Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What the data says about abortion in the U.S.

Pew Research Center has conducted many surveys about abortion over the years, providing a lens into Americans’ views on whether the procedure should be legal, among a host of other questions.

In a Center survey conducted nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision that ended the constitutional right to abortion , 62% of U.S. adults said the practice should be legal in all or most cases, while 36% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Another survey conducted a few months before the decision showed that relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the issue .

Find answers to common questions about abortion in America, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, which have tracked these patterns for several decades:

How many abortions are there in the U.S. each year?

How has the number of abortions in the u.s. changed over time, what is the abortion rate among women in the u.s. how has it changed over time, what are the most common types of abortion, how many abortion providers are there in the u.s., and how has that number changed, what percentage of abortions are for women who live in a different state from the abortion provider, what are the demographics of women who have had abortions, when during pregnancy do most abortions occur, how often are there medical complications from abortion.

This compilation of data on abortion in the United States draws mainly from two sources: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, both of which have regularly compiled national abortion data for approximately half a century, and which collect their data in different ways.

The CDC data that is highlighted in this post comes from the agency’s “abortion surveillance” reports, which have been published annually since 1974 (and which have included data from 1969). Its figures from 1973 through 1996 include data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and New York City – 52 “reporting areas” in all. Since 1997, the CDC’s totals have lacked data from some states (most notably California) for the years that those states did not report data to the agency. The four reporting areas that did not submit data to the CDC in 2021 – California, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey – accounted for approximately 25% of all legal induced abortions in the U.S. in 2020, according to Guttmacher’s data. Most states, though, do have data in the reports, and the figures for the vast majority of them came from each state’s central health agency, while for some states, the figures came from hospitals and other medical facilities.

Discussion of CDC abortion data involving women’s state of residence, marital status, race, ethnicity, age, abortion history and the number of previous live births excludes the low share of abortions where that information was not supplied. Read the methodology for the CDC’s latest abortion surveillance report , which includes data from 2021, for more details. Previous reports can be found at stacks.cdc.gov by entering “abortion surveillance” into the search box.

For the numbers of deaths caused by induced abortions in 1963 and 1965, this analysis looks at reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. In computing those figures, we excluded abortions listed in the report under the categories “spontaneous or unspecified” or as “other.” (“Spontaneous abortion” is another way of referring to miscarriages.)

Guttmacher data in this post comes from national surveys of abortion providers that Guttmacher has conducted 19 times since 1973. Guttmacher compiles its figures after contacting every known provider of abortions – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, and it provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond to its inquiries. (In 2020, the last year for which it has released data on the number of abortions in the U.S., it used estimates for 12% of abortions.) For most of the 2000s, Guttmacher has conducted these national surveys every three years, each time getting abortion data for the prior two years. For each interim year, Guttmacher has calculated estimates based on trends from its own figures and from other data.

The latest full summary of Guttmacher data came in the institute’s report titled “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2020.” It includes figures for 2020 and 2019 and estimates for 2018. The report includes a methods section.

In addition, this post uses data from StatPearls, an online health care resource, on complications from abortion.

An exact answer is hard to come by. The CDC and the Guttmacher Institute have each tried to measure this for around half a century, but they use different methods and publish different figures.

The last year for which the CDC reported a yearly national total for abortions is 2021. It found there were 625,978 abortions in the District of Columbia and the 46 states with available data that year, up from 597,355 in those states and D.C. in 2020. The corresponding figure for 2019 was 607,720.

The last year for which Guttmacher reported a yearly national total was 2020. It said there were 930,160 abortions that year in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with 916,460 in 2019.

- How the CDC gets its data: It compiles figures that are voluntarily reported by states’ central health agencies, including separate figures for New York City and the District of Columbia. Its latest totals do not include figures from California, Maryland, New Hampshire or New Jersey, which did not report data to the CDC. ( Read the methodology from the latest CDC report .)

- How Guttmacher gets its data: It compiles its figures after contacting every known abortion provider – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, then provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond. Guttmacher’s figures are higher than the CDC’s in part because they include data (and in some instances, estimates) from all 50 states. ( Read the institute’s latest full report and methodology .)

While the Guttmacher Institute supports abortion rights, its empirical data on abortions in the U.S. has been widely cited by groups and publications across the political spectrum, including by a number of those that disagree with its positions .

These estimates from Guttmacher and the CDC are results of multiyear efforts to collect data on abortion across the U.S. Last year, Guttmacher also began publishing less precise estimates every few months , based on a much smaller sample of providers.

The figures reported by these organizations include only legal induced abortions conducted by clinics, hospitals or physicians’ offices, or those that make use of abortion pills dispensed from certified facilities such as clinics or physicians’ offices. They do not account for the use of abortion pills that were obtained outside of clinical settings .

(Back to top)

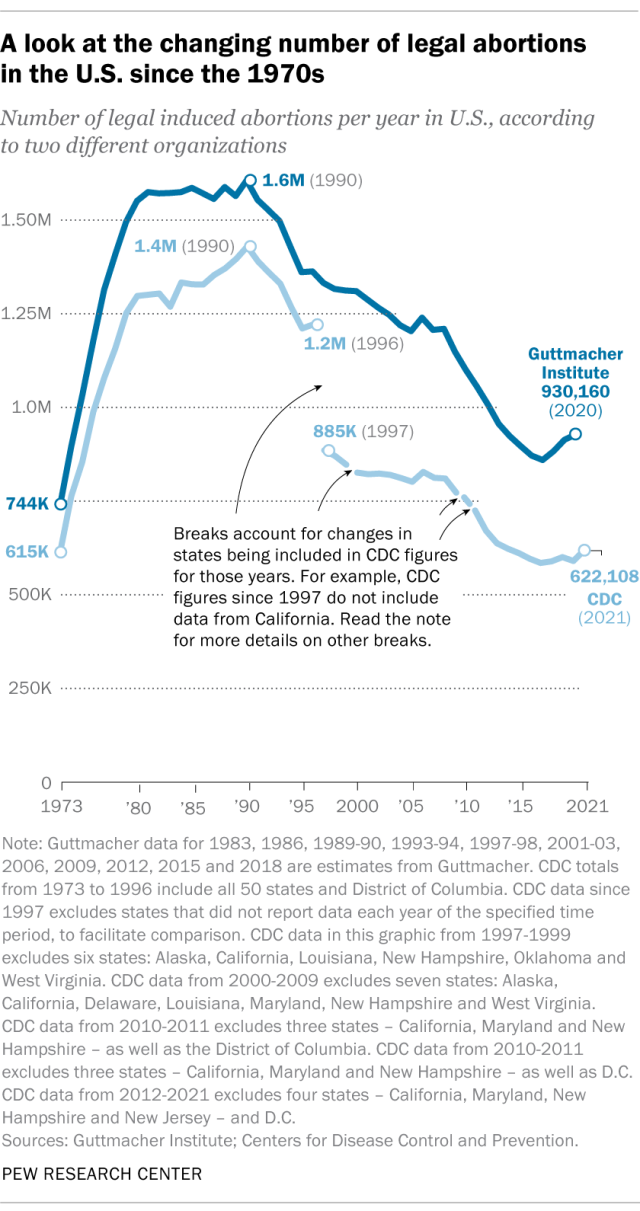

The annual number of U.S. abortions rose for years after Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure in 1973, reaching its highest levels around the late 1980s and early 1990s, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. Since then, abortions have generally decreased at what a CDC analysis called “a slow yet steady pace.”

Guttmacher says the number of abortions occurring in the U.S. in 2020 was 40% lower than it was in 1991. According to the CDC, the number was 36% lower in 2021 than in 1991, looking just at the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported both of those years.

(The corresponding line graph shows the long-term trend in the number of legal abortions reported by both organizations. To allow for consistent comparisons over time, the CDC figures in the chart have been adjusted to ensure that the same states are counted from one year to the next. Using that approach, the CDC figure for 2021 is 622,108 legal abortions.)

