- Privacy Policy

Educational Psyche

Inductive To Innovative

Kohler’s Insight Learning Theory: An In-Depth Exploration

Learning has always been a big area of interest in psychology and various theories have been developed to explain how we learn and acquire skills. Of all the theories, the Insight Learning Theory by Wolfgang Köhler stands out because of its focus on the mental restructuring that happens during problem solving. Unlike behaviourist models that focus on trial and error , Köhler’s theory highlights the importance of insight – that sudden realisation or understanding that often leads to problem solving breakthroughs. This article will dive into Köhler’s Learning by Insight Theory, its principles, experiments and lasting impact on psychology and education.

Table of Contents

Who is Wolfgang Köhler?

Wolfgang Köhler ⁽¹⁾ (1887-1967) was a German psychologist and a big name in Gestalt psychology which is all about holistic perception and problem solving. His work was all about the idea that we don’t respond to stimuli in parts but to situations as a whole. He along with Max Wertheimer and Kurt Koffka founded Gestalt psychology which says our mind is wired to recognize patterns, shapes and configurations as a whole not as the sum of its parts.

His most famous work came from his experiments with chimpanzees on the island of Tenerife where he tested how they solved complex problems. His findings led him to question the then prevailing behaviorist theories of B.F. Skinner and John Watson which said that learning happens through trial and error and conditioning.

The Insight Learning Theory

Insight learning is a sudden and often novel understanding of the solution to a problem. It’s different from incremental learning where solutions are reached step by step. Köhler’s experiments showed that problem solving could happen quickly and instinctively, without going through a detailed or logical process.

Insight Learning Theory Principles

- No Overt Reinforcement: Unlike behaviorist models, insight learning doesn’t rely on rewards or punishments. The “aha” moment is driven by the learner’s internal cognitive processing, not external stimuli.

- Transfer of Learning: Once a learner solves a problem with insight, they can apply the solution to similar problems. The learning isn’t situation specific as the learner understands the underlying principles.

- Understanding Over Memorization: Insight learning prioritizes understanding of relationships and structures over rote memorization. The learner moves beyond just recalling facts to understanding the underlying mechanics of the problem.

Köhler’s Chimpanzee Experiments

Köhler’s most famous work was with chimpanzees, especially Sultan, at the Prussian Academy of Sciences ’ anthropoid research station in Tenerife. His results supported the Insight Learning Theory.

These experiments showed chimpanzees could solve problems not through gradual conditioning or reinforcement but through cognitive processes that allowed them to see the solution and act on it.

