- Funding Sources

Q: How to write the introduction of a research proposal?

What do I include in the introduction of a research proposal?

Asked on 05 Jun, 2019

Writing an effective research proposal is essential to acquire funding for your research. The introduction, being the first part of your proposal, must provide the funders a clear understanding of what you plan to do. A well written introduction will help make a compelling case for your research proposal.

To begin with, the introduction must set context for your research by mentioning what is known about the topic and what needs to be explored further. In the introduction, you can highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge in your field and to overall scientific development.

The introduction must also contain a hypothesis that led to the development of the research design. You can come up with this hypotheis by asking yourself questions like:

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Why is this research important, what is its significance, and how will its outcomes affect the funders and the society on the whole?

Here are some excellent resources to help you write a great proposal:

- COURSE: How to write a grant proposal

- 10 Tips to write an effective research grant proposal

- INFOGRAPHIC: 9 Core parts every grant proposal must contain

- INFOGRAPHIC: 15 Key tips for writing a winning grant proposal

Answered by Editage Insights on 10 Jun, 2019

- Upvote this Answer

This content belongs to the Career Growth Stage

Confirm that you would also like to sign up for free personalized email coaching for this stage.

Trending Searches

- Statement of the problem

- Background of study

- Scope of the study

- Types of qualitative research

- Rationale of the study

- Concept paper

- Literature review

- Introduction in research

- Under "Editor Evaluation"

- Ethics in research

Recent Searches

- Review paper

- Responding to reviewer comments

- Predatory publishers

- Scope and delimitations

- Open access

- Plagiarism in research

- Journal selection tips

- Editor assigned

- Types of articles

- "Reject and Resubmit" status

- Decision in process

- Conflict of interest

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

Table of Contents

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1

What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

What is the introduction for a research paper?

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

Why is the introduction important in a research paper?

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address.

Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

1. Introduce the research topic:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

2. Determine a research niche:

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

3. Place your research within the research niche:

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

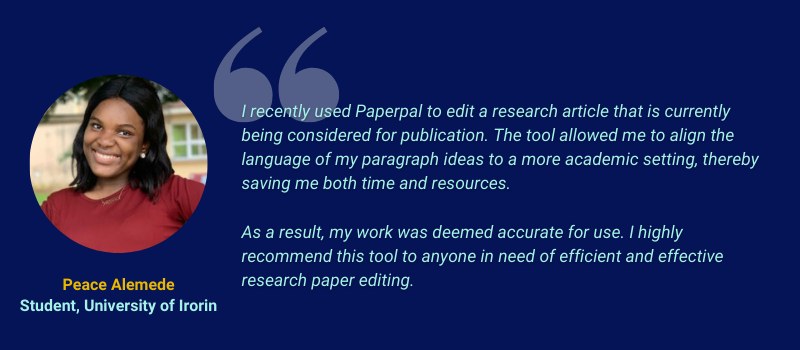

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI academic writing assistant that helps you write 2x faster. Trained on millions of scholarly articles and leveraging over 22 years of STM expertise, Paperpal understands and preserves academic context. This ensures that its language suggestions and AI-generated text not only meets stringent linguistic standards but also aligns with academic writing conventions.

If you’re stuck with writing a research paper introduction, Paperpal’s generative AI features can help you with the starting point and keep your writing momentum going. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

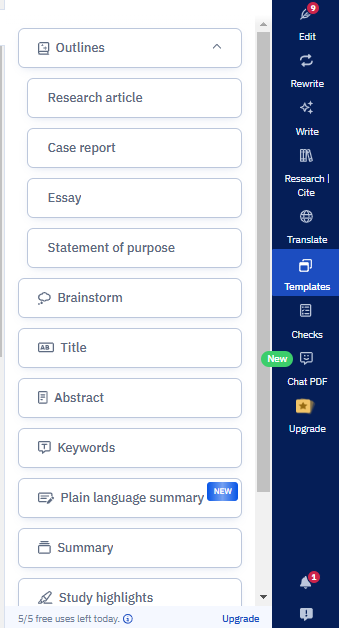

Step 1: Sign up/log in to Paperpal and click on the Templates feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article .