There have been occasional breaks in this long-term pattern of decline – during the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, and then again in the late 2010s. The CDC reported modest 1% and 2% increases in abortions in 2018 and 2019, and then, after a 2% decrease in 2020, a 5% increase in 2021. Guttmacher reported an 8% increase over the three-year period from 2017 to 2020.

As noted above, these figures do not include abortions that use pills obtained outside of clinical settings.

Guttmacher says that in 2020 there were 14.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. Its data shows that the rate of abortions among women has generally been declining in the U.S. since 1981, when it reported there were 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women in that age range.

The CDC says that in 2021, there were 11.6 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. (That figure excludes data from California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.) Like Guttmacher’s data, the CDC’s figures also suggest a general decline in the abortion rate over time. In 1980, when the CDC reported on all 50 states and D.C., it said there were 25 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44.

That said, both Guttmacher and the CDC say there were slight increases in the rate of abortions during the late 2010s and early 2020s. Guttmacher says the abortion rate per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 rose from 13.5 in 2017 to 14.4 in 2020. The CDC says it rose from 11.2 per 1,000 in 2017 to 11.4 in 2019, before falling back to 11.1 in 2020 and then rising again to 11.6 in 2021. (The CDC’s figures for those years exclude data from California, D.C., Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.)

The CDC broadly divides abortions into two categories: surgical abortions and medication abortions, which involve pills. Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved abortion pills in 2000, their use has increased over time as a share of abortions nationally, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher.

The majority of abortions in the U.S. now involve pills, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. The CDC says 56% of U.S. abortions in 2021 involved pills, up from 53% in 2020 and 44% in 2019. Its figures for 2021 include the District of Columbia and 44 states that provided this data; its figures for 2020 include D.C. and 44 states (though not all of the same states as in 2021), and its figures for 2019 include D.C. and 45 states.

Guttmacher, which measures this every three years, says 53% of U.S. abortions involved pills in 2020, up from 39% in 2017.

Two pills commonly used together for medication abortions are mifepristone, which, taken first, blocks hormones that support a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which then causes the uterus to empty. According to the FDA, medication abortions are safe until 10 weeks into pregnancy.

Surgical abortions conducted during the first trimester of pregnancy typically use a suction process, while the relatively few surgical abortions that occur during the second trimester of a pregnancy typically use a process called dilation and evacuation, according to the UCLA School of Medicine.

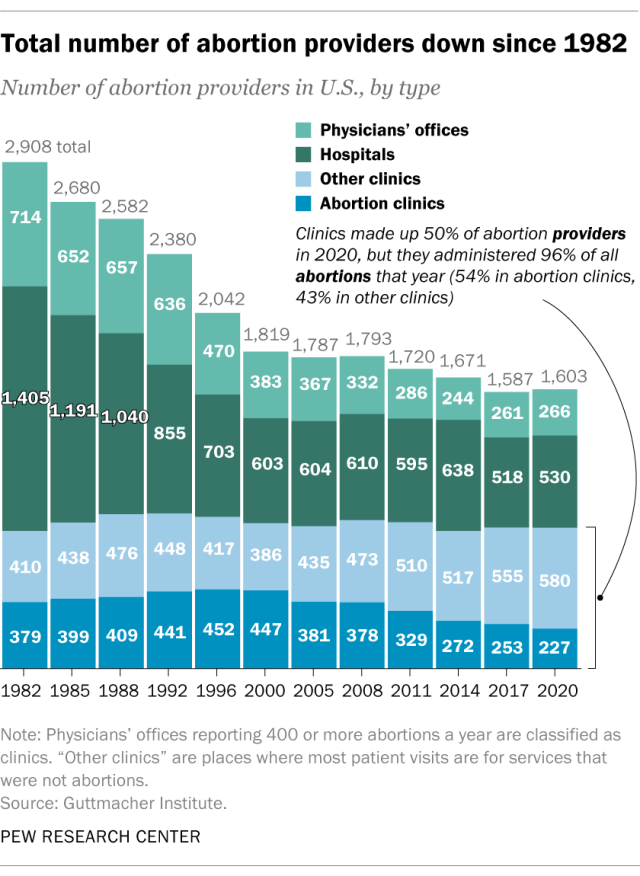

In 2020, there were 1,603 facilities in the U.S. that provided abortions, according to Guttmacher . This included 807 clinics, 530 hospitals and 266 physicians’ offices.

While clinics make up half of the facilities that provide abortions, they are the sites where the vast majority (96%) of abortions are administered, either through procedures or the distribution of pills, according to Guttmacher’s 2020 data. (This includes 54% of abortions that are administered at specialized abortion clinics and 43% at nonspecialized clinics.) Hospitals made up 33% of the facilities that provided abortions in 2020 but accounted for only 3% of abortions that year, while just 1% of abortions were conducted by physicians’ offices.

Looking just at clinics – that is, the total number of specialized abortion clinics and nonspecialized clinics in the U.S. – Guttmacher found the total virtually unchanged between 2017 (808 clinics) and 2020 (807 clinics). However, there were regional differences. In the Midwest, the number of clinics that provide abortions increased by 11% during those years, and in the West by 6%. The number of clinics decreased during those years by 9% in the Northeast and 3% in the South.

The total number of abortion providers has declined dramatically since the 1980s. In 1982, according to Guttmacher, there were 2,908 facilities providing abortions in the U.S., including 789 clinics, 1,405 hospitals and 714 physicians’ offices.

The CDC does not track the number of abortion providers.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that provided abortion and residency information to the CDC in 2021, 10.9% of all abortions were performed on women known to live outside the state where the abortion occurred – slightly higher than the percentage in 2020 (9.7%). That year, D.C. and 46 states (though not the same ones as in 2021) reported abortion and residency data. (The total number of abortions used in these calculations included figures for women with both known and unknown residential status.)

The share of reported abortions performed on women outside their state of residence was much higher before the 1973 Roe decision that stopped states from banning abortion. In 1972, 41% of all abortions in D.C. and the 20 states that provided this information to the CDC that year were performed on women outside their state of residence. In 1973, the corresponding figure was 21% in the District of Columbia and the 41 states that provided this information, and in 1974 it was 11% in D.C. and the 43 states that provided data.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported age data to the CDC in 2021, the majority of women who had abortions (57%) were in their 20s, while about three-in-ten (31%) were in their 30s. Teens ages 13 to 19 accounted for 8% of those who had abortions, while women ages 40 to 44 accounted for about 4%.

The vast majority of women who had abortions in 2021 were unmarried (87%), while married women accounted for 13%, according to the CDC , which had data on this from 37 states.

In the District of Columbia, New York City (but not the rest of New York) and the 31 states that reported racial and ethnic data on abortion to the CDC , 42% of all women who had abortions in 2021 were non-Hispanic Black, while 30% were non-Hispanic White, 22% were Hispanic and 6% were of other races.

Looking at abortion rates among those ages 15 to 44, there were 28.6 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic Black women in 2021; 12.3 abortions per 1,000 Hispanic women; 6.4 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic White women; and 9.2 abortions per 1,000 women of other races, the CDC reported from those same 31 states, D.C. and New York City.