Steps of Insight Learning

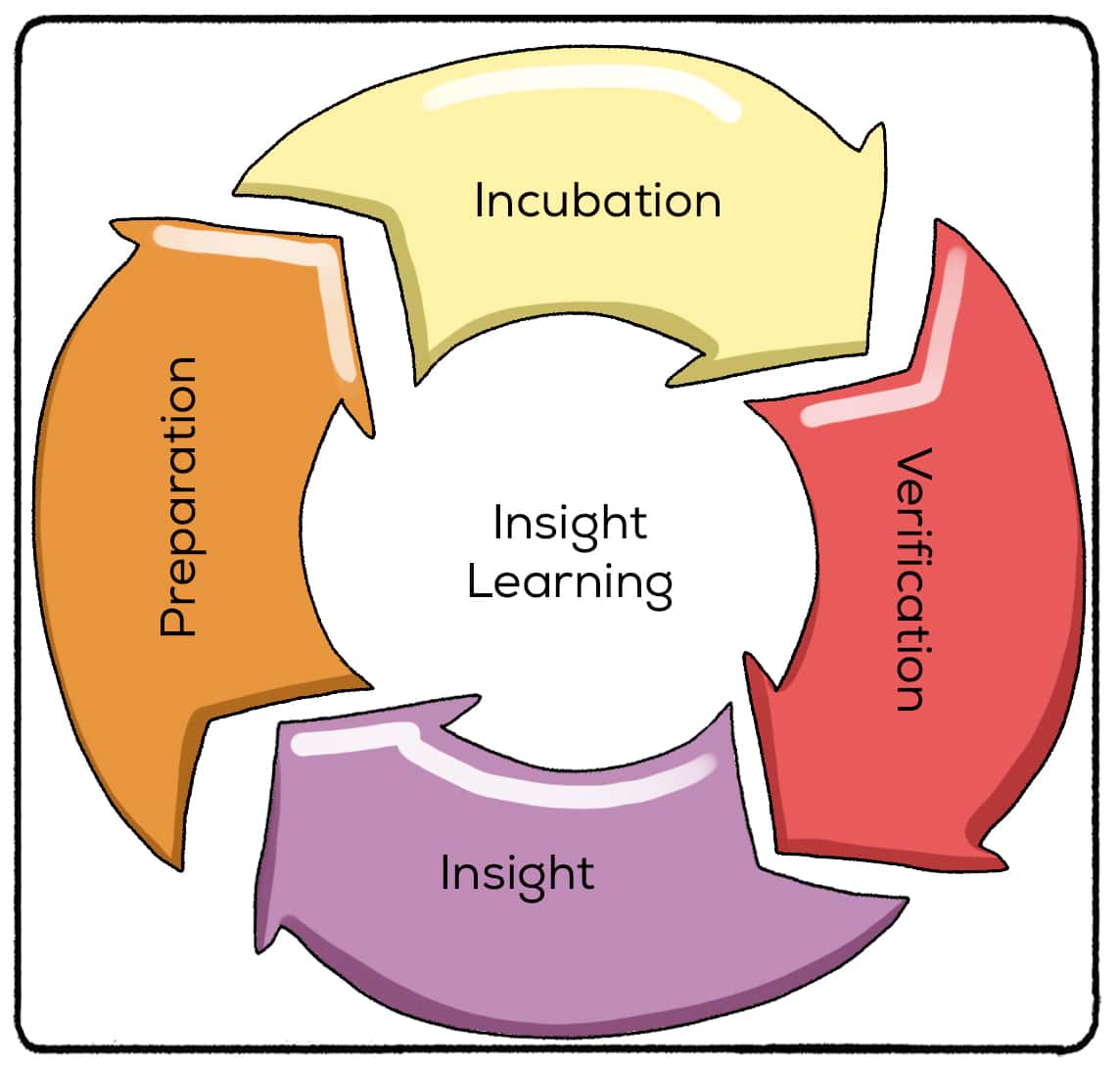

- Incubation: After struggling with the problem, the learner steps away from it. During this period, subconscious processing may occur, allowing the learner’s mind to work on the problem without direct focus.

- Illumination: This is the “aha” moment where the learner suddenly understands the solution or sees the problem in a new light. This realization often comes unexpectedly and leads to a clear understanding of the solution.

- Verification: The learner tests the newfound solution to ensure it works in practice. This step may involve applying the solution to the problem or related situations to confirm its validity.

- Application: The learner applies the insight to similar problems, demonstrating the transfer of knowledge and reinforcing the understanding gained through the insight.

Comparison with Behaviorism

Köhler’s Insight Learning Theory is the opposite of behaviorist theories of learning, especially those of Edward Thorndike and B.F. Skinner. Behaviorism is about learning through direct interaction with the environment, often through trial and error, reinforcement and punishment. According to this view learning is a gradual process and behaviors are shaped over time through repeated associations of stimuli and responses.

Thorndike’s Law of Effect says that behaviors followed by satisfying consequences will be repeated and those followed by discomfort will not be. Köhler’s insight learning says complex problem solving can occur without repeated attempts or external reinforcements. The learner has an “aha” moment when they restructure the problem in their mind and suddenly have the solution.

Educational Applications

Köhler’s Insight Learning Theory has big implications for education as it moves the focus from rote learning and memorization to critical thinking and problem solving. The theory says:

- Emphasize Understanding Over Repetition: Education should be about comprehension and being able to apply concepts in new situations. Teachers can facilitate this by guiding students to see the connections between ideas rather than just recalling isolated facts.

- Create a Supportive Learning Environment: Köhler’s work shows that learners need time and space to reflect and mentally process problems. Classrooms should be designed to be supportive where students can explore, experiment and arrive at solutions in their own time.

Transfer of Learning : Since insight learning is about transferring knowledge to new situations, teachers can design lessons where students apply what they have learned to new scenarios. This reinforces deep understanding and long term retention of concepts.

How Does Insight Learning Theory Relate to Problem-Based Learning?

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is an instructional approach that engages learners in solving real-world problems. In PBL, students are presented with a problem, and they work collaboratively to find solutions by researching, discussing, and reflecting. This approach aligns well with Köhler’s Insight Learning Theory in several ways:

- Emphasis on Problem-Solving : Both Insight Learning and PBL focus on the ability to solve problems, not through memorization or rote learning, but by understanding the structure of the problem. Just as Köhler’s chimpanzees demonstrated an “aha” moment, learners in a PBL environment are encouraged to experience similar moments of clarity when they figure out solutions.

- Cognitive Restructuring: In both theories, learning occurs when individuals can restructure their understanding of a problem. In PBL, students are asked to approach complex, ill-structured problems, which require them to analyze, reflect, and mentally organize information before arriving at a solution, mirroring the insight process in Köhler’s experiments.

- Active and Independent Learning: PBL encourages students to be active participants in their learning process, engaging deeply with the material to solve problems. This promotes independent thinking, just as insight learning emphasizes the learner’s internal cognitive processes rather than external rewards or guidance.

- Transfer of Learning: Insight Learning suggests that once a learner solves a problem through insight, they can apply this solution to similar problems. In PBL, students are often required to take what they’ve learned in one context and transfer that knowledge to new, unfamiliar situations, reinforcing the deep understanding necessary for insight.

- Minimizing Trial and Error: PBL encourages a thoughtful, reflective approach to problem-solving, moving away from the trial-and-error strategies common in behaviorist models. This aligns with insight learning, where individuals don’t rely on repeated attempts but instead restructure their thinking to grasp the solution.

Criticisms of Insight Learning

Köhler’s insight theory has stood the test of time but it’s not without its criticisms. Here are some of the main issues:

- Lack of Generalizability: Many of Köhler’s experiments were done with chimpanzees and while we share some similarities with them, the generalizability to all learning situations in humans has been questioned. Critics argue humans especially children may not always process information the same way Köhler’s chimpanzees do.

- Ignoring Incremental Learning: Insight learning downplays the role of gradual incremental learning which is common in many learning situations. Trial and error and conditioning are part of how we learn especially in situations that require skill development.