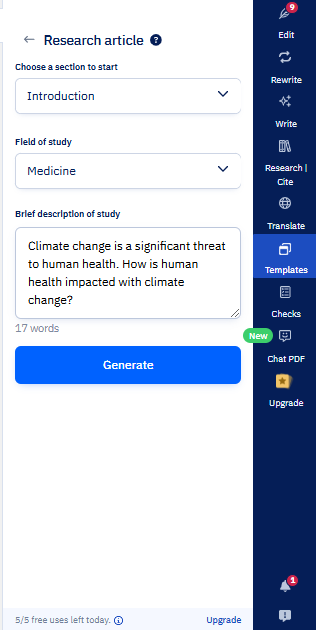

Step 2: Choose the section of the research article you wish to get an outline for and fill the other details like Field of study, Brief description of study.

Step 3: Based on your inputs, Paperpal generates an outline for your research paper introduction. Check the introduction and personalize it according to your research paper topic.

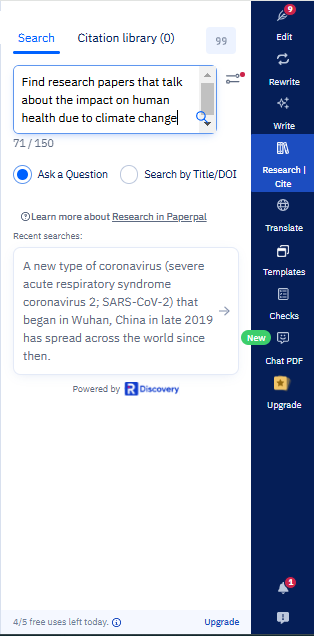

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, search for relevant references and cite them in your research paper draft effortlessly with Paperpal.

Step 5: Once your research paper introduction is done, check for grammatical errors with Paperpal’s language checks and prepare it for submission.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

Start Writing with Paperpal

Key points to remember

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the purpose of the introduction in research papers.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

How long should the research paper introduction be?

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2

For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

What should be included in the research paper introduction?

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3

Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction.

- Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic.

- Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects.

- Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought.

- Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance.

- Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study

- Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Should I include citations in the introduction for a research paper?

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through.

Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review.

A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

Should I provide a literature review in the research paper introduction?

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following:

- Introduces the topic

- Establishes the study’s significance

- Provides an overview of the relevant literature

- Provides context for the study using literature

- Identifies knowledge gaps

However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction:

- Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research

- Avoid direct quoting

- Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

- Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

- Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

- Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

- Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, what is the background of a study and..., what is scispace detailed review of features, pricing,..., what is the significance and use of post-hoc..., how to write a case study in research..., online ai writing tools: cost-efficient help for dissertation..., how to cite in apa format (7th edition):..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide).

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

A research proposal is a formal document that outlines the purpose, scope, methodology, and significance of a proposed study. It serves as a roadmap for the research project and is essential for securing approval, funding, or academic support. Writing a clear and compelling research proposal is crucial, whether for academic research, grants, or professional projects. This article provides a step-by-step guide and a template for creating an effective research proposal.

How To Write a Research Proposal

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Research Proposal

1. Title Page

The title page should include:

- The title of the proposal (concise and descriptive).

- The researcher’s name and affiliation.

- The date of submission.

- The name of the supervisor, institution, or funding organization (if applicable).

2. Abstract

Write a brief summary of the research proposal, highlighting:

- The research problem or question.

- The objectives of the study.

- A concise overview of the methodology.

- The significance of the research.

The abstract should be approximately 150–250 words.

3. Introduction

The introduction sets the context for the study and captures the reader’s interest. Include:

- Background Information: Explain the broader context of the research area.

- Research Problem: Define the specific issue or gap in knowledge the research will address.

- Objectives: Clearly outline what the research aims to achieve.

- Research Questions: Present the central questions the study seeks to answer.

- Significance: Highlight the importance and potential impact of the study.

4. Literature Review

Summarize existing research relevant to your topic, demonstrating your understanding of the field.

- Identify Gaps: Highlight gaps or limitations in current knowledge.

- Theoretical Framework: Discuss theories or models that underpin the study.

- Connection to Research: Explain how your research builds on or diverges from existing studies.

5. Research Methodology

Provide a detailed description of how you plan to conduct the research. Include:

- Research Design: Specify whether the study is qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods.