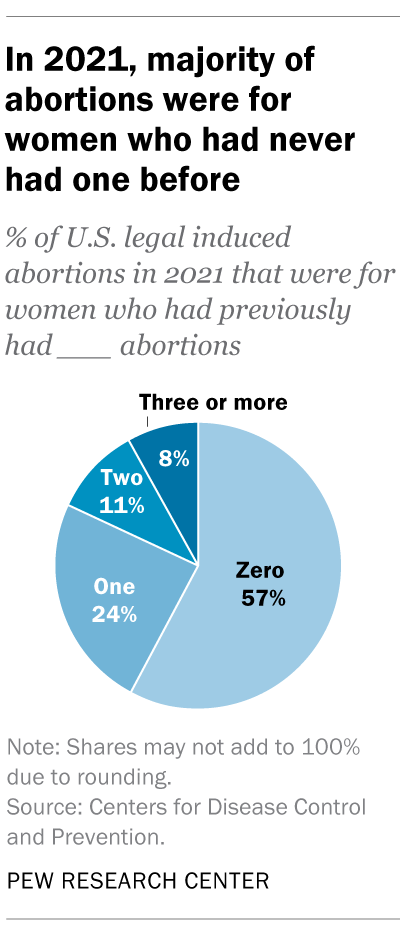

For 57% of U.S. women who had induced abortions in 2021, it was the first time they had ever had one, according to the CDC. For nearly a quarter (24%), it was their second abortion. For 11% of women who had an abortion that year, it was their third, and for 8% it was their fourth or more. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

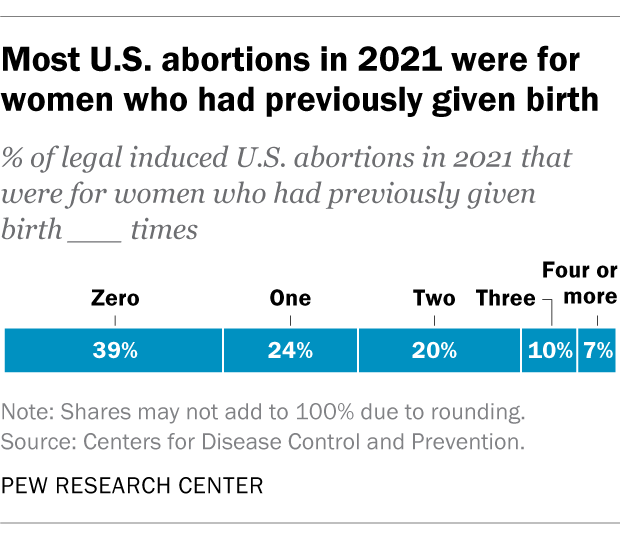

Nearly four-in-ten women who had abortions in 2021 (39%) had no previous live births at the time they had an abortion, according to the CDC . Almost a quarter (24%) of women who had abortions in 2021 had one previous live birth, 20% had two previous live births, 10% had three, and 7% had four or more previous live births. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

The vast majority of abortions occur during the first trimester of a pregnancy. In 2021, 93% of abortions occurred during the first trimester – that is, at or before 13 weeks of gestation, according to the CDC . An additional 6% occurred between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, and about 1% were performed at 21 weeks or more of gestation. These CDC figures include data from 40 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

About 2% of all abortions in the U.S. involve some type of complication for the woman , according to an article in StatPearls, an online health care resource. “Most complications are considered minor such as pain, bleeding, infection and post-anesthesia complications,” according to the article.

The CDC calculates case-fatality rates for women from induced abortions – that is, how many women die from abortion-related complications, for every 100,000 legal abortions that occur in the U.S . The rate was lowest during the most recent period examined by the agency (2013 to 2020), when there were 0.45 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. The case-fatality rate reported by the CDC was highest during the first period examined by the agency (1973 to 1977), when it was 2.09 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. During the five-year periods in between, the figure ranged from 0.52 (from 1993 to 1997) to 0.78 (from 1978 to 1982).

The CDC calculates death rates by five-year and seven-year periods because of year-to-year fluctuation in the numbers and due to the relatively low number of women who die from legal induced abortions.

In 2020, the last year for which the CDC has information , six women in the U.S. died due to complications from induced abortions. Four women died in this way in 2019, two in 2018, and three in 2017. (These deaths all followed legal abortions.) Since 1990, the annual number of deaths among women due to legal induced abortion has ranged from two to 12.

The annual number of reported deaths from induced abortions (legal and illegal) tended to be higher in the 1980s, when it ranged from nine to 16, and from 1972 to 1979, when it ranged from 13 to 63. One driver of the decline was the drop in deaths from illegal abortions. There were 39 deaths from illegal abortions in 1972, the last full year before Roe v. Wade. The total fell to 19 in 1973 and to single digits or zero every year after that. (The number of deaths from legal abortions has also declined since then, though with some slight variation over time.)

The number of deaths from induced abortions was considerably higher in the 1960s than afterward. For instance, there were 119 deaths from induced abortions in 1963 and 99 in 1965 , according to reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. The CDC is a division of Health and Human Services.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published May 27, 2022, and first updated June 24, 2022.

Jeff Diamant is a senior writer/editor focusing on religion at Pew Research Center .

Besheer Mohamed is a senior researcher focusing on religion at Pew Research Center .

Rebecca Leppert is a copy editor at Pew Research Center .

Cultural Issues and the 2024 Election

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many places, especially in europe, public opinion on abortion, americans overwhelmingly say access to ivf is a good thing, broad public support for legal abortion persists 2 years after dobbs, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Gender linked fate explains lower legal abortion support among white married women

Leah ruppanner, gosia mikołajczak, kelsy kretschmer, christopher t stout.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2019 Mar 18; Accepted 2019 Sep 17; Collection date 2019.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abortion is uniquely connected to women’s experiences yet women’s attitudes towards legal abortion vary across the pro-choice/anti-abortion spectrum. Existing research has focused on sociodemographic characteristics to explain women’s levels of abortion support. Here, we argue that abortion attitudes vary with women’s perceptions of gender linked fate, or the extent to which some women see their fates as tied to other women. Drawing upon existing research showing that married white women report lower levels of gender linked fate than their non-married counterparts, we assess these relationships for abortion attitudes applying the 2012 American National Election Survey ( n = 2,173). Using mediation analysis, we show that lower levels of gender linked fate among married white women (vs. non-married white women) explain their stronger opposition to abortion. As many state governments are increasingly legislating restricted access to legal abortion, understanding factors explaining opposition to legal abortion is urgently important.

On May 16, 2019, Alabama’s state governor signed the most restrictive abortion law to date, outlawing virtually all abortions (with risk to pregnant woman’s life being the only admissible exception) and altering penal sanctions such that medical doctors who perform abortions risk up to 99 years in prison. Five other U.S. states–Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, Mississippi and Ohio–have also legislated heartbeat bills, or a ban of any abortion once a heartbeat of a fetus can be detected (i.e., 6 to 8 weeks after conception). The passage of these bills aims to push abortion legislation to the Supreme Court to overturn legal precedent. Legal abortion has historically been one of the most divisive political issues in American politics but the stakes for abortion access are amplified in the current political environment.

Abortion is often used as a litmus test for dividing conservative from liberal perspectives. Since 1973, when the Supreme Court legalized abortion across the United States with its Roe v . Wade decision, the issue has only grown in importance, as activists, doctors, and politicians have struggled over proposed and enacted state restrictions to abortion services. The political and moral debates around women’s access to safe and legal abortion have informed a broad research agenda seeking to understand the demographics of American opinion on reproductive rights, and abortion specifically. Here, we show that weaker perceptions of gender linked fate among married white women (compared to nonmarried white women) play a crucial role in explaining abortion attitudes.

Following Roe v . Wade , researchers were primarily interested in understanding cleavages in legal abortion support by race and education, with a surge in research in the 1980s (see e.g., [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]). The results showed strong racial differences, with white women supporting legal abortion at higher rates than black women, even though the latter were three times more likely on average to have an abortion [ 1 , 3 , 7 , 8 ]. Since the 1980s, however, racial gaps in support for legal abortion have narrowed, while other demographic determinants are growing in influence [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. College-educated women are historically more likely to support legal abortion [ 1 , 12 – 15 ]. Those with higher incomes are also more likely to support legal abortion, underscoring that abortion support, along with other progressive attitudes, is tied to higher earnings [ 1 , 4 , 16 , 17 ].

Conversely, religiosity is an important determinant of opposition to abortion, serving as a strong voting block issue. Evangelical Protestants are the most likely to oppose abortion, and are among the strongest advocates for legislation to nullify Roe v . Wade [ 4 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Similarly, recent research documents that constituents of Southern states are comprehensively less supportive of abortion than those in the Northern states [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The Southern states exhibit intense concentrations of conservative religiosity, and for many lawmakers hailing from the South, anti-abortion attitudes serve as important evidence of their moral conservatism [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Thus, it is no surprise that the Southern states–Missouri, Georgia, Kentucky and Mississippi–clustered in their passage of restrictive abortion laws in 2019 [ 30 ]. Here, we show that perceptions of gender linked fate–or seeing one’s future as linked to other women–helps explain support for legal abortion, extending existing research linking gender linked fate to conservative political attitudes [ 31 ].