- Limited Focus on Individual Differences: Köhler’s theory doesn’t fully account for individual differences in learning. Factors like prior knowledge, cognitive abilities and emotional states may affect the likelihood of insight but these are not fully covered in the theory.

- Replicability Issues: Some of Köhler’s experiments have reproducibility problems, subsequent studies found inconsistent results when they tried to replicate the chimpanzee problem solving experiments.

Legacy and Impact on Modern Psychology

Despite the limitations, Köhler’s Insight Learning Theory has had a big impact on modern psychology, especially in cognitive psychology and educational theory. The idea that learning can happen through sudden cognitive epiphanies challenged the behaviourist views of the early 20th century and laid the groundwork for future research into human thinking.

Köhler’s holistic approach to problem solving has influenced modern education, especially the constructivist learning models which focus on active engagement and knowledge construction. His work also led to cognitive psychology, the field that studies perception, memory and problem solving.

Problem based learning (PBL) and inquiry based learning in modern education can be seen as an extension of Köhler’s theories as they encourage students to explore, reflect and arrive at insights rather than passively receive information.

Wolfgang Köhler’s Insight Learning Theory introduced a new way of thinking about learning. By showing the cognitive processes that lead to sudden problem solving breakthroughs, Köhler provided a framework that differed from behaviourist models, he emphasized understanding over conditioning. His experiments with chimpanzees, especially Sultan, showed that animals (and by extension humans) can solve problems by mentally reorganising situations rather than through trial and error.

The educational implications still hold true, a learning environment that encourages critical thinking, problem solving and understanding. Despite the limitations and criticisms of Köhler’s findings, his work has left a lasting impact on both psychology and education, how we understand the cognitive processes of learning. As we continue to dig into the human mind, Köhler’s Insight Learning Theory is still a valuable addition to how we learn and solve problems in new ways.

Discover more from Educational Psyche

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

By Dr. Dev Arora

Hey there! I'm Dev, and let me tell you a bit about myself. Education has been my passion since I was a kid, and I've dedicated my life to teaching and learning.

Related Post

Ivan pavlov’s classical conditioning theory and its 10 implications, the psychology of learning: 5 key factors influncing learning, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Unlock Personality: 4 Theories of Hippocrates, Kretschmer, Sheldon, Jung for effective teaching

Gifted children: a comprehensive guide to identification and support them in 5 ways, supporting education for special children: unlock 10 types of special children, unlock mentally deficient child | 5 key strategies for teaching mentally restarted children.

This brief excerpt on Kohler's research is from the book: The Animal Mind by J.L Gould & C. G. Gould Wolfgang Kohler, a psychologist trained at the University of Berlin, was working at a primate research facility maintained by the Prussian Academy of Sciences in the Canary Islands when the First World War broke out. Marooned there, he had at his disposal a large outdoor pen and nine chimpanzees of various ages. The pen, described by Kohler as a playground, was provided with a variety of objects including boxes, poles, and sticks, with which the primates could experiment. Kohler constructed a variety of problems for the chimps, each of which involved obtaining food that was not directly accessible. In the simplest task, food was put on the other side of a barrier. Dogs and cats in previous experiments had faced the barrier in order to reach the food, rather than moving away from the goal to circumvent the barrier. The chimps, however, presented with an apparently analogous situation, set off immediately on the circuitous route to the food. It is important to note that the dogs and cats that had apparently failed this test were not necessarily less intelligent than the chimps. The earlier experiments that psychologists had run on dogs and cats differed from Kohler's experiments on chimps in two important ways. First, the barriers were not familiar to the dogs and cats, and thus there was no opportunity for using latent learning, whereas the chimps were well acquainted with the rooms used in Kohler's tests. Second, whereas the food remained visible in the dog and cat experiments, in the chimp test the food was tossed out the window (after which the window was shut) and fell out of sight. Indeed, when Kohler tried the same test on a dog familiar with the room, the animal (after proving to itself that the window was shut), took the shortest of the possible indirect routes to the unseen food. The ability to select an indirect (or even novel) route to a goal is not restricted to chimps, cats, and dogs. At least some insects routinely perform similar feats. The cognitive processing underlying these abilities will become clearer when we look at navigation by chimps in a later chapter. For now, the point is that the chimpanzees' abilities to plan routes are not as unique as they appeared at the time. Some of the other tests that Kohler is known for are preserved on film. In a typical sequence, a chimp jumps fruitlessly at bananas that have been hung out of reach. Usually, after a period of unsuccessful jumping, the chimp apparently becomes angry or frustrated, walks away in seeming disgust, pauses, then looks at the food in what might be a more reflective way, then at the toys in the enclosure, then back at the food, and then at the toys again. Finally the animal begins to use the toys to get at the food. The details of the chimps' solutions to Kohler's food-gathering puzzle varied. One chimp tried to shinny up a toppling pole it had poised under the bananas; several succeeded by stacking crates underneath, but were hampered by difficulties in getting their centers of gravity right. Another chimp had good luck moving a crate under the bananas and using a pole to knock them down. The theme common to each of these attempts is that, to all appearances, the chimps were solving the problem by a kind of cognitive trial and error, as if they were experimenting in their minds before manipulating the tools. The pattern of these behaviors--failure, pause, looking at the potential tools, and then the attempt--would seem to involve insight and planning, at least on the first occasion. Photos and captions from The Mentality of Apes click on each image to see larger version Chica on the jumping stick Grande on an insecure construction Sulton making a double-stick Konsul, Grande, Sultona and Chica building Grande achieves a four-story structure Read Kohler's Introduction to the Mentality of Apes Kohler's objections to Thorndike's approach to Animal Intelligence Questions about Kohler's conclusions: by P. Schiller's later work looking at the same issue Kenneth Spence's take on this general issue by R. Epstein's work on "insight" in pigeons Back to Main History Page

Wolfgang Köhler's The Mentality of Apes and the animal psychology of his time

Affiliation.