- Population and Sampling: Define the target population and sampling methods.

- Data Collection Methods: Describe the tools (e.g., surveys, interviews, experiments) and procedures for gathering data.

- Data Analysis Techniques: Explain how the data will be analyzed (e.g., statistical methods, thematic analysis).

- Ethical Considerations: Address ethical issues, such as informed consent and confidentiality.

6. Expected Results

Discuss the anticipated outcomes of the research.

- Predictions: Provide a hypothesis or expected findings based on existing knowledge.

- Contribution to Knowledge: Highlight how the findings will advance the field or solve the research problem.

7. Timeline

Create a timeline for completing the research, including key milestones.

- Month 1-2: Literature review and proposal finalization.

- Month 3-4: Data collection.

- Month 5-6: Data analysis and report writing.

8. Budget (if applicable)

Detail the financial resources required for the research. Include:

- Equipment costs.

- Participant incentives.

- Travel and accommodation expenses.

- Software or licensing fees.

9. References

Include a comprehensive list of all sources cited in the proposal. Use a citation style appropriate for your discipline (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago).

10. Appendices (optional)

Attach supplementary materials, such as:

- Questionnaires or survey instruments.

- Data collection templates.

- Ethical approval forms.

Research Proposal Template

- Title of Proposal

- Researcher’s Name and Affiliation

- Date of Submission

- Supervisor/Institution

1. Introduction

- Background Information

- Research Problem

- Research Questions

- Significance

2. Literature Review

- Summary of Existing Research

- Gaps in Knowledge

- Theoretical Framework

3. Research Methodology

- Research Design

- Population and Sampling

- Data Collection Methods

- Data Analysis Techniques

- Ethical Considerations

4. Expected Results

5. timeline, 6. budget (if applicable), 7. references, 8. appendices (optional), tips for writing a strong research proposal.

- Be Clear and Concise: Avoid jargon and write in straightforward language.

- Align Objectives with Methods: Ensure your research design supports your objectives.

- Justify the Research: Highlight its importance and potential impact.

- Proofread Thoroughly: Check for grammatical errors and formatting inconsistencies.

- Seek Feedback: Share your draft with peers or supervisors for constructive input.

Writing a research proposal is a critical step in planning and securing support for your research project. By following the step-by-step guide and using the provided template, you can create a well-structured and compelling proposal. A strong research proposal not only demonstrates your understanding of the topic but also conveys the feasibility and significance of your study, laying the foundation for successful research.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . Sage Publications.

- Punch, K. F. (2016). Developing Effective Research Proposals . Sage Publications.

- Babbie, E. (2020). The Practice of Social Research . Cengage Learning.

- University of Southern California Libraries (2023). Research Guides: Writing a Research Proposal .

- Locke, L. F., Spirduso, W. W., & Silverman, S. J. (2013). Proposals That Work: A Guide for Planning Dissertations and Grant Proposals . Sage Publications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

Research Proposal – Types, Template and Example

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Resources

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools; Swales, John, and Hazem Najjar. "The Writing of Research Article Introductions." Written Communication 4 (April 1987): 175-191.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education; Swales, John, and Hazem Najjar. "The Writing of Research Article Introductions." Written Communication 4 (April 1987): 175-191.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

Below is a general outline for thinking about the introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: Dec 19, 2024 2:30 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 14: The Research Proposal

14.3 Components of a Research Proposal

Krathwohl (2005) suggests and describes a variety of components to include in a research proposal. The following sections – Introductions, Background and significance, Literature Review; Research design and methods, Preliminary suppositions and implications; and Conclusion present these components in a suggested template for you to follow in the preparation of your research proposal.

Introduction

The introduction sets the tone for what follows in your research proposal – treat it as the initial pitch of your idea. After reading the introduction your reader should:

- understand what it is you want to do;

- have a sense of your passion for the topic; and

- be excited about the study’s possible outcomes.

As you begin writing your research proposal, it is helpful to think of the introduction as a narrative of what it is you want to do, written in one to three paragraphs. Within those one to three paragraphs, it is important to briefly answer the following questions:

- What is the central research problem?

- How is the topic of your research proposal related to the problem?

- What methods will you utilize to analyze the research problem?