Complicating this research, however, is the apparent lack of a gender effect for abortion support. As noted by Hout [ 32 ], women are more likely than men to occupy both extremes (pro-choice and anti-abortion) on the abortion spectrum. Although abortion is intrinsically tied to women’s bodies, past research has generally found that women are no more likely to support legal abortion than men, despite the fact that restricting abortion access disproportionately affects women [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. The absence of gender differences has led some researchers to conclude that gender matters less than religious, educational and racial differences [ 36 ]. A substantial body of research has attempted to explain why women fail to support legal abortion at higher rates than men, with many attributing it to women’s reticence towards undergoing an abortion themselves, as well as how these attitudes vary based on circumstances that lead women to seek an abortion (for a review, see [ 36 ]). While others have focused on the Rossi Scale as a measure of abortion support, we use a single item measure of abortion support which identifies the intensity of support rather than variance in support by specific condition, which may not be ordinal or continuous [ 37 ]. In this regard, abortion is often understood from an individualized lens but may also capture variation in perceptions of a woman’s connection to other women. Here, we contribute to this conversation by assessing how differences in perceptions of gender linked fate explain differences in women’s abortion attitudes, depending on their marital status.

Gender linked fate measures the extent to which women perceive their futures to be tied to those of other women [ 38 ]. Individuals high in gender linked fate perceive their future resources and experiences to be tied to those who share the same gender. In the case of abortion, women’s futures are truly linked–regardless of one’s own likelihood of having an abortion, voting to reduce access to legal abortion will inherently affect the future lives of other women. Emerging research shows that gender linked fate varies by race and marital status with married white and Latina women reporting lower levels of gender linked fate than their non-married counterparts and, as a consequence, voting more conservatively [ 31 ]. These patterns may extend to abortion attitudes as well with weaker gender linked fate explaining lower support for legal abortion. We note here that our analyses do not replace other mechanisms that structure abortion attitudes–education, income, regionality, ideology and religion–but rather offer an additional theoretical mechanism to explain differences in women’s abortion attitudes.

As indicated above, we anticipate that the relationship between gender linked fate and abortion attitudes will vary by race. White and Latina conservative women are typically the most vocal opponents of abortion [ 19 , 39 ] and white women and Latina women report lower levels of gender linked fate than black women [ 31 ]. Black women’s reproductive decisions are structured around a shared perception of racial inequity, structural inequality, poor life-chances, high rates of poverty and exposure to violence [ 40 ]. These factors tend to shape the African American community’s sense of ‘linked fate’ including their support for legal abortion [ 17 , 38 , 41 ]. Among black women, marital status is less important than race in binding women together along perceptions of gender linked fate [ 31 ]. As a consequence, black women may report higher levels of gender linked fate and support for legal abortion across all racial groups and marital statuses. In addition, black women’s support of legal abortion is net of their higher religiosity suggesting abortion attitudes are more complex than simple racial, marital or religious divides, tapping into the intersection of these identities. We explore these gaps paying careful attention to race and marital status and differences in gender linked fate.

We test our assumptions by utilizing nationally representative data from the 2012 American National Election Survey (ANES; n = 2,173) that measured gender linked fate, legal abortion support, marital status, and race. By employing mediation analysis, we identify both the direct and indirect impact of marital status on attitudes towards legal abortion. Specifically, we show that, among white women, differences in gender linked fate by marital status explain opposition to legal abortion net of other sociodemographic controls. These results are politically and socially important, given that white women are an increasingly influential demographic in American politics and the most conservative on abortion [ 39 , 42 ]. Our results are especially relevant for restrictive abortion laws in states like Georgia and Alabama which have some of the highest concentrations of married white women in the nation [ 43 ]. Thus, the demographic concentration of married white female voters in certain states may help explain shifts in the political climate on hot-button issues like abortion, with gender linked fate an important explanatory mechanism to understand this changing political landscape.

Group consciousness and gender linked fate

Existing research has largely focused on gender group consciousness but less is known about what structures perceptions of gender linked fate [ 44 ]. Group consciousness and gender linked fate, although interrelated, are distinct theoretical concepts [ 45 , 46 ]. Group consciousness measures a person’s internalized group identity, along with their political awareness of their own gender, racial or class group’s position in society [ 44 ]. Linked fate captures the perception that an individual’s life chances are intrinsically tied to those who belong to the same demographic group. Strong group consciousness is often a precursor to developing a sense of linked fate but individuals can have group consciousness without linked fate [ 45 , 47 ]. For example, a woman may see women as a subjugated group in society but may not see her personal life chances as tied to other women (i.e. group consciousness but no gender linked fate). Thus, those with a high level of group consciousness do not necessarily perceive their fate as linked to others in their demographic group [ 45 ]. Moreover, Sanchez and Vargas [ 46 ] demonstrate that group consciousness and linked fate have different consequences for behaviors across racial groups. Thus, we would expect that gender group consciousness may shape attitudes differently than gender linked fate with important between-group differences.

Since abortion is an issue that specifically affects women, gender linked fate may be an important mechanism to explain legal abortion support. To date, no study has established this link, an omission that likely reflects a dearth in data on gender linked fate as it is rarely included in large scale representative surveys. This omission is surprising given that racial linked fate is consistently shown to structure political attitudes and voting [ 38 , 46 , 47 ]. Fortunately, the 2012 American National Election Survey included gender linked as a one-off survey item asked of a representative sample of female voters, which allowed us to investigate the connection between gender linked fate and legal abortion attitudes in a large and representative group of women by marital status and race. In our methodological approach, we follow existing research of Stout, Kretschmer and Ruppanner [ 31 ] that used the 2012 ANES to show married white and Latina women report lower levels of gender linked fate than their non-married counterparts which helped explain their more conservative political attitudes. Using an equivalent methodological approach, we extend these relationships to support for legal abortion.

The role of marriage and shifting perceptions of gender linked fate

Marriage is shown to alter women’s perceptions of the world that in turn shift their political and social attitudes, as described in detail previously [ 31 ]. Longitudinal analyses document that women become more conservative on gender-related issues and view themselves as having less in common with other women following marriage [ 48 , 49 ]. For many women, marriage financially ties them to their husbands, and, by extension, they come to view changes in men’s economic and social standing as a threat to the family’s finances [ 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ]. These experiences are counter to those of unmarried women who are more likely to be in poverty and work in insecure jobs [ 55 ]. As a result, unmarried women see their futures as more tightly linked to other women [ 31 ], in part, due to greater economic instability [ 56 , 57 ]. Bolzendahl and Meyers [ 57 ] show that single women are more supportive of feminist issues than married women, with stronger effects among women who are more reliant on their own income. Married women, by contrast, are very unlikely to be sole breadwinners in their households [ 56 ] and, as a consequence, unlikely to see their futures as tied more explicitly to those of other women.

Marriage also traditionalizes domestic gender relations, with married women assuming a larger share of the housework even when their earnings exceed those of their husbands’ [ 58 , 59 ]. Women who find themselves relying on their husbands’ income, tend to become less concerned about gender discrimination more broadly [ 60 , 61 ]. Indeed, marriage appears to lessen women’s sense of ‘belonging’ to the broader female community, which is exhibited, in part, through married women’s lower support for policies to mitigate gender discrimination [ 60 , 61 ]. Married women are also more likely to view changes in women’s social standing as coming at the expense of men’s social and economic status, and consequently, many view feminist politics as threatening to their own well-being because their husbands are threatened [ 62 ]. Collectively, these factors have been found to have a conservatizing effect, making married women less likely overall to support abortion rights [ 21 ].

Yet, absent from these discussions are the ways differing levels of gender linked fate among women with different marital status may condition these relationships. Since abortion is a procedure performed on women (and trans men) and thus is intrinsically connected to the futures of other women (and trans men), the traditionalizing effect of marriage on gender linked fate may be particularly pernicious for abortion support. Understanding the linkages between marital status and gender linked fate ought to provide a clearer picture of the conditions under which different women support legal abortion.