- 1 Universidad de Sevilla (Spain).

- PMID: 26055050

- DOI: 10.1017/sjp.2014.70

In 1913, the Anthropoid Station for psychological and physiological research in chimpanzees and other apes was founded by the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (Berlin) near La Orotava, Tenerife. Eugene Teuber, its first director, began his work at the Station with several studies of anthropoid apes' natural behavior, particularly chimpanzee body language. In late 1913, the psychologist Wolfgang Köhler, the second and final director of the Station, arrived in Tenerife. During his stay in the Canary Islands, Köhler conducted a series of studies on intelligent behavior in chimpanzees that would become classics in the field of comparative psychology. Those experiments were at the core of his book Intelligenzprüfungen an Menschenaffen (The Mentality of Apes), published in 1921. This paper analyzes Köhler's experiments and notions of intelligent behavior in chimpanzees, emphasizing his distinctly descriptive approach to these issues. It also makes an effort to elucidate some of the theoretical ideas underpinning Köhler's work. The ultimate goal of this paper is to assess the historical significance of Köhler's book within the context of the animal psychology of his time.

Publication types

- Historical Article

- Behavior, Animal

- History, 20th Century

- Hominidae / psychology

- Intelligence

- Pan troglodytes / psychology

- Psychology, Comparative / history*

Personal name as subject

- Wolfgang Köhler

Köhler, Wolfgang (1887–1967)

- Reference work entry

- pp 1696–1698

- Cite this reference work entry

- Norbert M. Seel 2

433 Accesses

Wolfgang Köhler was born in 1887 in Reval, Estonia, and grew up in Wolfenbüttel, Germany. Köhler studied philosophy, science, and psychology at the Universities of Tübingen, Bonn, and Berlin. One of his teachers in science was Max Planck. He studied psychology with Carl Stumpf and earned his Ph.D. from the University of Berlin in psycho-acoustics in 1909. Then he moved to Frankfurt am Main, where he collaborated with Max Wertheimer and Kurt Koffka from 1910 to 1913, working on the foundations of Gestalt theory. From 1913 to 1920, Köhler served as Director of the Anthropoid Institute of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Tenerife (Canary Islands), where he conducted research with animals on insightful learning. In 1921, he was appointed to the most prestigious position in German psychology, Director of the Psychological Institute at the Friedrich-Wilhelm University of Berlin, which became the center of Gestalt psychology for the next 14 years. Like many other cultural...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Boring, E. G. (1950). A history of experimental psychology (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Henle, M. (1978). One man against the Nazis – Wolfgang Köhler. The American Psychologist, 33 , 939–944.

Article Google Scholar

Hergenhahn, B. R. (2009). An introduction to the history of psychology (6th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth.

Hothersall, D. (1995). History of psychology . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Köhler, W. (1917/1925). The mentality of apes . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Köhler, W. (1929/1970). Gestalt psychology: An introduction to new concepts in modern psychology . New York: Liveright.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Education, University of Freiburg, Rempartstr. 11, 3. OG, Freiburg, 79098, Germany

Prof. Norbert M. Seel ( Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Norbert M. Seel .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Education, University of Freiburg, 79085, Freiburg, Germany

Norbert M. Seel

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Seel, N.M. (2012). Köhler, Wolfgang (1887–1967). In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_1487

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_1487

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-1427-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-1428-6

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Insight Learning (Definition+ 4 Stages + Examples)

Have you ever been so focused on a problem that it took stepping away for you to figure it out? You can’t find the solution when you’re looking at all of the moving parts, but once you get distracted with something else - “A-ha!” you have it.

When a problem cannot be solved by applying an obvious step-by-step solving sequence, Insight learning occurs when the mind rearranges the elements of the problem and finds connections that were not obvious in the initial presentation of the problem. People experience this as a sudden A-ha moment.

Humans aren’t the only species that have these “A-ha” moments. Work with other species helped psychologists understand the definition and stages of Insight Learning. This video is going to break down those stages and how you can help to move these “a-ha” moments along.

What Is Insight Learning?

Insight learning is a process that leads to a sudden realization regarding a problem. Often, the learner has tried to understand the problem, but steps away before the change in perception occurs. Insight learning is often compared to trial-and-error learning, but it’s slightly different.

Rather than just trying different random solutions, insight learning requires more comprehension. Learners aim to understand the relationships between the pieces of the puzzle. They use patterns, organization, and past knowledge to solve the problem at hand.

Is Insight Learning Only Observed In Humans?

Humans aren’t the only species that learn with insight. Not all species use this process - just the ones that are closest to us intellectually. Insight learning was first discovered not by observing humans, but by observing chimps.

In the early 1900s, Wolfgang Köhler observed chimpanzees as they solved problems. Köhler’s most famous subject was a chimp named Sultan. The psychologist gave Sultan two sticks of different sizes and placed a banana outside of Sultan’s cage. He watched as Sultan looked at the sticks and tried to reach for the banana with no success. Eventually, Sultan gave up and got distracted. But it was during this time that Köhler noticed Sultan having an “epiphany.” The chimp went back to the sticks, placed one inside of the other, and used this to bring the banana to him.