- Why is it important to undertake this research? What is the significance of your proposed research? Why are the outcomes of your proposed research important? Whom are they important?

Note : You may be asked by your instructor to include an abstract with your research proposal. In such cases, an abstract should provide an overview of what it is you plan to study, your main research question, a brief explanation of your methods to answer the research question, and your expected findings. All of this information must be carefully crafted in 150 to 250 words. A word of advice is to save the writing of your abstract until the very end of your research proposal preparation. If you are asked to provide an abstract, you should include 5 to 7 key words that are of most relevance to your study. List these in order of relevance.

Background and Significance

The purpose of this section is to explain the context of your proposal and to describe, in detail, why it is important to undertake this research. Assume that the person or people who will read your research proposal know nothing or very little about the research problem. While you do not need to include all knowledge you have learned about your topic in this section, it is important to ensure that you include the most relevant material that will help to explain the goals of your research.

While there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and provide a more thorough explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction.

- Present the rationale for the proposed research study. Clearly indicate why this research is worth doing. Answer the “so what?” question.

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Do not forget to explain how and in what ways your proposed research builds upon previous related research.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research.

- Clearly identify the key or most relevant sources of research you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research, in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what will be excluded from your study.

- Provide clear definitions of key concepts and terms. Since key concepts and terms often have numerous definitions, make sure you state which definition you will be utilizing in your research.

Literature Review

This key component of the research proposal is the most time-consuming aspect in the preparation of your research proposal. As described in Chapter 5 , the literature review provides the background to your study and demonstrates the significance of the proposed research. Specifically, it is a review and synthesis of prior research that is related to the problem you are setting forth to investigate. Essentially, your goal in the literature review is to place your research study within the larger whole of what has been studied in the past, while demonstrating to your reader that your work is original, innovative, and adds to the larger whole.

As the literature review is information dense, it is essential that this section be intelligently structured to enable your reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study. However, this can be easier to state and harder to do, simply due to the fact there is usually a plethora of related research to sift through. Consequently, a good strategy for writing the literature review is to break the literature into conceptual categories or themes, rather than attempting to describe various groups of literature you reviewed. Chapter 5 describes a variety of methods to help you organize the themes.

Here are some suggestions on how to approach the writing of your literature review:

- Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they used, what they found, and what they recommended based upon their findings.

- Do not be afraid to challenge previous related research findings and/or conclusions.

- Assess what you believe to be missing from previous research and explain how your research fills in this gap and/or extends previous research.

It is important to note that a significant challenge related to undertaking a literature review is knowing when to stop. As such, it is important to know when you have uncovered the key conceptual categories underlying your research topic. Generally, when you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations, you can have confidence that you have covered all of the significant conceptual categories in your literature review. However, it is also important to acknowledge that researchers often find themselves returning to the literature as they collect and analyze their data. For example, an unexpected finding may develop as you collect and/or analyze the data; in this case, it is important to take the time to step back and review the literature again, to ensure that no other researchers have found a similar finding. This may include looking to research outside your field.

This situation occurred with one of this textbook’s authors’ research related to community resilience. During the interviews, the researchers heard many participants discuss individual resilience factors and how they believed these individual factors helped make the community more resilient, overall. Sheppard and Williams (2016) had not discovered these individual factors in their original literature review on community and environmental resilience. However, when they returned to the literature to search for individual resilience factors, they discovered a small body of literature in the child and youth psychology field. Consequently, Sheppard and Williams had to go back and add a new section to their literature review on individual resilience factors. Interestingly, their research appeared to be the first research to link individual resilience factors with community resilience factors.

Research design and methods

The objective of this section of the research proposal is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will enable you to solve the research problem you have identified and also enable you to accurately and effectively interpret the results of your research. Consequently, it is critical that the research design and methods section is well-written, clear, and logically organized. This demonstrates to your reader that you know what you are going to do and how you are going to do it. Overall, you want to leave your reader feeling confident that you have what it takes to get this research study completed in a timely fashion.

Essentially, this section of the research proposal should be clearly tied to the specific objectives of your study; however, it is also important to draw upon and include examples from the literature review that relate to your design and intended methods. In other words, you must clearly demonstrate how your study utilizes and builds upon past studies, as it relates to the research design and intended methods. For example, what methods have been used by other researchers in similar studies?