Race, abortion and gender linked fate

Past research in the U.S. shows that gender linked fate varies across racial and ethnic lines with black women reporting the highest levels of gender consciousness and gender linked fate followed by Latinas, whites and Asian-Americans [ 31 , 63 , 64 ].

Further, existing research shows the relationship between marital status and gender linked fate is significant for white and Latina women, but not for black women [ 31 ]. For married white and Latina women, economic dependence on husbands tends to suppress perceptions of gender linked fate, but black women are more likely than women in other racial groups to be the primary breadwinner in their families [ 65 ]. Black women’s historical position as breadwinners makes them uniquely positioned to see their fate as tied to other women as black women’s experiences with both racial and gender inequality allow them to identify intersecting matrices of oppression and discrimination [ 45 , 66 ]. This increases their capacity to empathize with other marginalized groups and to more closely identify with feminist political attitudes [ 67 ].

As described in detail previously [ 31 ] Latinas are more likely than other groups of women to have traditional breadwinner-homemaker divisions of labor, reinforcing wives’ financial dependence on their husbands [ 68 , 69 ]. Latina women report spending the largest time in housework relative to black and white women and have the lowest rate of female breadwinners compared to all other racial groups, which may weaken their perceptions of gender linked fate [ 69 , 70 ]. Latinas’ migration patterns may also weaken perceptions of gender linked fate, as many Latinas are first- and second-generation migrants who maintain the culture of their country of origin [ 71 ]. This includes strong support for “familism,” or the idea that the interests of the family as a whole take precedence over the interest of any single member of the family [ 68 ]. Since married Latina women are likely to be in breadwinning/homemaking families, support for familism likely shifts alliances to their husbands, thus weakening their perceptions of gender linked fate. Further, Latinos are more likely to be religious, and Protestant Latinos have been found to have particularly negative attitudes towards abortion [ 18 , 19 ].

Summary of expectations

Based on previous research, we expect women with lower levels of gender linked fate to report less support for legal abortion than women who see their fates as tied to other women. We expect these relationships to vary by race and marital status, consistent with previous research. Specifically, we expect married white and Latina women to report lower levels of abortion support than their non-married counterparts, in part, because of their lower levels of gender linked fate [ 31 ]. Our formal hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 1 : Women with lower gender linked fate will report weaker support for legal abortion. Hypothesis 2 : Marital status will be linked to legal abortion attitudes among white and Latina women but not black women. Hypothesis 3 : Lower support for legal abortion among married white and Latina women will be, at least partially, explained by weaker perceptions of gender linked fate.

Data, measures and methods

We employed the 2012 American National Election Study (ANES) which provides a nationally representative survey of American attitudes on abortion and gender linked fate. The American National Election Survey is collected biennially to measure American’s political attitudes, voting preferences and demographics. The 2012 ANES is, to our knowledge, the only survey year in which gender linked fate was included in the survey instrument. Thus, we utilized the most up-to-date nationally representative data on this topic. We first tested for a gender gap in abortion attitudes, pooling the sample of men and women. Then, we restricted the sample to women because gender linked fate questions were presented exclusively to female respondents. This allowed us to determine whether gender linked fate helped explain abortion attitudes among women. The relatively large sample sizes provided by ANES also allowed us to estimate differences by race and marital status. Although we had adequate sample sizes for each racial group to estimate differences by marital status, we acknowledge that the number of white women in the sample is substantially larger than the numbers of black and Latina women, respectively.

For models assessing the gender gap in abortion support, our effective sample size was 2,235 men and 2,225 women (see S1 Table ) Since gender linked fate was only asked of women, our effective sample was s 2,173 women who provided responses to the questions of interest (see S2 Table ).

Abortion attitudes

Legal abortion attitudes served as our key dependent variable. We measured legal abortion support through a self-reported agreement with the following statement: “Do you favor, oppose, or neither favor nor oppose abortion being legal if the woman chooses to have one?”. Responses were measured on a 9-point scale ranging from (1) favor a great deal to (9) oppose a great deal. We reverse coded abortion attitudes so that higher values indicate greater support for legal abortion.

Key independent variables: Gender, gender linked fate, marital status and race

Initially, gender was used as a key explanatory factor to measure whether a gender gap in legal abortion support was evident in our sample. Those who self-identified as a man (value = 0) served as our reference group. Then, gender linked fate was used as a key mediator variable for a subsample of female respondents. Women were asked to report their levels of gender linked fate through a two-step process. First, they were asked: “Do you think that what happens generally to women in this country will have something to do with what happens in your life?”. If the respondent agreed to this question, they were then asked the following: “How much does what happens to others affect you?” Responses to this second question were measured on a three-point scale: (1) “a little”; (2) “some”; and (3) “a lot”. Higher values reflected stronger perceptions of gender linked fate.

We used these questions to construct a four-point gender linked fate measure. Respondents who answered “no” to the first question were given a score of 1, those who answered “a little” to the second question were given a score of 2, those who answered “some”–a score of 3, and those who answered “a lot” a score of 4. Our measure was consistent with the past measurement of linked fate for other groups (see [ 38 , 64 , 72 , 73 ], and gender specifically [ 31 ].

Existing research shows gender linked fate varies by marital status and race [ 31 ]. We expected these differences to structure legal abortion support as well. To assess these hypotheses, we included measures of marital status and race. We compared single (i.e., never married) and divorced/separated women to their married counterparts. Women who stated that they were cohabiting with their partners (n = 134) were removed from the analysis. We excluded widows given their relatively small sample sizes across all racial groups (n = 176, n = 61 and n = 25 among white, black, and Latina women, respectively). We included self-reported race and compared white women to black and Latina women. The ANES does not have adequate sampling of Asian and bi-racial women and thus these women were excluded from our sample.

Attitudinal, political and sociodemographic controls

To isolate the effect of gender linked fate on legal abortion support, we included a range of potential confounders. Income and education have been consistently shown to be an important predictor of abortion support with more affluent and educated Americans more supportive of legal abortion. Thus, we included measures of the total household income and the amount of completed education in the model. Older Americans hold more conservative views on gender and politics and thus we included a measure of age in our models. We also controlled for having a child (eighteen years old or younger) at home, religiosity (measured by the frequency of church attendance on a scale from 1 –every week to 5 –never), political ideology (measured on a scale from 1 –extremely liberal to 7 –extremely conservative), and employment status (recoded as 1 –employed, 0 –other). Other’ included student, homemaker, retired, disabled, unemployed. Additional analyses with ‘homemaker’ as a separate category showed a similar pattern of results. We also investigated feminist attitudes as an alternative explanation for the tested link. Feminist attitudes were approximated by the following items: support for traditional gender roles (1 –better if man works and woman takes care of home, 2 –no difference, 3 –worse if man works and a woman takes care of the home), perceptions of gender discrimination (1 –not a problem; 5 –an extremely serious problem), and a feminist feeling thermometer (0–100). See S6 and S7 Tables for a summary of the results.

Analytical approach

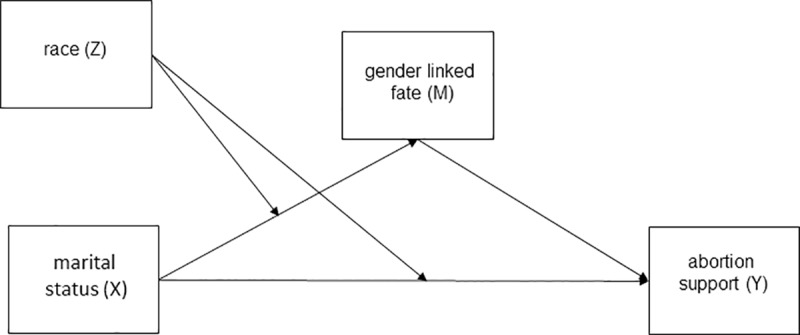

All analyses were computed using R (version 3.6.0, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Ordinal logistic regressions were calculated using package ordinal . Marginal means for gender linked fate and abortion support were calculated and plotted using package emmeans [ 74 ]. Mediation effects were calculated using natural effect models [ 75 ] included in package medflex [ 76 ], which allowed us to test a mediation model with an ordinal mediator, and to obtain estimates of indirect and direct effects of marital status conditional on race ( Fig 1 shows a visual overview of our model).

Fig 1. Moderated mediation model tested in the study.

The model was estimated with ‘married’ as a reference group.

Table 1 shows the results of a linear regression predicting legal abortion support among men and women, net of sociodemographic controls. Contrary to previous studies, our analysis revealed that respondent’s gender had a significant effect on support for legal abortion when controlling for other sociodemographic covariates.

Table 1. Linear regression predicting legal abortion support among men and women.

N = 3,785 (675 observations were deleted due to missing data); CI–Confidence Intervals.

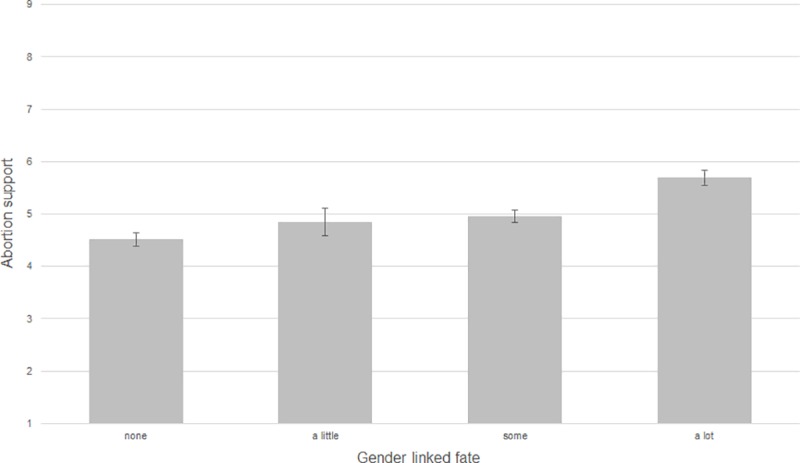

Next, we assessed the relationship between gender linked fate and abortion attitudes for women. Fig 2 provides a visual overview of the relationship between gender linked fate and support for abortion. Our first hypothesis predicted that women with lower levels of gender linked fate would report weaker support for abortion. Fig 2 confirms this expectation–women who viewed their futures as less tied to other women did report weaker support for abortion (rτ = 0.10, p < 0.001).

Fig 2. Gender linked fate and legal abortion support.

Source: 2012 American National Election Study. rτ = 0.10, p < 0.001.

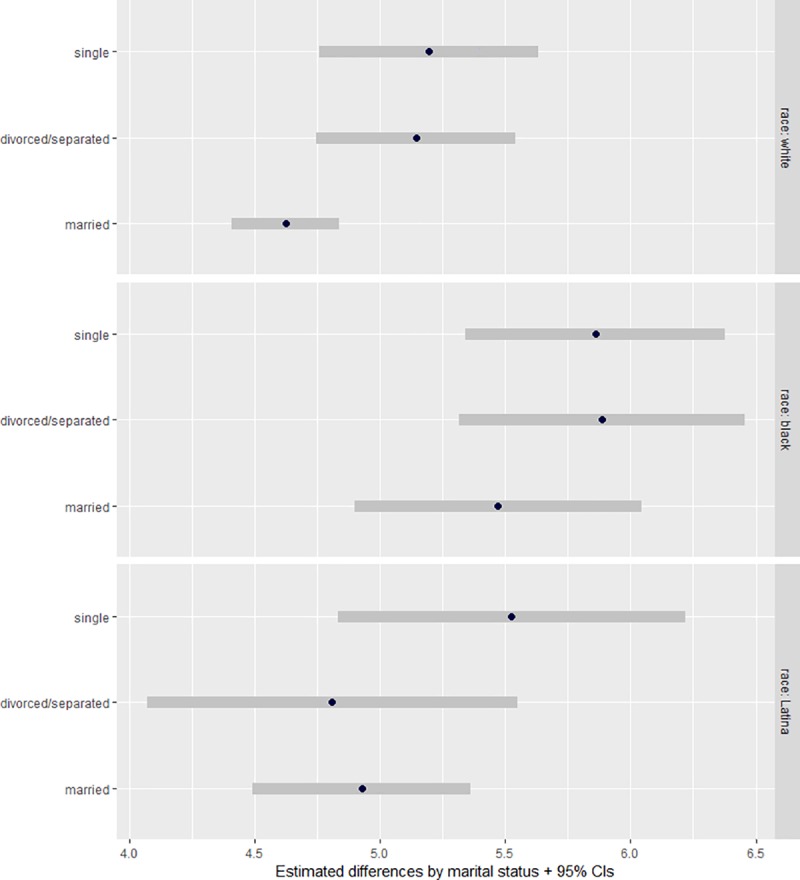

Guided by previous research, we expected that marital status would be linked to legal abortion support among white and Latina women, but not among black women. Results presented in Fig 3 lend partial support for this claim (detailed results can be found in S3 and S4 Tables). White married women were less supportive of abortion than their single or divorced counterparts. By contrast, black and Latina women’s level of abortion support did not differ by marital status, countering our expectations that Latina women’s gender linked fate would be structured similarly to white women’s.

Fig 3. Predicted levels of legal abortion support by marital status and racial/ethnic group.

Source: 2012 American National Election Study. CI = Confidence Interval. white: n = 221 single, n = 237 divorced/separated, n = 881 married; black: n = 189 single, n = 140 divorced/separated, n = 132 married; Latina: n = 94 single, n = 78 divorced/separated; n = 201 married. Effects were adjusted for age, income, employment status, education, having children (eighteen or younger) at home, religiosity (frequency of church attendance) and political ideology.

Finally, we expected that the difference in abortion support by marital status for white and Latina women would be explained by their lower levels of gender linked fate. Table 2 explores these relationships and lends partial support for this hypothesis (full details of the analysis can be found in S3 – S6 Tables). Married white women’s lower levels of gender linked fate, relative to single white women, explained 16.3% of the relationship between marriage and abortion attitudes. A similar relationship was found when comparing married white women to their divorced/separated counterparts. Lower levels of gender linked fate among married white women, compared to divorced/separated white women, explained 14.5% of the effect of marriage on abortion. The relationships between gender linked fate, marriage and abortion support were significant only among white women indicating that marriage plays a distinct role in gender linked fate attitudes for this group.

Table 2. Mediation analysis predicting legal abortion support via gender linked fate.

* p <0.05, ** p <0.01; 95%CI–bootstrap percentile confidence intervals based on 1,000 bootstrap samples; Effects were adjusted for age, income, employment status, education, having children (eighteen or younger) at home, religiosity (frequency of church attendance) and political ideology.

Additionally, we conducted several sensitivity analyses to confirm that the observed link between marital status and abortion attitudes is attributable to gender linked fate, not feminist attitudes (see S8 Table ). None of the alternative mediators considered in the analysis explained a significant proportion of variance. Additionally, we tested whether the observed relationships might vary with the respondent’s age and employment status (see S9 – S11 Tables). The analysis indicated that, among white respondents, marital status had a stronger effect on gender linked fate among younger respondents (<45) but did not vary with employment status. A similar age trend could be observed for black and Latina respondents. However, these results were not significant and should be treated with caution due to small numbers, particularly of young (<45) divorced/separated women. For similar reasons, the results of the moderated mediation analysis presented in S1 Table should be also only considered as tentative.

