .

- Dodds P, Bowles N. Dismantling formal observation and refocusing nursing activity in acute inpatient psychiatry: a case study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2001;8(2):183–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.0365d.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fairbanks LA, McGuire MT, Cole SR, Sbordone R, Silvers FM, Richards M, Akers J. The ethological study of four psychiatric wards: patient, staff, and system behaviours. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1977;13:193–209. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(77)90016-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia I, Kennett C, Quraishi M, Durcan G. Acute care 2004: a national survey of adult psychiatric wards in England. The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; London: 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hansen JT, Slevin C. The implementation of therapeutic community principles in acute care psychiatric hospital settings: an empirical analysis and recommendations for clinicians. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996;52(6):673–678. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199611)52:6<673::AID-JCLP9>3.0.CO;2-L. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hansson L, Bjorkman T, Berglund I. What is important in psychiatric inpatient care? Quality of care from the patient’s perspective. Quality Assurance in Health Care. 1993;5(1):41–47. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/5.1.41. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins R, Hurst K, Wistow G. Nursing acute psychiatric patients: a quantitative and qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(1):52–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00863.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hodges V, Sandford D, Elzinga R. The role of ward structure on nursing staff behaviours: an observational study of three psychiatric wards. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1986;73:6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02657.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Information Centre [accessed 18 November 2008];Hospital Episode Statistics. 2008 http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=203 .

- McKechnie AA, Rae D, May J. A comparison of in-patient costs of treatment and care in a Scottish psychiatric hospital. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;140:602–607. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.6.602. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Poole AE, Sanson-Fisher RW, Thompson V. Observations on the behaviour of patients in a state mental hospital and a general hospital psychiatric unit: a comparative study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1981;19:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(81)90036-x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Radcliffe J, Smith R. Acute in-patient psychiatry: how patients spend their time on acute psychiatric wards. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2007;31:167–170. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ryrie I, Agunbiade D, Brannock L, Maris-Shaw A. A survey of psychiatric nursing practice in two inner city acute admission wards. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27:848–854. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00575.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health . Acute problems: a survey of the quality of care in acute psychiatric wards. The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; London: 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sandford DA, Elzinga RH, Iversen RA. A quantitative study of nursing staff interactions in psychiatric wards. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1990;81:46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb06447.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanson-Fisher RW, Desmond, Poole A, Thompson V. Behaviour patterns within a general hospital psychiatric unit: an observational study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1979;17:317–332. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90004-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schanding D, Garber RL, Siomopoulos V. A small study on how the staff on an inpatient psychiatric unit spends its time. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 1982;20(2):91–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.1982.tb00157.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whittington D, McLaughlin C. Finding time for patients: an exploration of nurses’ time allocation in an acute psychiatric setting. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2000;7:259–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2000.00291.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Willer B, Stasiak E, Pinfold P, Rogers M. Acivity patterns and the use of space by patients and staff on the psychiatric ward. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal. 1974;19:457–462. doi: 10.1177/070674377401900503. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wing JK, Brown GW. Institutionalism and Schizophrenia. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1970. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (163.3 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES