- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

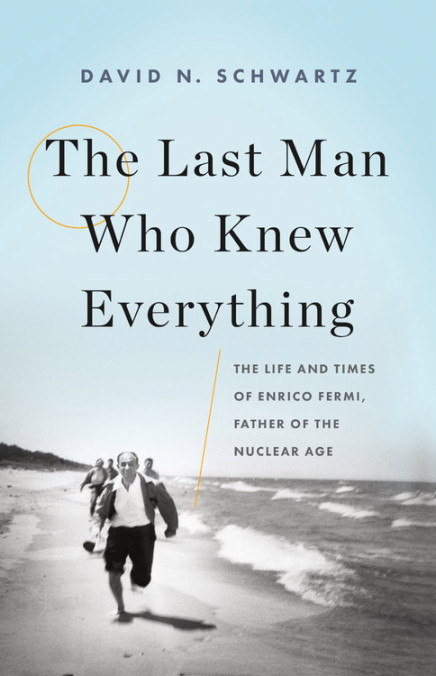

THE LAST MAN WHO KNEW EVERYTHING

The life and times of enrico fermi, father of the nuclear age.

by David N. Schwartz ‧ RELEASE DATE: Dec. 5, 2017

A rewarding, expert biography of a giant of the golden age of physics.

A fine life of the scientist “who knew everything about physics, the study of matter, energy, time, and their relationship.”

Never a media darling like Einstein or Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi (1901-1954) is now barely known to the public, but few scientists would deny that he was among the most brilliant physicists of his century. A lucid writer who has done his homework, Schwartz ( NATO’s Nuclear Dilemma , 1983), whose father won a Nobel Prize in physics, delivers a thoroughly enjoyable, impressively researched account. The son of a middle-class Italian family, Fermi was a prodigy. As an adolescent, he absorbed textbooks in physics and mathematics and obtained perfect grades in those subjects in college. After graduation, he led a team that made Italy, formerly a backwater, a world-class center of physics. In the decade after 1925, Fermi described the weak interaction, one of the four fundamental forces of nature, and perfected neutron bombardment of the atomic nucleus, which produced artificial radioactivity and ultimately nuclear fission and the atomic bomb. After winning the Nobel Prize in physics in 1938, he left Mussolini’s Italy for the United States, where his research indicated that neutrons from uranium fission would lead to a chain reaction releasing enormous energy. Proving this required an actual chain reaction, which he accomplished in 1942 after building the first atomic reactor. He led a section of the Manhattan project, which produced the atomic bomb, and remained a dominant figure until his premature death at 53. Einstein only theorized; Ernest Lawrence only built machines and experimented; Fermi excelled at both besides being a superb teacher universally loved by students. Neither eccentric nor introspective, he kept no diary, so little is known of his inner life, but Schwartz has no qualms about speculating.

Pub Date: Dec. 5, 2017

ISBN: 978-0-465-07292-7

Page Count: 480

Publisher: Basic Books

Review Posted Online: Aug. 27, 2017

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Sept. 15, 2017

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY | GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR

Share your opinion of this book

by Elie Wiesel & translated by Marion Wiesel ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 16, 2006

The author's youthfulness helps to assure the inevitable comparison with the Anne Frank diary although over and above the...

Elie Wiesel spent his early years in a small Transylvanian town as one of four children.

He was the only one of the family to survive what Francois Maurois, in his introduction, calls the "human holocaust" of the persecution of the Jews, which began with the restrictions, the singularization of the yellow star, the enclosure within the ghetto, and went on to the mass deportations to the ovens of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. There are unforgettable and horrifying scenes here in this spare and sombre memoir of this experience of the hanging of a child, of his first farewell with his father who leaves him an inheritance of a knife and a spoon, and of his last goodbye at Buchenwald his father's corpse is already cold let alone the long months of survival under unconscionable conditions.

Pub Date: Jan. 16, 2006

ISBN: 0374500010

Page Count: 120

Publisher: Hill & Wang

Review Posted Online: Oct. 7, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 15, 2006

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | HOLOCAUST | HISTORY | GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | GENERAL HISTORY

More by Elie Wiesel

BOOK REVIEW

by Elie Wiesel ; edited by Alan Rosen

by Elie Wiesel ; illustrated by Mark Podwal

by Elie Wiesel ; translated by Marion Wiesel

THE PURSUIT OF HAPPYNESS

From mean streets to wall street.

by Chris Gardner with Quincy Troupe ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 1, 2006

Well-told and admonitory.

Young-rags-to-mature-riches memoir by broker and motivational speaker Gardner.

Born and raised in the Milwaukee ghetto, the author pulled himself up from considerable disadvantage. He was fatherless, and his adored mother wasn’t always around; once, as a child, he spied her at a family funeral accompanied by a prison guard. When beautiful, evanescent Moms was there, Chris also had to deal with Freddie “I ain’t your goddamn daddy!” Triplett, one of the meanest stepfathers in recent literature. Chris did “the dozens” with the homies, boosted a bit and in the course of youthful adventure was raped. His heroes were Miles Davis, James Brown and Muhammad Ali. Meanwhile, at the behest of Moms, he developed a fondness for reading. He joined the Navy and became a medic (preparing badass Marines for proctology), and a proficient lab technician. Moving up in San Francisco, married and then divorced, he sold medical supplies. He was recruited as a trainee at Dean Witter just around the time he became a homeless single father. All his belongings in a shopping cart, Gardner sometimes slept with his young son at the office (apparently undiscovered by the night cleaning crew). The two also frequently bedded down in a public restroom. After Gardner’s talents were finally appreciated by the firm of Bear Stearns, his American Dream became real. He got the cool duds, hot car and fine ladies so coveted from afar back in the day. He even had a meeting with Nelson Mandela. Through it all, he remained a prideful parent. His own no-daddy blues are gone now.

Pub Date: June 1, 2006

ISBN: 0-06-074486-3

Page Count: 320

Publisher: Amistad/HarperCollins

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 15, 2006

GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | BUSINESS

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Advertisement

Supported by

A Remarkable Man Among Remarkable Men and Women

- Share full article

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

By Richard Rhodes

- Jan. 24, 2018

THE LAST MAN WHO KNEW EVERYTHING The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age By David N. Schwartz Illustrated. 451 pp. Basic Books. $35.

Albert Einstein once remarked that he had sold himself body and soul to science, “being in flight from the I and the we to the it .” Einstein’s transformation followed from and repudiated an early-adolescent phase of intense religiosity. Enrico Fermi, the Italian-American physicist whose long list of achievements includes co-inventing the nuclear reactor , escaped into science as well, but in his case the impetus was traumatic: the sudden death of his beloved older brother, Giulio, during throat surgery when Fermi was 13.

That loss precipitated an intense lifelong privacy and a personal and scientific strategy of quantifying the world. Fermi wielded a six-inch slide rule as we today wield our iPhones, to plumb the essence of events. He ranks high in the second tier of 20th-century physicists, behind figures like Einstein and the Danish theoretician Niels Bohr. There have been other accounts of his life, yet David N. Schwartz’s new portrait, “The Last Man Who Knew Everything,” is the first thorough biography to be published since Fermi’s death 64 years ago in 1954.

Schwartz, the author of “NATO’s Nuclear Dilemmas,” cautions that the record of Fermi’s life is thin: no personal journals, few letters, little more than the testimony of colleagues, family and friends. The biographer was forced to devote most of his effort to Fermi’s work life.

With a subject like Fermi, that restriction is a limit but hardly a loss. When Fermi died of stomach cancer at 53, Hans Bethe, the theorist who taught us how the sun shines, wrote his colleague’s widow, Laura, “There is no one like Enrico, and there will not be another for a hundred years.” Schwartz calls Fermi “the greatest Italian scientist since Galileo.” Add to these tributes that Fermi was a natural leader — charming, gregarious, bursting with energy, easy in command — and one is left wondering why a full biography has been so long delayed.

The American part of Fermi’s life began in 1938. When the Swedish Academy decided to award him that year’s Nobel Prize in Physics for his work with radioactive elements and nuclear reactions, it took the unusual step of having Bohr ask Fermi privately if he could accept it. Adolf Hitler had banned the Nobels in Germany after a German peace activist was awarded the 1935 Peace Prize. In 1938, the academy feared Italy’s Fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, might follow suit. Fermi knew Mussolini was hungry for national honors and told Bohr so.

The advance notice gave the Fermis time to prepare their escape, urgent because Laura was Jewish and Mussolini was promulgating increasingly harsh anti-Semitic laws. The Nobel, worth more than $500,000 today, set up the family in its new country, where a professorship at Columbia University awaited the new laureate. Fatefully, the Fermis sailed from Italy the same week that two Berlin radiochemists discovered nuclear fission .

That discovery was totally unexpected. In spring 1939, working at Columbia with the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard , Fermi set out to answer a crucial question about it. Uranium atoms release a burst of energy when they fission, enough per atom to make a grain of sand visibly jump. But what then? Was there a way to combine those individual fissions, to turn a small burst into a mighty roar?

Szilard, ever-resourceful, acquired hundreds of pounds of black, greasy uranium-oxide powder from a Canadian mining corporation. Fermi and his students packed the powder into pipe-like tin cans and arranged them equally spaced in a circle within a large tank of water mixed with powdered manganese. At the center of the arrangement they placed a neutron source.

Neutrons from the source, slowed down by the water, would penetrate the uranium atoms in the cans and induce fissions. If the fissioning atoms released more neutrons, those “secondary” neutrons would irradiate the manganese. Measuring the radioactivity induced in the manganese would tell Fermi if the fissions were multiplying. If so, then a chain reaction might be possible, one bombarding neutron splitting a uranium atom and releasing two neutrons, those two splitting two other uranium atoms and releasing four, the four releasing eight, and so on in a geometric progression that could potentially produce vast amounts of energy for power — or for an atomic bomb. The experiment worked.

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized a program to build atomic bombs, hoping to defeat a Germany that was potentially a year or more ahead in the deadly race. Fermi, working now at the University of Chicago, undertook the building of a full-scale reactor to demonstrate that a chain reaction could be achieved and controlled. By then it was known as well that a nuclear reactor would breed a newly discovered element, plutonium, an alternative nuclear explosive. Fermi’s reactor would also demonstrate the breeding of plutonium.

Instead of water, which absorbed too many neutrons, the demonstration reactor would use graphite, the form of carbon found in pencil lead, to slow the neutrons. Graphite blocks the size of planter boxes, drilled with blind holes to house slugs of uranium metal, would be stacked layer by layer to form a spherical matrix. Fermi, who loved American idioms, called his creation a “pile.”

Across the month of November 1942, Fermi supervised the building of Chicago Pile No. 1 on a doubles squash court under the west stands of the university football stadium. It was ready on the frigid morning of Dec. 2, 1942. Through the morning and early afternoon, wielding his slide rule, Fermi slowly took the pile critical, with a characteristically Fermian break for lunch. It worked, which meant a bomb would almost certainly work as well.

Historically, no other development in Fermi’s life ranks as high as the nuclear reactor, mighty versions of which produce more than 11 percent of the world’s electricity today. Fermi continued to contribute original scientific work throughout the war and postwar at the University of Chicago. He advised the United States government on atomic energy and worked on weapons problems during summer stints at Los Alamos. He opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb more vehemently than J. Robert Oppenheimer but escaped the ruination visited upon Oppenheimer by the vindictive chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis L. Strauss. He went on to help build the first hydrogen bomb.

I kept wishing this biography were livelier, lit with more surprises, but Schwartz, working with limited sources, tells the story well. A few infelicities are distracting. “Disinterested” doesn’t mean “uninterested.” “Fulsome” still means “offensively flattering,” not “generous,” though the meaning is changing. Brig. Gen. Leslie R. Groves of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, not Oppenheimer, held “authority over the entire Manhattan Project.” Oppenheimer was the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, one part of the project, where the first bombs were designed and built.

Still, these are minor mistakes. All in all, Schwartz’s biography adds importantly to the literature of the utterly remarkable men and women who opened up nuclear physics to the world.

An earlier version of this review misstated the year for which a German peace activist, Carl von Ossietzky, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. It was 1935, not 1936.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at [email protected] . Learn more

Richard Rhodes’s next book, “Energy: A Human History,” will be published in May.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

Cher Turns Back Time: In the first volume of her memoir (which she hasn’t read), the singer and actress explores a difficult childhood, fraught marriage to Sonny Bono and how she found her voice.

Reinventing the Romance Comic: To fully understand Charles Burns’s remarkable graphic novel, “Final Cut,” you have to look closely at the way in which it was rendered .

Turning to ‘Healing Fiction’: Cozy, whimsical novels — often featuring magical cats — that have long been popular in Japan and Korea are taking off globally. Fans say they offer comfort during a chaotic time .

The Book Review Podcast: Each week, top authors and critics talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Your subscription makes our work possible.

We want to bridge divides to reach everyone.

Deepen your worldview with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads .

'The Last Man Who Knew Everything' is a detailed and sympathetic biography of Enrico Fermi

'The Last Man Who Knew Everything' manages the neat double trick of making both Fermi and his abstruse work accessible

- By Steve Donoghue

Dec. 20, 2017, 9:00 a.m. ET

The title of David Schwartz's new biography of the great physicist Enrico Fermi, The Last Man Who Knew Everything , requires instantaneous clarification, and Schwartz provides it: about physics.

Fermi, one of the seminal 20th-century thinkers on atomics and quantum theory, was renowned even among his fellow hyper-specialists for being a hyper-specialist, a man who not only knew everything about physics – Schwartz's book isn't the first one to make clear that Fermi's colleagues were a little bit in awe of him – but seemed to care comparatively little about anything that wasn't physics.

“All physics, all the time,” one co-worker quipped, and although Schwartz's account is one of the most detailed and sympathetic lives of Fermi to appear in recent memory (2016's "The Pope of Physics," by Gino Segrè and Bettina Hoerlin is also excellent on the subject), it does little to change that view.

From his earliest years, when the prodigious nature of his scientific genius was noticed and encouraged by his teachers, Fermi concentrated with nearly overwhelming intensity on his chosen field, on pushing the boundaries and broadening the professional conceptions of physics. He was born in Rome in 1901, and in 1918 he began a course of intensive study at the Scuola Normale Superiore University in Pisa, taking a degree in 1922.

He soon became professor of theoretical physics at the Sapienza University of Rome and married Laura Capon, whose status as a Jew in Mussolini's increasingly anti-Semitic Italy made life tense for the couple. When Fermi won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1938, he and his family used the occasion to make their move to the United States, where Fermi took up his work at Columbia University.

Fermi's work in Rome on discovering the rudimentary properties of nuclear fission had been groundbreaking – it had won him the Nobel – but his work in America would be world-changing. In December of 1942, in a converted squash court just outside of Chicago proper, Fermi and his colleagues brought about the world's first controlled nuclear chain reaction.

As Schwartz puts it, “It was the first time humans tricked nature into releasing, in a sustained, controlled way, the energy embedded in the nucleus of the atom.” Fermi's team celebrated with a bottle of Chianti, but the mood was hardly cheerful. “Everyone understood,” Schwartz writes, “that this was a major step toward the development of a fission weapon.”

That was the explicit goal of the next and most famous stage of Fermi's life: as a lead scientist for the Manhattan Project, working on creating an atomic bomb. This will always present sympathetic Fermi biographers with a major hurdle. Schwartz maintains that the Manhattan Project scientists tend to come in for more condemnation than they deserve. “If history is to judge Fermi and his colleagues for their wartime work,” he writes, “it should be with a more nuanced perspective that appreciates the situation they faced and their motivations for participating.”

In Fermi's case, as in Szilard's or Oppenheimer's, this kind of double-talk is entirely unconvincing; the men and women working on the Manhattan project knew that they were developing the most horrifying weapon of mass destruction ever created, and they knew that if they refused, they were irreplaceable. They didn't refuse, and hundreds of thousands of civilians at Hiroshima and Nagasaki died as a result. No amount of nuanced thinking can absolve Fermi of complicity in those deaths, any more than Harry Truman can be absolved.

Fortunately, Schwartz doesn't hang his estimation of Fermi on any such kind of exoneration. Rather, he gives readers a rounded picture of the man. Fermi comes across in these pages as a mercurial figure, toweringly brilliant in his field and often curiously magnetic with friends and colleagues. Schwartz's description of Fermi's effectiveness as a team leader is convincing, and his personal assessment of Fermi, if occasionally less convincing, is always striving for balance: “He could be blunt, even dismissive if he believed someone was wrong, and his fondness for teasing those closest to him could be irritating, but he was never deliberately cruel.”

Fermi died in late 1954, having made a long series of fundamental breakthroughs in two or three different branches of physics (and, incidentally, having lent his name to the Fermi Paradox, which looks at the vastness of the visible universe and asks “Where are all the aliens?”) and ushered in the nuclear era.

"The Last Man Who Knew Everything" manages the neat double trick of making both Fermi and his abstruse work accessible to readers living in the world he did so much to create, for good and ill.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Unlimited digital access $11/month.

Digital subscription includes:

- Unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

- CSMonitor.com archive.

- The Monitor Daily email.

- No advertising.

- Cancel anytime.

Related stories

Test your knowledge are you a biography buff take our quiz, review 'troublemakers' follows the meteoric transformation of silicon valley’s founding generation, review 'woolly' is a page-turning look at scientists pushing the limits of dna research, share this article.

Link copied.

Dear Reader,

About a year ago, I happened upon this statement about the Monitor in the Harvard Business Review – under the charming heading of “do things that don’t interest you”:

“Many things that end up” being meaningful, writes social scientist Joseph Grenny, “have come from conference workshops, articles, or online videos that began as a chore and ended with an insight. My work in Kenya, for example, was heavily influenced by a Christian Science Monitor article I had forced myself to read 10 years earlier. Sometimes, we call things ‘boring’ simply because they lie outside the box we are currently in.”

If you were to come up with a punchline to a joke about the Monitor, that would probably be it. We’re seen as being global, fair, insightful, and perhaps a bit too earnest. We’re the bran muffin of journalism.

But you know what? We change lives. And I’m going to argue that we change lives precisely because we force open that too-small box that most human beings think they live in.

The Monitor is a peculiar little publication that’s hard for the world to figure out. We’re run by a church, but we’re not only for church members and we’re not about converting people. We’re known as being fair even as the world becomes as polarized as at any time since the newspaper’s founding in 1908.

We have a mission beyond circulation, we want to bridge divides. We’re about kicking down the door of thought everywhere and saying, “You are bigger and more capable than you realize. And we can prove it.”

If you’re looking for bran muffin journalism, you can subscribe to the Monitor for $15. You’ll get the Monitor Weekly magazine, the Monitor Daily email, and unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

Subscribe to insightful journalism

Subscription expired

Your subscription to The Christian Science Monitor has expired. You can renew your subscription or continue to use the site without a subscription.

Return to the free version of the site

If you have questions about your account, please contact customer service or call us at 1-617-450-2300 .

This message will appear once per week unless you renew or log out.

Session expired

Your session to The Christian Science Monitor has expired. We logged you out.

No subscription

You don’t have a Christian Science Monitor subscription yet.

Recently Visited

Top Categories

Children's Books

Discover Diverse Voices

More Categories

All Categories

New & Trending

Deals & Rewards

Best Sellers

From Our Editors

Memberships

Communities

- Biographies & Memoirs

Amazon Prime Free Trial

FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button and confirm your Prime free trial.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited FREE Prime delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -28% $25.07 $ 25 . 07 FREE delivery Sunday, December 8 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

We offer easy, convenient returns with at least one free return option: no shipping charges. All returns must comply with our returns policy.

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select your preferred free shipping option

- Drop off and leave!

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $16.31 $ 16 . 31 FREE delivery Sunday, December 8 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: JSBBookStore

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age Hardcover – Illustrated, December 5, 2017

Purchase options and add-ons

- Print length 480 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Basic Books

- Publication date December 5, 2017

- Dimensions 6.38 x 1.5 x 9.5 inches

- ISBN-10 0465072925

- ISBN-13 978-0465072927

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Basic Books; Illustrated edition (December 5, 2017)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 480 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0465072925

- ISBN-13 : 978-0465072927

- Item Weight : 1.55 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.38 x 1.5 x 9.5 inches

- #42 in Historical Italy Biographies

- #623 in Scientist Biographies

- #947 in History & Philosophy of Science (Books)

About the author

David n. schwartz.

David and Susan Schwartz are the co-authors of "The Joy of Costco: A Treasure Hunt from A to Z" (Hot Dog Press LLC, September 2023.) David is the author of several books, most recently "The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age" (Basic Books, 2017). He holds a BA from Stanford and a PhD from MIT. He has had a varied career, as a foreign policy specialist, an investment banker, an HR consultant, and an executive search professional. David Spent Much of his youth in San Francisco, where his parents were early members of Price Blub, Costco's predecessor. Susan Schwartz received a BA from the University of Pennsylvania and an MBA from Columbia University and has worked in marketing at Nabisco and General Foods. After leaving corporate America, she worked freelance making TV commercials for thirteen years before joining her husband David in executive search consulting. She worked as a professional baker for two years after college. She grew up in Philly where she delighted in shopping at Costco with her beloved parents.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 68% 22% 6% 2% 1% 68%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 68% 22% 6% 2% 1% 22%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 68% 22% 6% 2% 1% 6%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 68% 22% 6% 2% 1% 2%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 68% 22% 6% 2% 1% 1%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Customers say

Customers find the biography well-researched, interesting, and excellent. They describe the narrative as readable, engaging, and inspirational. Readers also mention the content is educational about physics and puts the fun back into science.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers find the biography well-researched, fascinating, and eye-opening. They say it's an excellent history and humanity lesson. Readers also mention the author keeps them engaged throughout with thorough fair-mindedness.

"...of what happened in those years is particularly accurate and evocative ...." Read more

"This is an extensive and detailed biography tracing Fermi's life, his associations with other scientists and why Fermi was considered one of the..." Read more

"This well-researched bio offers a wealth of interesting revelations (at least, to me) about one of the 20th century’s most important, relatively..." Read more

" Generally a good biography , especially regarding Fermi's period in Italy and through to Fermi's first demonstration of of a nuclear chain reaction..." Read more

Customers find the narrative readable, well-written, and excellent. They appreciate the rich storytelling and incredible grasp of events. Readers also mention that the story has extraordinary turns and is gripping.

"...The story has some extraordinary turns … Fermi traveling with his wife from Fascist Italy to Norway in December 1938 to receive the Nobel prize in..." Read more

"...The result is a very gratifying, readable narrative that, quite literally, I couldn't put down." Read more

"Good book and easy to read ." Read more

"...It reads like a thriller as we see him trying to start a controlled chain reaction without blowing himself up...." Read more

Customers find the book fun, gratifying, and inspirational. They say it's engaging and illuminating.

"... I enjoyed the read ." Read more

"...The result is a very gratifying , readable narrative that, quite literally, I couldn't put down." Read more

"...praises the physics community bestowed upon him, was revealing and inspirational , especially his zeal for teaching...." Read more

"...way of making both the science and the man accessible and enjoyable for the lay person ...." Read more

Customers find the physics content very educational, fascinating, and interesting. They say it puts the fun back into physics and has excellent subject matter.

"...happened during Fermi’s lifetime, and the clear explanation of related atomic physics phenomena ...." Read more

"A fascinating story of great science and a great scientist who truly lives up to the title -- and was able to put together the theoretical elements..." Read more

"I did not know about Enrico Fermi before this book. Very educational about physics that led to the building the atomic bomb." Read more

"A well written biography, extremely interesting . I knew a little about Fermi but had no idea how brilliant he was...." Read more

Reviews with images

Excellent book per se but it arrived in bad conditions

- Sort by reviews type Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Registry & Gift List

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Previous Article

- Next Article

The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Cameron Reed; The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age. Am. J. Phys. 1 April 2018; 86 (4): 319–320. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.5022689

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Enrico Fermi was one of the most accomplished and influential physicists of the twentieth century, but has been the subject of only a handful of biographical treatments. The first of these, Atoms in the Family , was written by his wife Laura shortly before his death in 1954. In 1970 came Emilio Segrè's Enrico Fermi, Physicist. Now after a gap of over a quarter-century, two new biographies of Fermi have recently appeared: Gino Segrè and Bettina Hoerlin's The Pope of Physics (2016), and David Schwartz's longer and somewhat more comprehensive The Last Man Who Knew Everything , the subject of this review. Gino Segrè is the nephew of Emilio Segrè and is himself a physicist. Schwartz is more removed from Fermi—he holds a Ph.D. in Political Science—and so brings a different perspective to his work, but is familiar with the physics world: His father, Melvin Schwartz, shared the 1988 Nobel Prize for Physics with Leon Lederman and Jack Steinberger for their discovery of the muon neutrino; Steinberger was a student of Fermi.

Schwartz relates that he became interested in Fermi when his mother came across a stash of letters and papers concerning Fermi left by his father, who died in 2006. Surprised that no full-length biography of Fermi was available, he set to the task. From the outset, Schwartz emphasizes the need to grasp how Fermi's remarkable breadth of knowledge and creativity were shaped by history, his personality, and the scientific and political circumstances of his times. He has succeeded admirably; the result is a very readable volume that should be in the collection of anyone interested in twentieth-century physics.

Schwartz breaks Fermi's life into four parts, proceeding largely chronologically: Becoming Fermi (from his birth in 1901 through his education and early academic appointments until late 1925), The Rome Years (1926–1938), The Manhattan Project (1939–1945), and The Chicago Years (1946–1954). These parts comprise 27 fast-paced and very readable chapters; there are also extensive notes and a bibliography. Schwartz has made good use of Fermi's collected papers, primary and secondary literature, and interviews with Fermi family members and many of Fermi's colleagues and students, and members of their families. Fermi was held in high regard as a teacher and mentor, and the recollections of his students are particularly illuminating and poignant.

Fermi's most notable contributions to physics are of course his development of Fermi-Dirac statistics, his theory of beta-decay and the weak interaction, the discovery with his Rome collaborators of neutron-induced radioactivity (which eventually led to the production of transuranic elements), the quasi-accidental discovery of the effect of thermalizing neutrons on reaction cross-sections, and the construction of the first chain-reacting nuclear pile at the University of Chicago. An unidentified Chicago colleague of Fermi's reportedly said that he learned how to “think like a neutron.” No matter how many times one reads of the slow-neutron discovery, one is struck by the dramatic confluence of conflicting evidence, luck, and chance favoring a mind armed with deep background knowledge. Fermi and his Rome group came infinitesimally close to discovering fission in 1934, and one can only wonder how different subsequent history might have been had they done so. The story of the startup of the CP-1 pile at Chicago on December 2, 1942 is no less dramatic, but the drama had a different flavor. Based on experiments with 29 prior subcritical piles at both Columbia and Chicago, Fermi knew full well what to expect, but played to his audience's appreciation of being present at a historic event by drawing out the approach to criticality in incremental steps. CP-1 ran at a power output of one-half of a Watt that day. Only two years later, the gargantuan 250-megawatt plutonium production reactors at Hanford, descendants of CP-1, were beginning to come online, a remarkable testimony to the scientific, engineering, and organizational talent deployed in the Manhattan Project.

In the spring and summer of 1945, Fermi served on a panel with Robert Oppenheimer, Arthur Compton, and Ernest Lawrence which advised the Interim Committee, which had been established by Secretary of War Henry Stimson to provide advice on atomic policies. Fermi was present during a critical meeting at which it was concluded that Japan should not be given advance warning as to impending use of the bombs. Schwartz infers, however, that Fermi was uncomfortable with this decision, but went along perhaps because he was sensitive to his position as a foreign-born national of what had until recently been an enemy country. As Schwartz accurately points out, Manhattan Project scientists have assumed a greater burden of guilt than they deserve for the bombings: By that point the decision was in the hands of generals and politicians. A few years later Fermi found himself in a similar situation when, as a member of the General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), he strongly opposed development of the much more destructive hydrogen bomb. Despite this, he dutifully returned to Los Alamos to work on it following President Truman's early-1950 directive that research on such weapons be accelerated.

I caught a few surprising errors in this book. Einstein did not coin or even ever use the term “photon” (p. 44; this is usually attributed American chemist Gilbert Lewis in 1926, although he did not have the modern sense in mind and there were earlier precedents); it is claimed that the DuPont company had no previous involvement with the United States military (p. 207; DuPont was extensively involved in the production of propellants); and Oppenheimer did not view the Trinity test from Campaña Hill (p. 257; he was at the South-10,000 control station). Astrophysicist Hannes Alfvèn's name is misspelt and he is transformed from a Swede into a Norwegian on p. 282. Some people appear with little or no explanation of their background or relationship to the story; this occurs with Vannevar Bush (p. 185) and James Conant (p. 212), two senior administrators of the Manhattan Project, and also with Ward Evans (p. 313), who was one of the panelists on Oppenheimer's 1954 security hearing. These are, however, fairly minor issues that are not likely to be caught by readers who are not intimately familiar with the relevant history and physics, and they certainly do not detract from appreciation of Fermi's life and work. Schwartz has a habit of playing amateur psychologist, such as when he attributes Fermi's lifelong interest in analyzing probabilities to the unexpected and very upsetting death of his older brother Giulio when Fermi was 13. In what struck me as an extremely unfair assessment, Schwartz strongly criticizes Fermi for not anticipating the effects of neutron-capturing xenon-135 during the startup of the first Hanford reactor. Xe-135 is formed from the decay of iodine-135, which is a direct fission product. However, fission leads to literally hundreds of products which themselves decay to other species, and the detailed behavior of any one product simply could not have been predicted in advance. Indeed, DuPont engineers over-designed the piles as a precaution against exactly this type of contingency.

In the end, much will remain unknown about Fermi's thoughts on the use and legacy of nuclear energy and weapons: He left little in the way of private letters, diaries, or memoirs, and never achieved the level of public exposure and political influence that contemporaries such as Oppenheimer or Edward Teller sought. But the value of his contributions to physics and quality of his character will remain unquestioned, and long-overdue biographies such as this will help bring appreciation of his contributions to a wider audience.

Cameron Reed is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Physics at Alma College, emeritus. He served as the editor of the American Physical Society's “Physics & Society” newsletter from 2009–2013, and is currently Secretary-Treasurer of the APS's Forum on the History of Physics. His interests lie in the physics and history of nuclear weapons; his text “The History and Science of the Manhattan Project” was published by Springer in late 2013.

Citing articles via

Submit your article.

Sign up for alerts

Related Content

- Online ISSN 1943-2909

- Print ISSN 0002-9505

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age

Embed our reviews widget for this book

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

December 2, 2024

- Ed Simon on the belief in Greek gods

- Hua Hsu remembers Giant Robot

- The impact of war on Burmese poetry

IMAGES

VIDEO