Abortion is an increasingly important political issue in the United States. The recent passage of an abortion ban in Alabama and abortion restrictions in other states are a clear indication that legal abortion is an increasingly important political issue with serious implications for women. Here, we investigate how gender linked fate, or the perception that a woman’s future is intrinsically tied to other women, is associated with support for abortion. Because abortion is intrinsically tied to women’s bodies, perceptions of gender linked fate are an important explanatory mechanism. Research on public attitudes has consistently found stark divides in support for abortion across religiousness, race, region, and political ideology [ 1 , 3 , 7 , 8 ]. Yet, the link to gender linked fate by race and marital status is conspicuously absent–this study fills that void. Our study is important as women, especially white married women, are playing an increasingly critical role in American politics, demonstrated by the fracture of suburban white women from the Republican party and its impact on the 2018 midterm election. Women make up the majority of the population, have high voting participation rates, and, on average tend to vote in more liberal ways [ 77 ]. Given the increasing salience of abortion in every level of politics and the rising influence of women, investigation of drivers of abortion attitudes among women deserves greater attention. Here, we untangled one underlying explanation of women’s attitudes toward legal abortion by paying attention to differences in gender linked fate by marital status.

We find that women are, on average more supportive of abortion than men, a finding that counters previous research that fails to document a gender gap [ 33 – 36 ]. We then find that women with weaker perceptions of gender linked fate report lower levels of legal abortion support. This relationship is meaningful for academics to understand gender linked fate as an explanatory mechanism of attitudes, and politicians and advocacy groups to develop more effective political messaging. Here, we show that among the female population, gender linked fate is an important precursor for abortion support. As a consequence, shifting perceptions of gender linked fate may impact attitudes towards legal abortion.

After first identifying this generalized trend, we then identify racial patterns of legal abortion support by marital status. As predicted, white married women report lower levels of legal abortion support than their single counterparts. By contrast, black and Latina women reported equivalent levels of legal abortion support across marital statuses. Our results indicate that marriage plays a distinct role in structuring legal abortion attitudes for white women. This finding is, perhaps, not surprising in light of the literature on racial linked fate whereby people of color see their futures as more intrinsically linked compared to white respondents [ 38 , 45 , 47 , 66 ]. Existing scholarship shows black women are uniquely positioned to identify compounding matrices of oppression by race and gender, seeing their futures as more tightly linked to blacks and other women [ 45 , 66 ]. These identities appear to extend to abortion attitudes as well in that, for women of color, marriage does not lower support for legal abortion nor do their lower levels of gender linked fate explain the relationship between marriage and legal abortion attitudes. Again, this appears to be a relationship distinct from white women’s experiences.

Our findings parallel existing scholarship that shows marriage is traditionalizing [ 48 , 49 ] and emerging literature that identifies an underlying causal mechanism–gender linked fate [ 31 ]. In this regard, marriage appears to have a particular traditionalizing impact for white women that is not evident for other racial groups identifying an interesting pathway for future longitudinal research.

Notably, we estimate these relationships net of a range of sociodemographic controls including income, education, and employment status. We also compare alternative explanations of the observed link looking at different proxies of feminist attitudes. Our results indicate that gender linked fate is a robust and theoretically distinct concept that structures married white women’s attitudes.

Limitations and future directions

The 2012 ANES had several limitations in regards to our study. First, the gender linked fate question was only presented to female, not male respondents. Although, as we have argued, abortion has a unique meaning for women to the extent that it is intrinsically tied to their bodies, we cannot exclude that men’s level of connection to other women (or to other men) could explain their support or opposition to legal abortion. This points to a data gap that could be explored in subsequent studies. Another limitation is that, while ANES provides sufficient numbers of women by race (for white, black and Latina respondents), and marital status (for married, divorced/separated and single women) to allow for comparisons, the majority of the sample is white. It is feasible that a larger sample including more black and Latina women may have captured marriage status differences in gender linked fate and abortion attitudes across these groups. Future studies should test whether the unique effect we find for white women can be observed in other minorities. Finally, given that the focus of ANES is on political attitudes more broadly, the questionnaire did not include other possible moderators of abortion attitudes and gender linked fate, such as access to contraception or length of marriage.

We believe that our study provides a promising avenue for future research, including longitudinal designs which would allow for testing whether marriage traditionalizes attitudes or whether more traditional men and women are more likely to marry, and to uncover a “dose-effect” of marriage, that is the extent to which duration of marriage structures perceptions of gender linked fate and abortion attitudes. Experimental methods could further shed light on the causal relationship between marriage, gender linked fate and abortion attitudes. Future studies could also explore how contraception use and past abortion experiences structure abortion support. Finally, future studies could also aim to uncover the link between gender linked fate and group consciousness paying careful attention to men as well as women.

Our results from a nationally-representative sample of American women indicate that abortion attitudes, similar to general political conservativism, vary by marital status and perceptions of gender linked fate. Crucially, we show that married white women see their futures and fates as less tied to other women than non-married white women and, as a consequence, are less supportive of legal abortion. These findings are important in the context of changing political alliances in the post-Trump era whereby many suburban educated white women split from the Republican party in the 2018 midterms. Whether this fissure is temporary or long-lasting is an empirical question that cannot yet be answered, but our results suggest that abortion support, like general political conservatism, depends on race, marital status and perceptions of gender linked fate. The passage of restrictive abortion laws in many states with high concentrations of white married women suggests a need to refine this area of inquiry and further exploration of the underlying mechanisms of abortion attitudes.

Supporting information

Data availability.

Data are publicly available at the American National Election Studies website: https://electionstudies.org/data-center/ .

Funding Statement

We received money from the University of Melbourne Chancellery of Research and Enterprise, 3012 to LR. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

- 1. Combs MW, Welch S. Blacks, whites, and attitudes toward abortion. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1982. January 1;46[4]:510–20. 10.1086/268748 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Granberg D, Granberg BW. Abortion attitudes, 1965–1980: Trends and determinants. Family Planning Perspectives. 1980. September 1;12[5]:250–61. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Hall EJ, Ferree MM. Race differences in abortion attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1986. January 1;50[2]:193–207. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Legge JS Jr. The determinants of attitudes toward abortion in the American electorate. Western Political Quarterly. 1983. September;36[3]:479–90. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Secret PE. The impact of region on racial differences in attitudes toward legal abortion. Journal of Black Studies. 1987. March;17[3]:347–69. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Scott J. Conflicting beliefs about abortion: legal approval and moral doubts. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1989. December [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Dugger K. Race differences in the determinants of support for legalized abortion. Social Science Quarterly. 1991. September. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Lynxwiler J, Gay D. Reconsidering race differences in abortion attitudes. Social Science Quarterly. 1994. March. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Lynxwiler DG. The impact of religiosity on race variations in abortion attitudes. Sociological Spectrum. 1999. June 1;19[3]:359–77. 10.1080/027321799280190 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Wilcox C. Race, religion, region and abortion attitudes. Sociological Analysis. 1992. March 1;53[1]:97–105. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Cowan SK. Cohort abortion measures for the United States. Population and development review. 2013. June;39[2]:289–307. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00592.x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Ebaugh HR, Haney CA. Shifts in abortion attitudes: 1972–1978. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1980. August 1:491–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Petersen LR. Religion, plausibility structures, and education's effect on attitudes toward elective abortion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001. June;40[2]:187–204. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Figueira-McDonough J. Men and women as interest groups in the abortion debate in the United States. In Women's studies international forum 1989. January 1 [Vol. 12, No. 5, pp. 539–550]. Pergamon. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Strickler J, Danigelis NL. Changing frameworks in attitudes toward abortion. In Sociological Forum 2002. June 1 [Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 187–201]. Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Blake J. Abortion and public opinion: The 1960–1970 decade. Science. 1971. February 12;171[3971]:540–9. 10.1126/science.171.3971.540 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Cooper T. Race, Class, and Abortion: How Liberation Theology Enhances the Demand for Reproductive Justice. Feminist Theology. 2016. May;24[3]:226–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Bartkowski JP, Ramos‐Wada AI, Ellison CG, Acevedo GA. Faith, race‐ethnicity, and public policy preferences: Religious schemas and abortion attitudes among US Latinos. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2012. June;51[2]:343–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Ellison CG, Echevarria S, Smith B. Religion and abortion attitudes among US Hispanics: Findings from the 1990 Latino national political survey. Social Science Quarterly. 2005. March;86[1]:192–208. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Guth JL, Smidt CE, Kellstedt LA, Green JC. The sources of antiabortion attitudes: The case of religious political activists. American Politics Quarterly. 1993. January;21[1]:65–80. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Hess JA, Rueb JD. Attitudes toward abortion, religion, and party affiliation among college students. Current Psychology. 2005. March 1;24[1]:24–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Hoffmann JP, Johnson SM. Attitudes toward abortion among religious traditions in the United States: Change or continuity?. Sociology of Religion. 2005. July 1;66[2]:161–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Hoffmann JP, Miller AS. Social and political attitudes among religious groups: Convergence and divergence over time. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1997. March 1:52–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Doherty, C & Suls, R. Widening Regional Divide over Abortion Laws, Pew Research Centre, 2013. accessed from http://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/legacy-pdf/07-29-13-Abortion-Release.pdf