While it is important to consider the methods that other researchers have employed, it is equally, if not more, important to consider what methods have not been but could be employed. Remember, the methods section is not simply a list of tasks to be undertaken. It is also an argument as to why and how the tasks you have outlined will help you investigate the research problem and answer your research question(s).

Tips for writing the research design and methods section

Specify the methodological approaches you intend to employ to obtain information and the techniques you will use to analyze the data.

Specify the research operations you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results of those operations in relation to the research problem.

Go beyond stating what you hope to achieve through the methods you have chosen. State how you will actually implement the methods (i.e., coding interview text, running regression analysis, etc.).

Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers you may encounter when undertaking your research, and describe how you will address these barriers.

Explain where you believe you will find challenges related to data collection, including access to participants and information.

Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

The purpose of this section is to argue how you anticipate that your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the area of your study. Depending upon the aims and objectives of your study, you should also discuss how your anticipated findings may impact future research. For example, is it possible that your research may lead to a new policy, theoretical understanding, or method for analyzing data? How might your study influence future studies? What might your study mean for future practitioners working in the field? Who or what might benefit from your study? How might your study contribute to social, economic or environmental issues? While it is important to think about and discuss possibilities such as these, it is equally important to be realistic in stating your anticipated findings. In other words, you do not want to delve into idle speculation. Rather, the purpose here is to reflect upon gaps in the current body of literature and to describe how you anticipate your research will begin to fill in some or all of those gaps.

The conclusion reiterates the importance and significance of your research proposal, and provides a brief summary of the entire proposed study. Essentially, this section should only be one or two paragraphs in length. Here is a potential outline for your conclusion:

Discuss why the study should be done. Specifically discuss how you expect your study will advance existing knowledge and how your study is unique.

Explain the specific purpose of the study and the research questions that the study will answer.

Explain why the research design and methods chosen for this study are appropriate, and why other designs and methods were not chosen.

State the potential implications you expect to emerge from your proposed study,

Provide a sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship currently in existence, related to the research problem.

Citations and References

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your research proposal. In a research proposal, this can take two forms: a reference list or a bibliography. A reference list lists the literature you referenced in the body of your research proposal. All references in the reference list must appear in the body of the research proposal. Remember, it is not acceptable to say “as cited in …” As a researcher you must always go to the original source and check it for yourself. Many errors are made in referencing, even by top researchers, and so it is important not to perpetuate an error made by someone else. While this can be time consuming, it is the proper way to undertake a literature review.

In contrast, a bibliography , is a list of everything you used or cited in your research proposal, with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem. In other words, sources cited in your bibliography may not necessarily appear in the body of your research proposal. Make sure you check with your instructor to see which of the two you are expected to produce.

Overall, your list of citations should be a testament to the fact that you have done a sufficient level of preliminary research to ensure that your project will complement, but not duplicate, previous research efforts. For social sciences, the reference list or bibliography should be prepared in American Psychological Association (APA) referencing format. Usually, the reference list (or bibliography) is not included in the word count of the research proposal. Again, make sure you check with your instructor to confirm.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

Subject index

Pam Denicolo and Lucinda Becker recognize the importance of developing an effective research proposal for gaining either a place on a research degree program or funding to support research projects and set out to explore the main factors that that proposal writers need to attend to in developing successful proposals of their own. Developing Research Proposals will help readers to understand the context within which their proposal will be read, what the reviewers are looking for and will be influenced by, while also supporting the development of relevant skills through advice and practical activities. The authors draw together the key elements in the process of preparing and submitting a proposal and concludes with advice on responding to the results, successful or not, and their relevance to future proposals.

What Should be Included in the Introduction, Rationale and Literature Review?

- By: Pam Denicolo & Lucinda Becker

- In: Developing Research Proposals

- Chapter DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781526402226.n4

- Subject: Anthropology , Business and Management , Criminology and Criminal Justice , Communication and Media Studies , Economics , Education , Geography , Health , Marketing , Nursing , Political Science and International Relations , Psychology , Social Work , Sociology

- Show page numbers Hide page numbers

Chapter Overview

This chapter discusses:

- the reasons for including each of the early sections: introduction, rationale, literature review;

- what each should contain and why;

- details of the requirements of different forms of literature review;

- searching the literature;

- developing your argument.

Orientating the Reader to your Purpose

We are presenting these three topics that feature in proposals – introduction, rationale and literature review – using their most explicitly descriptive titles, because for some purposes and audiences these are potential sections of a document or they may be combined, with any two of them being sub-sections under the heading of the third. Alternatively, they could be presented as ‘introduction including a rationale and followed by a literature review’ or in some other formulation using such synonyms such as ‘background, needs statement and supporting argument’. [Page 44]

Whichever of these is popular in your discipline/culture and for your purpose and audience, the following advice and discussion will be relevant. One of the most important points is that this part of the proposal should be clearly structured to follow a story line that develops an argument supporting your choice of topic and research hypotheses/questions. These latter form the cornerstone of your project and your proposal; indeed, you may be required on funders’ forms to declare them before going into further details. Thus they act as a first sift level to reviewers and so should be precise but intriguing. The proposal also needs to demonstrate that they are well-founded and appropriate to context, hence the need for a clear introduction, rationale and sound literature review.

The Introduction

It is often helpful to the reader to start the introduction with a clear statement of the overarching purpose of the study and then round off the introduction with its aims and objectives to emphasise the more focussed purpose, again moving from the general to the particular as in the development of the theoretical context, or main review. It is not untoward to include in the introduction to the proposal a short explanation of how your interest in the topic was stimulated, because this also gives you an opportunity to demonstrate how your prior experience and acquired skills make you competent to carry out the research.

If a substantial, rather than preliminary, literature review is required then it is helpful in the introduction to give the reader guidance for the journey, explaining how your argument will develop through the sections and perhaps themes within them.

The Rationale

The development of the conceptual framework for your work demands a transparent rationale. This is where you present your case for the project being a significant enterprise, not simply an interesting question or proposition. Interesting questions abound but the scarcity of funding or of available resources for teaching/research support demands more than the topic being intellectually interesting. There will be an expectation from your reviewers that a worthwhile study will have the potential to contribute to knowledge in a non-trivial way, doing research that has not been done before and producing an outcome which perhaps has significance for policy or practice or both as well as furthering understanding. You have to construct an argument or case [Page 45] that will not disappoint those reviewers so make sure that you not only draw on literature sources that support your choice of purpose and help hone it into specific research questions or hypotheses but also acknowledge and critique those previous writings that contradict your argument or subscribe to an alternative analysis of the situation. This will make your case more convincing and will demonstrate that you are aware of controversies in the field and are not afraid to engage with them.

Preparing for the Literature Review

Developing this awareness, though, requires a lot of exploration of the literature, frustratingly numerous blind alleys and probably stacks of notes (metaphorical ones on the computer if not in hard copy). So it is wise to begin by adopting a system for storing the reference information in a way that facilitates retrieving aspects of it. In the ‘other useful resources’ section of Appendix 2 we have noted introductions to the End Note package – this is software for reference management and perhaps one of the most useful electronic methods of storing and retrieving references to date – but if your circumstances demand a low-tech approach then opt for a card-index system that also allows for cross-referencing. (A simple one involves alphabetical author arrangement of index cards in separate boxes for each topic area with perhaps a colour code per topic so that publications dealing with several topics can be readily identified by the multiple colours.) Because any exercise of organising your references marks the beginning of what you hope will be an extensive commitment, it is worthwhile establishing an efficient system early in the process. Any good librarian will be able to advise you on a range of information storage and retrieval devices.

An efficient system for creating a bibliography from which to select your reference lists for different academic purposes includes assiduous attention to detail because you will require page numbers for quotations and full bibliographic detail in references, whichever style you choose or is required by your selected audience. One convention is to provide only the surname/s of the author/s or editor/s with the date of publication in the actual body of the text (e.g. Sparrow, 1999, or Thrush and Swift, 2010, or Pigeon et al., 2009) and a list, entitled ‘References’, with full reference details in alphabetical order at the end of the proposal. Another convention is to cite the authors or editors with a numerical superscript in the text and a full reference as a correctly numbered footnote on the same page. All referencing conventions will require you to know the authors’ (or editors’) surnames and initials, the date of publication, the title, the place of publication and the publisher, though the order and style of presentation may vary depending on the system chosen (see Appendix 2 for books on referencing or seek the help of a librarian). [Page 46]

There are conventions to be adhered to also in the way that book chapters, journal articles and internet references are presented. Again, the aid of a librarian with this will be invaluable if an example of the required format is not included with the application details. Attention to detail is a strict requirement, so try not to get irritated when some of your proposal target audiences require full stops after author initials while others do not, because the way you reference your proposal indicates to the reviewers that you will be able and willing to use their preferred convention in your prospective final report.

One particular convention to be alert to is that of seeking out primary sources whenever it is possible. The rationale for this is that you can never be sure that a ‘secondary’ author has correctly understood and/or accurately quoted the original source; it is all too easy to abstract a sentence or two that seems to support one's argument without paying attention to context and tone. This is a trap that you need to guard against in your own presentation too, because your reviewers may be more familiar with the literature than you are and so spot a misquotation or incorrect attribution.

The Literature Review Itself

For a research degree proposal , even one for which you are also seeking funding, only a preliminary review of the literature is usually required because there is an expectation that further work will be done on this during the course of study. However, the review included should demonstrate that you are conversant with the appropriate range of literature, particularly key and recent publications that pertain to your proposed topic. These serve to indicate that you have some basic skills of information retrieval and organisation that contribute to a justification for a developing topic focus.

For a proposal for research funding for a project beyond research degree level there are different requirements, whether the project is one of your own devising or one that is to fit in with the funders’ own framework. You will be expected to be thoroughly conversant with the topic and others’ views on it as expressed in the literature as this will demonstrate that you have expertise in the topic area and in information retrieval and organisation. Seldom will the literature review form a time-consuming part of and/or a key aspect of the research for which you are seeking financial support, unless the research is genuinely into a previously unexplored area that requires consideration of overlapping or cognate areas as they emerge during the process of exploration, or unless the focus of your project is the literature itself. More likely during the funded research project, you will simply be keeping up to date a literature base that you produced to formulate your proposal argument for funding.

The size of the review should reflect the degree of depth of exploration, not merely the number of references accessed. It will depend on the situation, whether seeking a degree place or funding , and the requirements of the proposal [Page 47] reviewer, but also on the proposed approach to the empirical work. At one extreme, for a project in a well-researched area seeking substantial funding to move the boundaries forward, a full, systematic literature review will be required to support the specific focus. This will take the form of a thorough search of the full literature using explicit eligibility criteria to identify studies with valid evidence, which are then rigorously appraised for their significance to the research topic. At the other extreme, if a grounded theory approach is taken (see the Glossary and the section entitled ‘Research using interpretivist approaches’ in Chapter 6 ), then the literature will be reviewed as it becomes relevant to emerging data and concepts so that the proposal requires an introduction and rationale but not a formal literature review. In between there can be a review that identifies a region within a topic area that appears to be under-researched, with a further review suggested to focus in greater depth as the project progresses.

Another key consideration when preparing the review is that this part of the proposal should demonstrate the insightfulness of your selection of book/articles to review. These documents should be demonstrably relevant to the purpose of your research, a statement of which can usefully form the starting point of your introduction or background description. (Most definitely it should not be taken as an opportunity to demonstrate how many books and articles you have read in the discipline.) This section should also frame the research by briefly describing the context of the present research, perhaps including the historical background to the general area and then locating the specific topic within the contemporary context, so that the relevant theoretical discourse can be identified. It follows from this that you should show how your study fits into a particular view of how science (meaning research in general, not the disciplines per se) should be conducted, what system of meanings it relates to and what assumptions are being made. This is sometimes called the research paradigm , or perspective taken, in the literature. We will discuss this in greater depth in Chapters 5 and 6 but note its relevance here because the pervading paradigm will influence what kind of questions are asked about the world. If the paradigm is stated early on, the reader can be orientated towards what to expect from the rest of the proposal so that false expectations are not raised.

Thus a brief indication of the body of literature that provides the context for your study will be sufficient because you must quickly, but with a transparent rationale, focus on the substantive theories and pertinent issues, the niche area in which your research lies. Within that it is important to identify the key authors, those who contributed to the historical development of ideas, the landmark studies that should be given credit, as well as those researchers/authors who are currently involved in the field, producing new theoretical insights. This process involves much reading through an analytical lens, noticing which studies and authors are most frequently referenced, which seem to be most representative of the area, as well as those that are influential and those that produce the most cogent arguments. It is important to remember not to neglect opponents as well as proponents of key interpretations (and overlaps [Page 48] with other bodies of literature) so that you can familiarise yourself thoroughly with the debates that pervade the subject.

The Process of Searching the Literature

Accessing this literature is a process of identifying appropriate key words and using them to search computerised databases in your field. Your librarian can advise you on this, and introduce you to academic search engines, but you need to be clear about your own conceptual framework first so that the more obvious words emerge and then synonyms and related concepts can be considered using a thesaurus. At first you may find a very large number of publications being generated by your first keyword/s so you will need to refine the search, perhaps by combining words/concepts (e.g. only A when it is with B). It is sensible only to seek out Abstracts at first, before trying to access the full publication, reviewing these to ensure that they do cover what the word search indicates – not all will, you will find. The experience, common to most researchers, of being occasionally disappointed that key words do not unlock insights into the topics you are interested in, emphasises the need to produce accurate Abstracts of your own work, a topic we will, apparently perversely, turn to in the final chapter.

You will discover too that a review is a process of progressive focussing, starting with a wide canvas but gradually honing in on those selected publications that best support your choice of topic and approach to it. A simple analogy captures the essence of this. If you look up the key word ‘flowers’ on your computer search engine you may, like us, get 144,000,000 references; if you add in ‘nasturtiums’, the result then is 85,200; next join in ‘edibility’ and the number of references is reduced to 26,000; follow this by adding ‘UK vendors’ and at last a more manageable figure of 9,370 references is produced. This is still a large number so if you do want to study this area then a further refinement of key words is needed, though if you scan this current list then you will already recognise that some sources are frequently repeated.

Practice Literature Search

- 1. Just to get a feel for the task, access a computer and type into the web search engine the main descriptor of the realm you want to study. Note the number of sites found.

- 2. Then refine the descriptor in some sensible way and note the new number of sites.

- 3. Then refine the search by asking for scholarly journal articles on that topic.

(We tried ‘doctoral education’ – over 8.5 million sites; then added the scholarly articles refinement to reduce the number to about a quarter of a million …)

Constructing your Argument

Next, you must synthesise your own argument, drawing on your now refined literature set by reviewing in a critical manner the results presented and the methods used to produce them. Your argument should demonstrate clearly which issues have been robustly supported in the previous literature, and which issues are presented more tenuously or are controversial or even neglected, and therefore demand further investigation. You may find that there is a model that you can cite as your conceptual framework or one that requires development in the light of new evidence; you may be seeking to verify a theory or generate a new one so your literature review should not simply be a backward look at what previous research and writing has said to influence the focus of your research. It should also contain an element of prediction of how your research will contribute to the literature and what the results might add to the body of knowledge. Many research textbooks refer to ‘identifying a gap’ in the literature that your research is intended to bridge. This may be a phenomenon or method that is relatively unexplored or unexploited. All funders will expect some publication and dissemination of your work to materialise so acknowledge this fact in this section by showing the connections of your projected work to the existing literature, indicating what hole it will fill and which theories it seeks to substantiate, enhance, refine or confront.

A convincing argument can only be made through a logical presentation that is conceptually organised, with commonalities noted and comparisons made in some thematic way. If the review is extensive then sub-headings might be useful under which trends can be identified and limitations noted as you appraise previous work in the field. You must take care to acknowledge which ideas are your own and which you have derived from the work of others by careful referencing; similarly you should express all of this in your own words, only using quotations sparsely as illustration rather than substituting for your own formulation, so that you do not plagiarise the efforts of others. This is part of making the research project your own. Again, it is tempting to list a large number of other researchers or authors to give credibility to your argument, but it is wiser to demonstrate how conversant with the field you are by selecting the most significant of a list of potential references. If there are several important ones that support a point you are making then ensure that you are consistent in the way you present ‘strings’ of references. One convention is to list them in descending date order, that is, the most recent first, though some writers use alphabetic order of the first authors. Whichever convention you choose, stick with it in any one document.