Since Köhler’s original observations took place, psychologists looked deeper into the insight process and when you are more likely to experience that “a-ha” moment. There isn’t an exact science to insight learning, but certain theories suggest that some places are better for epiphanies than others.

Four Stages of Insight Learning

But how does insight learning happen? Multiple models have been developed, but the four-stage model is the most popular. The four stages of insight learning are preparation, incubation, insight, and verification.

Preparation

The process begins as you try to solve the problem. You have the materials and information in front of you and begin to make connections. Although you see the relationships between the materials, things just haven’t “clicked” yet. This is the stage where you start to get frustrated.

During the incubation period, you “give up” for a short period of time. Although you’ve abandoned the project, your brain is still making connections on an unconscious level.

When the right connections have been made in your mind, the “a-ha” moment occurs. Eureka! You have an epiphany!

Verification

Now, you just have to make sure that your epiphany is right. You test out your solution and hopefully, it works! This is a great moment in your learning journey. The connections you make solving this problem are likely to help you in the future.

Examples of Insight Learning

Insight learning refers to the sudden realization or understanding of a solution to a problem without the need for trial-and-error attempts. It's like a "light bulb" moment when things suddenly make sense. Here are some examples of insight learning:

- The Matchstick Problem : Realizing you can light a match and use it to illuminate a dark room instead of fumbling around in the dark.

- Sudoku Puzzles : Suddenly seeing a pattern or number placement that you hadn't noticed before, allowing you to complete the puzzle.

- The Two Rope Problem : In an experiment, a person is given two ropes hanging from the ceiling and is asked to tie them together. The solution involves swinging one rope like a pendulum and grabbing it with the other.

- Opening Jars : After struggling to open a jar, you remember you can tap its lid lightly or use a rubber grip to make it easier.

- Tangram Puzzles : Suddenly realizing how to arrange the geometric pieces to complete the picture without any gaps.

- Escape Rooms : Having an "aha" moment about a clue that helps you solve a puzzle and move to the next challenge.

- The Nine Dot Problem : Connecting all nine dots using only four straight lines without lifting the pen.

- Cooking : Realizing you can soften butter quickly by grating it or placing it between two sheets of parchment paper and rolling it.

- Math Problems : Suddenly understanding a complex math concept or solution method after pondering it for a while.

- Guitar Tuning : Realizing you can use the fifth fret of one string to tune the next string.

- Traffic Routes : Discovering a faster or more efficient route to your destination without using a GPS.

- Packing Suitcases : Figuring out how to fit everything by rolling clothes or rearranging items in a specific order.

- The Crow and the Pitcher : A famous Aesop's fable where a thirsty crow drops pebbles into a pitcher to raise the water level and drink.

- Computer Shortcuts : Discovering a keyboard shortcut that makes a task you frequently do much quicker.

- Gardening : Realizing you can use eggshells or coffee grounds as a natural fertilizer.

- Physics Problems : After struggling with a concept, suddenly understanding the relationship between two variables in an equation.

- Art : Discovering a new technique or perspective that transforms your artwork.

- Sports : Realizing a different way to grip a tennis racket or baseball bat that improves your game.

- Language Learning : Suddenly understanding the grammar or pronunciation rule that was previously confusing.

- DIY Projects : Figuring out a way to repurpose old items in your home, like using an old ladder as a bookshelf.

Where Is the Best Place to Have an Epiphany?

But what if you want to have an epiphany? You’re stuck on a problem and you can’t take it anymore. You want to abandon it, but you’re not sure what you should do for this epiphany to take place. Although an “a-ha” moment isn’t guaranteed, studies suggest that the following activities or places can help you solve a tough problem.

The Three B’s of Creativity

Creativity and divergent thinking are key to solving problems. And some places encourage creativity more than others. Researchers believe that you can kickstart divergent thinking with the three B’s: bed, bath, and the bus.

Sleep

“Bed” might be your best bet out of the three. Studies show that if you get a full night’s sleep, you will be twice as likely to solve a problem than if you stay up all night. This could be due to the REM sleep that you get throughout the night. During REM sleep , your brain is hard at work processing the day’s information and securing connections. Who knows - maybe you’ll dream up the answer to your problems tonight!

Meditation

The word for “insight” in the Pali language is vipassana. If you have ever been interested in meditation , you might have seen this word before. You can do a vipassana meditation at home, or you can go to a 10-day retreat. These retreats are often silent and are set up to cultivate mind-body awareness.

You certainly don’t have to sign up for a 10-day silent retreat to solve a problem that is bugging you. (Although, you may have a series of breakthroughs!) Try meditating for 20 minutes at a time. Studies show that this can increase the likelihood of solving a problem.

Laugh!

How do you feel when you have an epiphany? Good, right? The next time you’re trying to solve a problem, check in with your emotions. You are more likely to experience insight when you’re in a positive mood. Positivity opens your mind and gives your mind more freedom to explore. That exploration may just lead you to your solution.

Be patient when you’re trying to solve problems. Take breaks when you need to and make sure that you are taking care of yourself. This approach will help you solve problems faster and more efficiently!

Insight Vs. Other Types Of Learning.

Learning by insight is not learning by trial and error, nor by observation and imitation. Learning by insight is a learning theory accepted by the Gestalt school of psychology, which disagrees with the behaviorist school, which claims that all learning occurs through conditioning from the external environment.

Gestalt is a German word that approximately translates as ‘an organized whole that has properties and elements in addition to the sum of its parts .’ By viewing a problem as a ‘gestalt’ , the learner does not simply react to whatever she observes at the moment. She also imagines elements that could be present but are not and uses her imagination to combine parts of the problem that are presently not so combined in fact.

Insight Vs. Trial And Error Learning

Imagine yourself in a maze-running competition. You and your rivals each have 10 goes. The first one to run the maze successfully wins $500. You may adopt a trial-and-error strategy, making random turning decisions and remembering whether those particular turns were successful or not for your next try. If you have a good memory and with a bit of luck, you will get to the exit and win the prize.

Completing the maze through trial and error requires no insight. If you had to run a different maze, you would have no advantage over running previous mazes with different designs. You have now learned to run this particular maze as predicted by behaviorist psychologists. External factors condition your maze running behavior. The cash prize motivates you to run the maze in the first place. All maze dead ends act as punishments , which you remember not to repeat. All correct turns act as rewards , which you remember to repeat.

If you viewed the maze running competition as a gestalt, you might notice that it doesn't explicitly state in the competition rules that you must run along the designated paths to reach the exit.

Suppose you further noticed that the maze walls were made from cardboard. In that case, you may combine those 2 observations in your imagination and realize that you could just punch big holes in the walls or tear them down completely, to see around corners and directly run to the now visible exit.

Insight Vs. Learning Through Observation, Imitation, And Repetition

Observation, imitation, and repetition are at the heart of training. The violin teacher shows you how to hold your bow correctly; you practice your scales countless times before learning to play a sonata from Beethoven flawlessly. Mastering a sport or a musical instrument rarely comes from a flash of insight but a lot of repetition and error correction from your teacher.

Herbert Lawford, the Scottish tennis player, and 1887 Wimbledon champion, is credited for being the first player to play a topspin. Who could have taught it to him? Who could he have imitated? One can only speculate since no player at that time was being coached on how to hit topspin.

He could have only learned to play a topspin by having a novel insight. One possibility is that he played one by accident during training, by mistakenly hitting the ball at a flatter angle than normal. He could then have observed that his opponent was disorientated by the flatter and quicker bounce of the ball and realized the benefit of his ‘mistake’ .

Behaviorist theories of learning can probably explain how most successful and good tennis players are produced, but you need a Gestalt insight learning theory to explain Herbert Lawford.

Another interesting famous anecdote illustrating insight learning concerned Carl Friedrich Gauss when he was a 7-year-old pupil at school. His mathematics teacher seems to have adopted strict behaviorism in his teaching since the original story implies that he beat students with a switch.

One day the teacher set classwork requiring the students to add up all the numbers from 1 to 100. He expected his pupils to perform this calculation in how they were trained. He expected it to be a laborious and time-consuming task, giving him a long break. In just a few moments, young Gauss handed in the correct answer after having to make at most 2 calculations, which are easy to do in your head. How did he do it? Gauss saw the arithmetic sequence as a gestalt instead of adding all the numbers one at a time: 1+2+3+4…. +99+100 as he expected.

He realized that by breaking this sequence in half at 50, then snaking the last number (100) under the first number (1), and then adding the 2 halves of the arithmetic sequence like so:

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + …………. + 48 + 49 + 50

100 + 99 + 98 + 97 + 96 + …………... + 53 + 52 + 51

101 + 101 + 101 + 101 + 101 + ……………. + 101 + 101 + 101

Arranged in this way, each number column adds up to 101, so all Gauss needed to do was calculate 50 x 101 = 5050.

Can Major Scientific Breakthroughs be made through observation and experiment alone?

Science is unapologetically an evidence-based inquiry. Observations, repeatable experiments, and hard, measurable data must support theories and explanations.

Since countless things can be observed and comparisons made, they cannot be done randomly for observations and experiments to advance knowledge. They must be guided by a good question and a testable hypothesis. Before performing actual experiments and observations, scientists often first perform thought experiments . They think of ideal situations by imagining ways things could be or imaging away things that are.

Atoms were talked about long before electron microscopes could observe them. How could atoms be seriously discussed in ancient Greece long before the discoveries of modern chemistry? Pre-Socratic philosophers were puzzled by a purely philosophical problem, which they termed the problem of the one and many .

People long observed that the world was made of many different things that didn't remain static but continuously changed into other various things. For example, a seed different from a tree changed into a tree over time. Small infants change into adults yet remain the same person. Boiling water became steam, and frozen water became ice.

Observing all of this in the world, philosophers didn’t simply take it for granted and aimed to profit from it practically through stimulus-response and trial and error learning. They were puzzled by how the world fit together as a whole.

To make sense of all this observable changing multiplicity, one needed to imagine an unobservable sameness behind it all. Yet, there is no obvious or immediate punishment or reward. Therefore, there seems to be no satisfying behaviorist reason behind philosophical speculations.

Thinkers such as Empedocles and Aristotle made associations between general properties in the world wetness, dryness, temperature, and phases of matter as follows:

- Earth : dry, cold

- Fire: dry, hot

- Water: wet, cold

- Air: hot or wet, depending on whether moisture or heat prevails in the atmosphere.

These 4 primitive elements transformed and combined give rise to the diversity we see in the world. However, this view was still too sensually based to provide the world with sought-for coherence and unity. How could a multiplicity of truly basic stuff interact? Doesn't such an interaction presuppose something more fundamental in common?

The ratio of these 4 elements was thought to affect the properties of things. Stone contained more earth, while a rabbit had more water and fire, thus making it soft and giving it life. Although this theory correctly predicted that seemingly basic things like stones were complex compounds, it had some serious flaws.

For example, if you break a stone in half many times, the pieces never resemble fire, air, water, or earth.

To account for how different things could be the same on one level and different on another level, Leucippus and his student Democritus reasoned that all things are the same in that they were made from some common primitive indivisible stuff but different due to the different ways or patterns in which this indivisible stuff or atoms could be arranged.

For atoms to be able to rearrange and recombine into different patterns led thinkers to the insight that if the atom idea was true, then logically, there had to be free spaces between the atoms for them to shift into. They had to imagine a vacuum, another phenomenon not directly observable since every nook and cranny in the world seems to be filled with some liquid, solid, or gas.

This ancient notion of vacuum proved to be more than just a made-up story since it led to modern practical applications in the form of vacuum cleaners and food vacuum packing.

This insight that atoms and void exist makes no sense from a behaviorist learning standpoint. It cannot be explained in terms of stimulus-response or environmental conditioning and made no practical difference in the lives of ancient Greeks.

For philosophers to feel compelled to hold onto notions, which at the time weren’t directly useful, it suggests that they must have felt some need to understand the universe as an intelligible ‘gestalt’ One may even argue that the word Cosmos, from the Greek word Kosmos, which roughly translates to ‘harmonious arrangement’ is at least a partial synonym.

The Historical Development Of The Theory of Insight Learning

Wolfgang Kohler , the German gestalt psychologist, is credited for formulating the theory of insight learning, one of the first cognitive learning theories. He came up with the theory while first conducting experiments in 1913 on 7 chimpanzees on the island of Tenerife to observe how they learned to solve problems.

In one experiment, he dangled a banana from the top of a high cage. Boxes and poles were left in the cage with the chimpanzees. At first, the chimps used trial and error to get at the banana. They tried to jump up to the banana without success. After many failed attempts, Kohler noticed that they paused to think for a while.

After some time, they behaved more methodically by stacking the boxes on top of each other, making a raised platform from which they could swipe at the banana using the available poles. Kohler believed that chimps, like humans, were capable of experiencing flashes of insight, just like humans.

In another experiment, he placed a peanut down a long narrow tube attached to the cage's outer side. The chimpanzee tried scooping the peanut out with his hand and fingers, but to no avail, since the tube was too long and narrow. After sitting down to think, the chimp filled its mouth with water from a nearby water container in the cage and spat it into the tube.

The peanut floated up the tube within the chimp's reach. What is essential is that the chimp realized it could use water as a tool in a flash of insight, something it had never done before or never shown how to do . Kohler's conclusions contrasted with those of American psychologist Edward Thorndike , who, years back, conducted learning experiments on cats, dogs, and monkeys.

Through his experiments and research, Thorndike concluded that although there was a vast difference in learning speed and potential between monkey dogs and cats, he concluded that all animals, unlike humans, are not capable of genuine reasoned thought. According to him, Animals can only learn through stimulus-response conditioning, trial and error, and solve problems accidentally.

Kohler’s 4 Stage Model Of Insight Learning

From his observations of how chimpanzees solve complex problems, he concluded that the learning process went through the following 4 stages:

- Preparation: Learners encounter the problem and begin to survey all relevant information and materials. They process stimuli and begin to make connections.

- Incubation: Learners get frustrated and may even seem to observers as giving up. However, their brains carry on processing information unconsciously.

- Insight: The learner finally achieves a breakthrough, otherwise called an epiphany or ‘Aha’ moment. This insight comes in a flash and is often a radical reorganization of the problem. It is a discontinuous leap in understanding rather than continuous with reasoning undertaken in the preparation phase.

- Verification: The learner now formally tests the new insight and sees if it works in multiple different situations. Mathematical insights are formally proved.

The 2 nd and 3 rd stages of insight learning are well described in anecdotes of famous scientific breakthroughs. In 1861, August Kekulé was contemplating the structure of the Benzene molecule. He knew it was a chain of 6 carbon atoms attached to 6 hydrogen atoms. Still, He got stuck (incubation phase) on working out how they could fit together to remain chemically stable.

He turned away from his desk and, facing the fireplace, fell asleep. He dreamt of a snake eating its tail and then spinning around. He woke up and realized (insight phase) that these carbon-hydrogen chains can close onto themselves to form hexagonal rings. He then worked out the consequences of his new insight on Benzene rings. (Verification phase)

Suitably prepared minds can experience insights while observing ordinary day-to-day events. Many people must have seen apples fall from trees and thought nothing of it. When Newton saw an apple fall, he connected its fall to the action of the moon. If an unseen force pulls the apple from the tree top, couldn't the same force extends to the moon? This same force must be keeping the moon tethered in orbit around the earth, keeping it from whizzing off into space. Of course, this seems counterintuitive because if the moon is like the apple, should it not be crashing down to earth?

Newton's prepared mind understood the moon to be continuously falling to earth around the horizon's curve. Earth's gravitational pull on the moon balanced its horizontal velocity tangential to its orbit. If the apple were shot fast enough over the horizon from a cannon, it too, like the moon, would stay in orbit.

So, although before Newton, everyone was aware of gravity in a stimulus-response kind of way and even made practical use of it to weigh things, no one understood its universal implications.

Applying Insight Learning To The Classroom

The preparation-incubation-insight- verification cycle could be implemented by teachers in the classroom. Gestalt theory predicts that students learn best when they engage with the material; they are mentally prepared for age, and maturity, having had experiences enabling them to relate to the material and having background knowledge that allows them to contextualize the material. When first presenting content they want to teach the students, teachers must make sure students are suitably prepared to receive the material, to successfully go through the preparation stage of learning.

Teachers should present the material holistically and contextually. For example, when teaching about the human heart, they should also teach where it is in the human body and its functional importance and relationship to other organs and parts of the body. Teachers could also connect other fields, such as comparing hearts to mechanical pumps.

Once the teacher has imparted sufficient background information to students, they should set a problem for their students to solve independently or in groups. The problem should require the students to apply what they have learned in a new way and make novel connections not explicitly made by the teacher during the lesson.

However, they must already know and be familiar with all the material they need to solve the problem. Students must be allowed to fumble their way to a solution and make many mistakes , as this is vital for the incubation phase. The teacher should resist the temptation to spoon-feed them. Instead, teachers should use the Socratic method to coax the students into arriving at solutions and answers themselves.

Allowing the students to go through a sufficiently challenging incubation phase engages all their higher cognitive functions, such as logical and abstract reasoning, visualization, and imagination. It also habituates them to a bit of frustration to build the mental toughness to stay focused.

It also forces their brains to work hard in processing combining information to sufficiently own the insights they achieve, making it more likely that they will retain the knowledge they gained and be able to apply it across different contexts.

Once students have written down their insights and solutions, the teacher should guide them through the verification phase. The teacher and students need to check and test the validity of the answers. Solutions should be checked for errors and inconsistencies and checked against the norms and standards of the field.

However, one should remember that mass education is aimed at students of average capacity and that not all students are always equally capable of learning through insight. Also, students need to be prepared to gain the ability and potential to have fruitful insights.

Learning purely from stimulus-response conditioning is insufficient for progress and major breakthroughs to be made in the sciences. For breakthroughs to be made, humans need to be increasingly capable of higher and higher levels of abstract thinking.

However, we are not all equally capable of having epiphanies on the cutting edge of scientific research. Most education aims to elevate average reasoning, knowledge, and skill acquisition. For insight, learning must build on rather than replace behaviorist teaching practices.

Related posts:

- The Psychology of Long Distance Relationships

- Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI Test)

- Operant Conditioning (Examples + Research)

- Variable Interval Reinforcement Schedule (Examples)

- Concrete Operational Stage (3rd Cognitive Development)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Operant Conditioning

Classical Conditioning

Observational Learning

Latent Learning

Experiential Learning

The Little Albert Study

Bobo Doll Experiment

Spacing Effect

Von Restorff Effect

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

His experiments with chimpanzees, especially Sultan, showed that animals (and by extension humans) can solve problems by mentally reorganising situations rather than through trial and error. The educational implications still hold true, a learning environment that encourages critical thinking, problem solving and understanding.

The pen, described by Kohler as a playground, was provided with a variety of objects including boxes, poles, and sticks, with which the primates could experiment. Kohler constructed a variety of problems for the chimps, each of which involved obtaining food that was not directly accessible.

This paper analyzes Köhler's experiments and notions of intelligent behavior in chimpanzees, emphasizing his distinctly descriptive approach to these issues. It also makes an effort to elucidate some of the theoretical ideas underpinning Köhler's work.

Köhler used four chimpanzees in his experiments, Chica, Grande, Konsul, and Sultan. In one experiment, Kohler placed bananas outside Sultan’s cage and two bamboo sticks inside his cage. Neither stick was long enough to reach the bananas, so the only way to reach them was to put the sticks together.

According to Köhler’s interpretation, the solution depended on a perceptual reorganization of the chimpanzee’s world—seeing a pole as a rake, or a series of boxes as a ladder—rather than on forming any new associations. But subsequent experimental analysis has cast some doubts on Köhler’s claims.

Wolfgang Koehler demonstrated that chimpanzees could solve problems by applying insight. His research showed that the intellectual gap between humans and chimpanzees was much narrower than previously thought.

The experiments consisted of placing chimpanzees in an enclosed area and presenting them with a desired object that was out of reach. In one experiment, Köhler placed bananas outside Sultan's cage and two bamboo sticks inside his cage which needed to be put together to reach the bananas.

Wolfgang Koehler demonstrated that chimpanzees could solve problems by applying insight. His research showed that the intellectual gap between humans and chimpanzees was much narrower than...

Psychology textbooks frequently present Wolfgang Kohler's two-stick experiment with chimpanzees as having demonstrated insight in learning. Studies that replicated Kohler's work support his findings but not his interpretation in terms of insightful solution.

Wolfgang Kohler, the German gestalt psychologist, is credited for formulating the theory of insight learning, one of the first cognitive learning theories. He came up with the theory while first conducting experiments in 1913 on 7 chimpanzees on the island of Tenerife to observe how they learned to solve problems.