- 25. Jelen TG. Public Attitudes Toward Abortion and LGBTQ Issues: A dynamic analysis of region and partisanship. Sage Open. 2017. March;7[1]:2158244017697362. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Smith C. Change over time in attitudes about abortion laws relative to recent restrictions in Texas. Contraception. 2016. November 1;94[5]:447–52. 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.06.005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Adams GD. Abortion: Evidence of an issue evolution. American Journal of Political Science. 1997. July 1:718–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Carsey TM, Layman GC. Changing sides or changing minds? Party identification and policy preferences in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science. 2006. April;50[2]:464–77. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Jaenicke DW. Abortion and partisanship in the US Congress, 1976–2000: increasing partisan cohesion and differentiation. Journal of American Studies. 2002. April;36[1]:1–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Lai R. Abortion Bans: 9 States Have Passed Bills to Limit the Procedure This Year. New York Times , 2019. Accessed on 06/11/19 from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/us/abortion-laws-states.html [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Stout CT, Kretschmer K, Ruppanner L. Gender linked fate, race/ethnicity, and the marriage gap in American politics. Political Research Quarterly. 2017. September;70[3]:509–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Hout M. Abortion politics in the United States, 1972–1994: From single issue to ideology. Gender Issues. 1999. March 1;17[2]:3–4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Kelley J, Evans MD, Headey B. Moral reasoning and political conflict: The abortion controversy. British Journal of Sociology. 1993. December. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Newport F. Men, Women Generally Hold Similar Abortion Attitudes, 2018, Gallup News Service. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Zigerell LJ, Barker DC. Safe, Legal, Rare… and Early: Gender and the Politics of Abortion. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. 2011. February 1;21[1]:83–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Barkan SE. Gender and abortion attitudes: Religiosity as a suppressor variable. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2014. January 1;78[4]:940–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Bumpass LL. The measurement of public opinion on abortion: the effects of survey design. Family Planning Perspectives. 1997. July 1;29:177–80. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Dawson MC. Behind the mule: Race and class in African-American politics. Princeton University Press; 1995. July 23. [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Jaffe S. Why Did a Majority of White Women Vote for Trump?. In New Labor Forum 2018. January [Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 18–26]. Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Cohen SA. Abortion and women of color. Conscience. 2008. December 1;29[3]:37. [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Price K. What is reproductive justice?: How women of color activists are redefining the pro-choice paradigm. Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism. 2010. April 1;10[2]:42–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Merolla JL. White Female Voters in the 2016 Presidential Election. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics. 2018. March;3[1]:52–4. [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. American Fact Finder. Marital Status: 2013–2017 American Community 5-year Estimates. Retrieved on June 3,2019 from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_S1201&prodType=table

- 44. Miller AH, Gurin P, Gurin G, Malanchuk O. Group consciousness and political participation. American journal of political science. 1981. August 1:494–511. [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Gay C, Tate K. Doubly bound: The impact of gender and race on the politics of black women. Political Psychology. 1998. March;19[1]:169–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Sanchez GR, Vargas ED. Taking a closer look at group identity: the link between theory and measurement of group consciousness and linked fate. Political Research Quarterly. 2016. March;69[1]:160–74. 10.1177/1065912915624571 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Tate K. From protest to politics: The new black voters in American elections. Harvard University Press; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Kingston PW, Finkel SE. Is there a marriage gap in politics?. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1987. February 1:57–64. [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Stoker L, Jennings MK. Life-cycle transitions and political participation: The case of marriage. American political science review. 1995. June;89[2]:421–33 [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Duleep HO, Sanders S. The decision to work by married immigrant women. ILR Review. 1993. July;46[4]:677–90. [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Becker GS. Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of labor economics. 1985. January 1;3[1, Part 2]:S33–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Abroms LC, Goldscheider FK. More work for mother: How spouses, cohabiting partners and relatives affect the hours mothers work. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2002. June 1;23[2]:147–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. García-Manglano J. Opting out and leaning in: The life course employment profiles of early baby boom women in the United States. Demography. 2015. December 1;52[6]:1961–93. 10.1007/s13524-015-0438-6 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Dow DM. Integrated motherhood: Beyond hegemonic ideologies of motherhood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2016. February;78[1]:180–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Harris KM. Work and welfare among single mothers in poverty. American Journal of Sociology. 1993. September 1;99[2]:317–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Gerson K., 2009. The unfinished revolution: Coming of age in a new era of gender, work, and family. Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Bolzendahl CI, Myers DJ. Feminist attitudes and support for gender equality: Opinion change in women and men. Social Forces. 2004. December; 83[2]:759–790. [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Gupta S. The effects of transitions in marital status on men's performance of housework. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999:700–11. [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Brines J. Economic Dependency, Gender, and the Division of Labor at Home. American Journal of Sociology. 1994;100[3]:652–88. [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Plutzer E. Preferences in family politics: Women's consciousness or family context?. Political Geography Quarterly. 1991. April 1;10[2]:162–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Zuo J, Tang S. Breadwinner status and gender ideologies of men and women regarding family roles. Sociological perspectives. 2000. March;43[1]:29–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Chong D, Citrin J, Conley P. When self‐interest matters. Political Psychology. 2001. September;22[3]:541–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Collins T, Moyer L. Gender, Race, and Intersectionality on the Federal Appellate Bench. Political Research Quarterly. 2008;61(2):219–27. [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Junn J, Masuoka N. Asian American identity: Shared racial status and political context. Perspectives on Politics. 2008. December;6[4]:729–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Wang W, Parker K, Taylor P. Breadwinner moms: mothers are the sole or primary provider in four-in-ten households with children-public conflicted about the growing trend. 2013. Pew Research Centre, Washington DC. [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Simien EM. Black feminist voices in politics. SUNY Press; 2006. July 6. [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Baxter S, Lansing M. Women and politics: The visible minority. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1983. [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Kane EW. Racial and ethnic variations in gender-related attitudes. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000. August 1; 26[1]:419–439. [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Sayer LC, Fine L. Racial-ethnic differences in US married women’s and men’s housework. Social Indicators Research. 2011. April 1;101[2]:259–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- 70. Roehling P, Hernandez-Jarvis L, Swope H. Variations in negative work-family spillover among white, black, Hispanic American men and women. Does ethnicity matter? Journal of Family Issues. 2005. September 1; 26: 840–865. [ Google Scholar ]

- 71. Silber Mohamed H. Americana or Latina? Gender and identity acquisition among Hispanics in the United States. Politics, Groups, and Identities. 2015. January 2;3[1]:40–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- 72. Sanchez GR, Masuoka N. Brown-utility heuristic? The presence and contributing factors of Latino linked fate. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010. November;32[4]:519–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- 73. Stokes AK. Latino group consciousness and political participation. American Politics Research. 2003. July;31[4]:361–78. [ Google Scholar ]

- 74. Lenth R. Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version. 2018;1[1]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 75. Lange T, Vansteelandt S, Bekaert M. A simple unified approach for estimating natural direct and indirect effects. American journal of epidemiology. 2012. July 10;176[3]:190–5. 10.1093/aje/kwr525 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 76. Steen J, Loeys T, Moerkerke B, Vansteelandt S. Medflex: an R package for flexible mediation analysis using natural effect models. Journal of Statistical Software. 2017;76[11]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 77. Dolan J, Deckman MM, Swers ML. Women and politics: Paths to power and political influence. Rowman & Littlefield; 2017. June 1. [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data availability statement.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (723.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections