- The 25 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History

While each year thousands and thousands of studies are completed in the many specialty areas of psychology, there are a handful that, over the years, have had a lasting impact in the psychological community as a whole. Some of these were dutifully conducted, keeping within the confines of ethical and practical guidelines. Others pushed the boundaries of human behavior during their psychological experiments and created controversies that still linger to this day. And still others were not designed to be true psychological experiments, but ended up as beacons to the psychological community in proving or disproving theories.

This is a list of the 25 most influential psychological experiments still being taught to psychology students of today.

1. A Class Divided

Study conducted by: jane elliott.

Study Conducted in 1968 in an Iowa classroom

Experiment Details: Jane Elliott’s famous experiment was inspired by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the inspirational life that he led. The third grade teacher developed an exercise, or better yet, a psychological experiment, to help her Caucasian students understand the effects of racism and prejudice.

Elliott divided her class into two separate groups: blue-eyed students and brown-eyed students. On the first day, she labeled the blue-eyed group as the superior group and from that point forward they had extra privileges, leaving the brown-eyed children to represent the minority group. She discouraged the groups from interacting and singled out individual students to stress the negative characteristics of the children in the minority group. What this exercise showed was that the children’s behavior changed almost instantaneously. The group of blue-eyed students performed better academically and even began bullying their brown-eyed classmates. The brown-eyed group experienced lower self-confidence and worse academic performance. The next day, she reversed the roles of the two groups and the blue-eyed students became the minority group.

At the end of the experiment, the children were so relieved that they were reported to have embraced one another and agreed that people should not be judged based on outward appearances. This exercise has since been repeated many times with similar outcomes.

For more information click here

2. Asch Conformity Study

Study conducted by: dr. solomon asch.

Study Conducted in 1951 at Swarthmore College

Experiment Details: Dr. Solomon Asch conducted a groundbreaking study that was designed to evaluate a person’s likelihood to conform to a standard when there is pressure to do so.

A group of participants were shown pictures with lines of various lengths and were then asked a simple question: Which line is longest? The tricky part of this study was that in each group only one person was a true participant. The others were actors with a script. Most of the actors were instructed to give the wrong answer. Strangely, the one true participant almost always agreed with the majority, even though they knew they were giving the wrong answer.

The results of this study are important when we study social interactions among individuals in groups. This study is a famous example of the temptation many of us experience to conform to a standard during group situations and it showed that people often care more about being the same as others than they do about being right. It is still recognized as one of the most influential psychological experiments for understanding human behavior.

3. Bobo Doll Experiment

Study conducted by: dr. alburt bandura.

Study Conducted between 1961-1963 at Stanford University

In his groundbreaking study he separated participants into three groups:

- one was exposed to a video of an adult showing aggressive behavior towards a Bobo doll

- another was exposed to video of a passive adult playing with the Bobo doll

- the third formed a control group

Children watched their assigned video and then were sent to a room with the same doll they had seen in the video (with the exception of those in the control group). What the researcher found was that children exposed to the aggressive model were more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior towards the doll themselves. The other groups showed little imitative aggressive behavior. For those children exposed to the aggressive model, the number of derivative physical aggressions shown by the boys was 38.2 and 12.7 for the girls.

The study also showed that boys exhibited more aggression when exposed to aggressive male models than boys exposed to aggressive female models. When exposed to aggressive male models, the number of aggressive instances exhibited by boys averaged 104. This is compared to 48.4 aggressive instances exhibited by boys who were exposed to aggressive female models.

While the results for the girls show similar findings, the results were less drastic. When exposed to aggressive female models, the number of aggressive instances exhibited by girls averaged 57.7. This is compared to 36.3 aggressive instances exhibited by girls who were exposed to aggressive male models. The results concerning gender differences strongly supported Bandura’s secondary prediction that children will be more strongly influenced by same-sex models. The Bobo Doll Experiment showed a groundbreaking way to study human behavior and it’s influences.

4. Car Crash Experiment

Study conducted by: elizabeth loftus and john palmer.

Study Conducted in 1974 at The University of California in Irvine

The participants watched slides of a car accident and were asked to describe what had happened as if they were eyewitnesses to the scene. The participants were put into two groups and each group was questioned using different wording such as “how fast was the car driving at the time of impact?” versus “how fast was the car going when it smashed into the other car?” The experimenters found that the use of different verbs affected the participants’ memories of the accident, showing that memory can be easily distorted.

This research suggests that memory can be easily manipulated by questioning technique. This means that information gathered after the event can merge with original memory causing incorrect recall or reconstructive memory. The addition of false details to a memory of an event is now referred to as confabulation. This concept has very important implications for the questions used in police interviews of eyewitnesses.

5. Cognitive Dissonance Experiment

Study conducted by: leon festinger and james carlsmith.

Study Conducted in 1957 at Stanford University

Experiment Details: The concept of cognitive dissonance refers to a situation involving conflicting:

This conflict produces an inherent feeling of discomfort leading to a change in one of the attitudes, beliefs or behaviors to minimize or eliminate the discomfort and restore balance.

Cognitive dissonance was first investigated by Leon Festinger, after an observational study of a cult that believed that the earth was going to be destroyed by a flood. Out of this study was born an intriguing experiment conducted by Festinger and Carlsmith where participants were asked to perform a series of dull tasks (such as turning pegs in a peg board for an hour). Participant’s initial attitudes toward this task were highly negative.

They were then paid either $1 or $20 to tell a participant waiting in the lobby that the tasks were really interesting. Almost all of the participants agreed to walk into the waiting room and persuade the next participant that the boring experiment would be fun. When the participants were later asked to evaluate the experiment, the participants who were paid only $1 rated the tedious task as more fun and enjoyable than the participants who were paid $20 to lie.

Being paid only $1 is not sufficient incentive for lying and so those who were paid $1 experienced dissonance. They could only overcome that cognitive dissonance by coming to believe that the tasks really were interesting and enjoyable. Being paid $20 provides a reason for turning pegs and there is therefore no dissonance.

6. Fantz’s Looking Chamber

Study conducted by: robert l. fantz.

Study Conducted in 1961 at the University of Illinois

Experiment Details: The study conducted by Robert L. Fantz is among the simplest, yet most important in the field of infant development and vision. In 1961, when this experiment was conducted, there very few ways to study what was going on in the mind of an infant. Fantz realized that the best way was to simply watch the actions and reactions of infants. He understood the fundamental factor that if there is something of interest near humans, they generally look at it.

To test this concept, Fantz set up a display board with two pictures attached. On one was a bulls-eye. On the other was the sketch of a human face. This board was hung in a chamber where a baby could lie safely underneath and see both images. Then, from behind the board, invisible to the baby, he peeked through a hole to watch what the baby looked at. This study showed that a two-month old baby looked twice as much at the human face as it did at the bulls-eye. This suggests that human babies have some powers of pattern and form selection. Before this experiment it was thought that babies looked out onto a chaotic world of which they could make little sense.

7. Hawthorne Effect

Study conducted by: henry a. landsberger.

Study Conducted in 1955 at Hawthorne Works in Chicago, Illinois

Landsberger performed the study by analyzing data from experiments conducted between 1924 and 1932, by Elton Mayo, at the Hawthorne Works near Chicago. The company had commissioned studies to evaluate whether the level of light in a building changed the productivity of the workers. What Mayo found was that the level of light made no difference in productivity. The workers increased their output whenever the amount of light was switched from a low level to a high level, or vice versa.

The researchers noticed a tendency that the workers’ level of efficiency increased when any variable was manipulated. The study showed that the output changed simply because the workers were aware that they were under observation. The conclusion was that the workers felt important because they were pleased to be singled out. They increased productivity as a result. Being singled out was the factor dictating increased productivity, not the changing lighting levels, or any of the other factors that they experimented upon.

The Hawthorne Effect has become one of the hardest inbuilt biases to eliminate or factor into the design of any experiment in psychology and beyond.

8. Kitty Genovese Case

Study conducted by: new york police force.

Study Conducted in 1964 in New York City

Experiment Details: The murder case of Kitty Genovese was never intended to be a psychological experiment, however it ended up having serious implications for the field.

According to a New York Times article, almost 40 neighbors witnessed Kitty Genovese being savagely attacked and murdered in Queens, New York in 1964. Not one neighbor called the police for help. Some reports state that the attacker briefly left the scene and later returned to “finish off” his victim. It was later uncovered that many of these facts were exaggerated. (There were more likely only a dozen witnesses and records show that some calls to police were made).

What this case later become famous for is the “Bystander Effect,” which states that the more bystanders that are present in a social situation, the less likely it is that anyone will step in and help. This effect has led to changes in medicine, psychology and many other areas. One famous example is the way CPR is taught to new learners. All students in CPR courses learn that they must assign one bystander the job of alerting authorities which minimizes the chances of no one calling for assistance.

9. Learned Helplessness Experiment

Study conducted by: martin seligman.

Study Conducted in 1967 at the University of Pennsylvania

Seligman’s experiment involved the ringing of a bell and then the administration of a light shock to a dog. After a number of pairings, the dog reacted to the shock even before it happened. As soon as the dog heard the bell, he reacted as though he’d already been shocked.

During the course of this study something unexpected happened. Each dog was placed in a large crate that was divided down the middle with a low fence. The dog could see and jump over the fence easily. The floor on one side of the fence was electrified, but not on the other side of the fence. Seligman placed each dog on the electrified side and administered a light shock. He expected the dog to jump to the non-shocking side of the fence. In an unexpected turn, the dogs simply laid down.

The hypothesis was that as the dogs learned from the first part of the experiment that there was nothing they could do to avoid the shocks, they gave up in the second part of the experiment. To prove this hypothesis the experimenters brought in a new set of animals and found that dogs with no history in the experiment would jump over the fence.

This condition was described as learned helplessness. A human or animal does not attempt to get out of a negative situation because the past has taught them that they are helpless.

10. Little Albert Experiment

Study conducted by: john b. watson and rosalie rayner.

Study Conducted in 1920 at Johns Hopkins University

The experiment began by placing a white rat in front of the infant, who initially had no fear of the animal. Watson then produced a loud sound by striking a steel bar with a hammer every time little Albert was presented with the rat. After several pairings (the noise and the presentation of the white rat), the boy began to cry and exhibit signs of fear every time the rat appeared in the room. Watson also created similar conditioned reflexes with other common animals and objects (rabbits, Santa beard, etc.) until Albert feared them all.

This study proved that classical conditioning works on humans. One of its most important implications is that adult fears are often connected to early childhood experiences.

11. Magical Number Seven

Study conducted by: george a. miller.

Study Conducted in 1956 at Princeton University

Experiment Details: Frequently referred to as “ Miller’s Law,” the Magical Number Seven experiment purports that the number of objects an average human can hold in working memory is 7 ± 2. This means that the human memory capacity typically includes strings of words or concepts ranging from 5-9. This information on the limits to the capacity for processing information became one of the most highly cited papers in psychology.

The Magical Number Seven Experiment was published in 1956 by cognitive psychologist George A. Miller of Princeton University’s Department of Psychology in Psychological Review . In the article, Miller discussed a concurrence between the limits of one-dimensional absolute judgment and the limits of short-term memory.

In a one-dimensional absolute-judgment task, a person is presented with a number of stimuli that vary on one dimension (such as 10 different tones varying only in pitch). The person responds to each stimulus with a corresponding response (learned before).

Performance is almost perfect up to five or six different stimuli but declines as the number of different stimuli is increased. This means that a human’s maximum performance on one-dimensional absolute judgment can be described as an information store with the maximum capacity of approximately 2 to 3 bits of information There is the ability to distinguish between four and eight alternatives.

12. Pavlov’s Dog Experiment

Study conducted by: ivan pavlov.

Study Conducted in the 1890s at the Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg, Russia

Pavlov began with the simple idea that there are some things that a dog does not need to learn. He observed that dogs do not learn to salivate when they see food. This reflex is “hard wired” into the dog. This is an unconditioned response (a stimulus-response connection that required no learning).

Pavlov outlined that there are unconditioned responses in the animal by presenting a dog with a bowl of food and then measuring its salivary secretions. In the experiment, Pavlov used a bell as his neutral stimulus. Whenever he gave food to his dogs, he also rang a bell. After a number of repeats of this procedure, he tried the bell on its own. What he found was that the bell on its own now caused an increase in salivation. The dog had learned to associate the bell and the food. This learning created a new behavior. The dog salivated when he heard the bell. Because this response was learned (or conditioned), it is called a conditioned response. The neutral stimulus has become a conditioned stimulus.

This theory came to be known as classical conditioning.

13. Robbers Cave Experiment

Study conducted by: muzafer and carolyn sherif.

Study Conducted in 1954 at the University of Oklahoma

Experiment Details: This experiment, which studied group conflict, is considered by most to be outside the lines of what is considered ethically sound.

In 1954 researchers at the University of Oklahoma assigned 22 eleven- and twelve-year-old boys from similar backgrounds into two groups. The two groups were taken to separate areas of a summer camp facility where they were able to bond as social units. The groups were housed in separate cabins and neither group knew of the other’s existence for an entire week. The boys bonded with their cabin mates during that time. Once the two groups were allowed to have contact, they showed definite signs of prejudice and hostility toward each other even though they had only been given a very short time to develop their social group. To increase the conflict between the groups, the experimenters had them compete against each other in a series of activities. This created even more hostility and eventually the groups refused to eat in the same room. The final phase of the experiment involved turning the rival groups into friends. The fun activities the experimenters had planned like shooting firecrackers and watching movies did not initially work, so they created teamwork exercises where the two groups were forced to collaborate. At the end of the experiment, the boys decided to ride the same bus home, demonstrating that conflict can be resolved and prejudice overcome through cooperation.

Many critics have compared this study to Golding’s Lord of the Flies novel as a classic example of prejudice and conflict resolution.

14. Ross’ False Consensus Effect Study

Study conducted by: lee ross.

Study Conducted in 1977 at Stanford University

Experiment Details: In 1977, a social psychology professor at Stanford University named Lee Ross conducted an experiment that, in lay terms, focuses on how people can incorrectly conclude that others think the same way they do, or form a “false consensus” about the beliefs and preferences of others. Ross conducted the study in order to outline how the “false consensus effect” functions in humans.

Featured Programs

In the first part of the study, participants were asked to read about situations in which a conflict occurred and then were told two alternative ways of responding to the situation. They were asked to do three things:

- Guess which option other people would choose

- Say which option they themselves would choose

- Describe the attributes of the person who would likely choose each of the two options

What the study showed was that most of the subjects believed that other people would do the same as them, regardless of which of the two responses they actually chose themselves. This phenomenon is referred to as the false consensus effect, where an individual thinks that other people think the same way they do when they may not. The second observation coming from this important study is that when participants were asked to describe the attributes of the people who will likely make the choice opposite of their own, they made bold and sometimes negative predictions about the personalities of those who did not share their choice.

15. The Schachter and Singer Experiment on Emotion

Study conducted by: stanley schachter and jerome e. singer.

Study Conducted in 1962 at Columbia University

Experiment Details: In 1962 Schachter and Singer conducted a ground breaking experiment to prove their theory of emotion.

In the study, a group of 184 male participants were injected with epinephrine, a hormone that induces arousal including increased heartbeat, trembling, and rapid breathing. The research participants were told that they were being injected with a new medication to test their eyesight. The first group of participants was informed the possible side effects that the injection might cause while the second group of participants were not. The participants were then placed in a room with someone they thought was another participant, but was actually a confederate in the experiment. The confederate acted in one of two ways: euphoric or angry. Participants who had not been informed about the effects of the injection were more likely to feel either happier or angrier than those who had been informed.

What Schachter and Singer were trying to understand was the ways in which cognition or thoughts influence human emotion. Their study illustrates the importance of how people interpret their physiological states, which form an important component of your emotions. Though their cognitive theory of emotional arousal dominated the field for two decades, it has been criticized for two main reasons: the size of the effect seen in the experiment was not that significant and other researchers had difficulties repeating the experiment.

16. Selective Attention / Invisible Gorilla Experiment

Study conducted by: daniel simons and christopher chabris.

Study Conducted in 1999 at Harvard University

Experiment Details: In 1999 Simons and Chabris conducted their famous awareness test at Harvard University.

Participants in the study were asked to watch a video and count how many passes occurred between basketball players on the white team. The video moves at a moderate pace and keeping track of the passes is a relatively easy task. What most people fail to notice amidst their counting is that in the middle of the test, a man in a gorilla suit walked onto the court and stood in the center before walking off-screen.

The study found that the majority of the subjects did not notice the gorilla at all, proving that humans often overestimate their ability to effectively multi-task. What the study set out to prove is that when people are asked to attend to one task, they focus so strongly on that element that they may miss other important details.

17. Stanford Prison Study

Study conducted by philip zimbardo.

Study Conducted in 1971 at Stanford University

The Stanford Prison Experiment was designed to study behavior of “normal” individuals when assigned a role of prisoner or guard. College students were recruited to participate. They were assigned roles of “guard” or “inmate.” Zimbardo played the role of the warden. The basement of the psychology building was the set of the prison. Great care was taken to make it look and feel as realistic as possible.

The prison guards were told to run a prison for two weeks. They were told not to physically harm any of the inmates during the study. After a few days, the prison guards became very abusive verbally towards the inmates. Many of the prisoners became submissive to those in authority roles. The Stanford Prison Experiment inevitably had to be cancelled because some of the participants displayed troubling signs of breaking down mentally.

Although the experiment was conducted very unethically, many psychologists believe that the findings showed how much human behavior is situational. People will conform to certain roles if the conditions are right. The Stanford Prison Experiment remains one of the most famous psychology experiments of all time.

18. Stanley Milgram Experiment

Study conducted by stanley milgram.

Study Conducted in 1961 at Stanford University

Experiment Details: This 1961 study was conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram. It was designed to measure people’s willingness to obey authority figures when instructed to perform acts that conflicted with their morals. The study was based on the premise that humans will inherently take direction from authority figures from very early in life.

Participants were told they were participating in a study on memory. They were asked to watch another person (an actor) do a memory test. They were instructed to press a button that gave an electric shock each time the person got a wrong answer. (The actor did not actually receive the shocks, but pretended they did).

Participants were told to play the role of “teacher” and administer electric shocks to “the learner,” every time they answered a question incorrectly. The experimenters asked the participants to keep increasing the shocks. Most of them obeyed even though the individual completing the memory test appeared to be in great pain. Despite these protests, many participants continued the experiment when the authority figure urged them to. They increased the voltage after each wrong answer until some eventually administered what would be lethal electric shocks.

This experiment showed that humans are conditioned to obey authority and will usually do so even if it goes against their natural morals or common sense.

19. Surrogate Mother Experiment

Study conducted by: harry harlow.

Study Conducted from 1957-1963 at the University of Wisconsin

Experiment Details: In a series of controversial experiments during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Harry Harlow studied the importance of a mother’s love for healthy childhood development.

In order to do this he separated infant rhesus monkeys from their mothers a few hours after birth and left them to be raised by two “surrogate mothers.” One of the surrogates was made of wire with an attached bottle for food. The other was made of soft terrycloth but lacked food. The researcher found that the baby monkeys spent much more time with the cloth mother than the wire mother, thereby proving that affection plays a greater role than sustenance when it comes to childhood development. They also found that the monkeys that spent more time cuddling the soft mother grew up to healthier.

This experiment showed that love, as demonstrated by physical body contact, is a more important aspect of the parent-child bond than the provision of basic needs. These findings also had implications in the attachment between fathers and their infants when the mother is the source of nourishment.

20. The Good Samaritan Experiment

Study conducted by: john darley and daniel batson.

Study Conducted in 1973 at The Princeton Theological Seminary (Researchers were from Princeton University)

Experiment Details: In 1973, an experiment was created by John Darley and Daniel Batson, to investigate the potential causes that underlie altruistic behavior. The researchers set out three hypotheses they wanted to test:

- People thinking about religion and higher principles would be no more inclined to show helping behavior than laymen.

- People in a rush would be much less likely to show helping behavior.

- People who are religious for personal gain would be less likely to help than people who are religious because they want to gain some spiritual and personal insights into the meaning of life.

Student participants were given some religious teaching and instruction. They were then were told to travel from one building to the next. Between the two buildings was a man lying injured and appearing to be in dire need of assistance. The first variable being tested was the degree of urgency impressed upon the subjects, with some being told not to rush and others being informed that speed was of the essence.

The results of the experiment were intriguing, with the haste of the subject proving to be the overriding factor. When the subject was in no hurry, nearly two-thirds of people stopped to lend assistance. When the subject was in a rush, this dropped to one in ten.

People who were on the way to deliver a speech about helping others were nearly twice as likely to help as those delivering other sermons,. This showed that the thoughts of the individual were a factor in determining helping behavior. Religious beliefs did not appear to make much difference on the results. Being religious for personal gain, or as part of a spiritual quest, did not appear to make much of an impact on the amount of helping behavior shown.

21. The Halo Effect Experiment

Study conducted by: richard e. nisbett and timothy decamp wilson.

Study Conducted in 1977 at the University of Michigan

Experiment Details: The Halo Effect states that people generally assume that people who are physically attractive are more likely to:

- be intelligent

- be friendly

- display good judgment

To prove their theory, Nisbett and DeCamp Wilson created a study to prove that people have little awareness of the nature of the Halo Effect. They’re not aware that it influences:

- their personal judgments

- the production of a more complex social behavior

In the experiment, college students were the research participants. They were asked to evaluate a psychology instructor as they view him in a videotaped interview. The students were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Each group was shown one of two different interviews with the same instructor. The instructor is a native French-speaking Belgian who spoke English with a noticeable accent. In the first video, the instructor presented himself as someone:

- respectful of his students’ intelligence and motives

- flexible in his approach to teaching

- enthusiastic about his subject matter

In the second interview, he presented himself as much more unlikable. He was cold and distrustful toward the students and was quite rigid in his teaching style.

After watching the videos, the subjects were asked to rate the lecturer on:

- physical appearance

His mannerisms and accent were kept the same in both versions of videos. The subjects were asked to rate the professor on an 8-point scale ranging from “like extremely” to “dislike extremely.” Subjects were also told that the researchers were interested in knowing “how much their liking for the teacher influenced the ratings they just made.” Other subjects were asked to identify how much the characteristics they just rated influenced their liking of the teacher.

After responding to the questionnaire, the respondents were puzzled about their reactions to the videotapes and to the questionnaire items. The students had no idea why they gave one lecturer higher ratings. Most said that how much they liked the lecturer had not affected their evaluation of his individual characteristics at all.

The interesting thing about this study is that people can understand the phenomenon, but they are unaware when it is occurring. Without realizing it, humans make judgments. Even when it is pointed out, they may still deny that it is a product of the halo effect phenomenon.

22. The Marshmallow Test

Study conducted by: walter mischel.

Study Conducted in 1972 at Stanford University

In his 1972 Marshmallow Experiment, children ages four to six were taken into a room where a marshmallow was placed in front of them on a table. Before leaving each of the children alone in the room, the experimenter informed them that they would receive a second marshmallow if the first one was still on the table after they returned in 15 minutes. The examiner recorded how long each child resisted eating the marshmallow and noted whether it correlated with the child’s success in adulthood. A small number of the 600 children ate the marshmallow immediately and one-third delayed gratification long enough to receive the second marshmallow.

In follow-up studies, Mischel found that those who deferred gratification were significantly more competent and received higher SAT scores than their peers. This characteristic likely remains with a person for life. While this study seems simplistic, the findings outline some of the foundational differences in individual traits that can predict success.

23. The Monster Study

Study conducted by: wendell johnson.

Study Conducted in 1939 at the University of Iowa

Experiment Details: The Monster Study received this negative title due to the unethical methods that were used to determine the effects of positive and negative speech therapy on children.

Wendell Johnson of the University of Iowa selected 22 orphaned children, some with stutters and some without. The children were in two groups. The group of children with stutters was placed in positive speech therapy, where they were praised for their fluency. The non-stutterers were placed in negative speech therapy, where they were disparaged for every mistake in grammar that they made.

As a result of the experiment, some of the children who received negative speech therapy suffered psychological effects and retained speech problems for the rest of their lives. They were examples of the significance of positive reinforcement in education.

The initial goal of the study was to investigate positive and negative speech therapy. However, the implication spanned much further into methods of teaching for young children.

24. Violinist at the Metro Experiment

Study conducted by: staff at the washington post.

Study Conducted in 2007 at a Washington D.C. Metro Train Station

During the study, pedestrians rushed by without realizing that the musician playing at the entrance to the metro stop was Grammy-winning musician, Joshua Bell. Two days before playing in the subway, he sold out at a theater in Boston where the seats average $100. He played one of the most intricate pieces ever written with a violin worth 3.5 million dollars. In the 45 minutes the musician played his violin, only 6 people stopped and stayed for a while. Around 20 gave him money, but continued to walk their normal pace. He collected $32.

The study and the subsequent article organized by the Washington Post was part of a social experiment looking at:

- the priorities of people

Gene Weingarten wrote about the social experiment: “In a banal setting at an inconvenient time, would beauty transcend?” Later he won a Pulitzer Prize for his story. Some of the questions the article addresses are:

- Do we perceive beauty?

- Do we stop to appreciate it?

- Do we recognize the talent in an unexpected context?

As it turns out, many of us are not nearly as perceptive to our environment as we might like to think.

25. Visual Cliff Experiment

Study conducted by: eleanor gibson and richard walk.

Study Conducted in 1959 at Cornell University

Experiment Details: In 1959, psychologists Eleanor Gibson and Richard Walk set out to study depth perception in infants. They wanted to know if depth perception is a learned behavior or if it is something that we are born with. To study this, Gibson and Walk conducted the visual cliff experiment.

They studied 36 infants between the ages of six and 14 months, all of whom could crawl. The infants were placed one at a time on a visual cliff. A visual cliff was created using a large glass table that was raised about a foot off the floor. Half of the glass table had a checker pattern underneath in order to create the appearance of a ‘shallow side.’

In order to create a ‘deep side,’ a checker pattern was created on the floor; this side is the visual cliff. The placement of the checker pattern on the floor creates the illusion of a sudden drop-off. Researchers placed a foot-wide centerboard between the shallow side and the deep side. Gibson and Walk found the following:

- Nine of the infants did not move off the centerboard.

- All of the 27 infants who did move crossed into the shallow side when their mothers called them from the shallow side.

- Three of the infants crawled off the visual cliff toward their mother when called from the deep side.

- When called from the deep side, the remaining 24 children either crawled to the shallow side or cried because they could not cross the visual cliff and make it to their mother.

What this study helped demonstrate is that depth perception is likely an inborn train in humans.

Among these experiments and psychological tests, we see boundaries pushed and theories taking on a life of their own. It is through the endless stream of psychological experimentation that we can see simple hypotheses become guiding theories for those in this field. The greater field of psychology became a formal field of experimental study in 1879, when Wilhelm Wundt established the first laboratory dedicated solely to psychological research in Leipzig, Germany. Wundt was the first person to refer to himself as a psychologist. Since 1879, psychology has grown into a massive collection of:

- methods of practice

It’s also a specialty area in the field of healthcare. None of this would have been possible without these and many other important psychological experiments that have stood the test of time.

- 20 Most Unethical Experiments in Psychology

- What Careers are in Experimental Psychology?

- 10 Things to Know About the Psychology of Psychotherapy

About Education: Psychology

Explorable.com

Mental Floss.com

About the Author

After earning a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Rutgers University and then a Master of Science in Clinical and Forensic Psychology from Drexel University, Kristen began a career as a therapist at two prisons in Philadelphia. At the same time she volunteered as a rape crisis counselor, also in Philadelphia. After a few years in the field she accepted a teaching position at a local college where she currently teaches online psychology courses. Kristen began writing in college and still enjoys her work as a writer, editor, professor and mother.

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. Marriage and Family Counseling Programs

- Top 5 Online Doctorate in Educational Psychology

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology Programs

- Top 10 Online Master’s in Forensic Psychology

- 10 Most Affordable Counseling Psychology Online Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Industrial Organizational Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Developmental Psychology Online Programs

- 15 Most Affordable Online Sport Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable School Psychology Online Degree Programs

- Top 50 Online Psychology Master’s Degree Programs

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Educational Psychology

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Industrial/Organizational Psychology

- Top 10 Most Affordable Online Master’s in Clinical Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 6 Most Affordable Online PhD/PsyD Programs in Clinical Psychology

- 50 Great Small Colleges for a Bachelor’s in Psychology

- 50 Most Innovative University Psychology Departments

- The 30 Most Influential Cognitive Psychologists Alive Today

- Top 30 Affordable Online Psychology Degree Programs

- 30 Most Influential Neuroscientists

- Top 40 Websites for Psychology Students and Professionals

- Top 30 Psychology Blogs

- 25 Celebrities With Animal Phobias

- Your Phobias Illustrated (Infographic)

- 15 Inspiring TED Talks on Overcoming Challenges

- 10 Fascinating Facts About the Psychology of Color

- 15 Scariest Mental Disorders of All Time

- 15 Things to Know About Mental Disorders in Animals

- 13 Most Deranged Serial Killers of All Time

Site Information

- About Online Psychology Degree Guide

- Virginia Beach

- History & facts

- Famous people

- Famous landmarks

- AI interviews

- Science & Nature

- Tech & Business

Discover something new everyday

- Famous places

- Food & Drinks

- Tech & Business

20 Famous Psychology Experiments That Shaped Our Understanding

Read Next →

Where to Swim in Lisbon

How to find English speaking movies in Paris

Top 15 Interesting Facts about The Renaissance

1.stanford prison experiment.

2.Milgram Experiment

3.little albert experiment.

4.Asch Conformity Experiment

5.harlow’s monkey experiment.

6.Bobo Doll Experiment

7.the marshmallow test.

8.Robbers Cave Experiment

9.the monster study.

10.The Standford Marshmallow Experiment

11.the hawthorne effect.

12.The Strange Situation

13.the still face experiment.

14.Pavlov’s Dogs

15.the milgram experiment.

16.The Robbers Cave Experiment

17.the harlow monkey experiment, 18.the bystander effect, 19.the zimbardo prison experiment.

20.The Ainsworth Strange Situation Experiment

Planning a trip to Paris ? Get ready !

These are Amazon’s best-selling travel products that you may need for coming to Paris.

- The best travel book : Rick Steves – Paris 2023 – Learn more here

- Fodor’s Paris 2024 – Learn more here

Travel Gear

- Venture Pal Lightweight Backpack – Learn more here

- Samsonite Winfield 2 28″ Luggage – Learn more here

- Swig Savvy’s Stainless Steel Insulated Water Bottle – Learn more here

Check Amazon’s best-seller list for the most popular travel accessories. We sometimes read this list just to find out what new travel products people are buying.

Beatrice is a vibrant content creator and recent law graduate residing in Nairobi, Kenya. Beyond the legal world, Beatrice has a true love for writing. Originally from the scenic county of Baringo, her journey weaves a rich tapestry of culture and experiences. Whether immersing herself in the bustling streets of Nairobi or reminiscing about her Baringo roots, her words paint vivid tales. She enjoys writing about law and literature, crafting a narrative that bridges her legal acumen, cultural heritage, and the sheer joy of putting pen to paper.

Hello & Welcome

Popular Articles

Top 20 Streets to See in Paris

Paris in two days

Top 15 Things to do Around the Eiffel Tower

The Best Way to Visit Paris Museums

Top 15 Fashion Stores in Le Marais

Visit europe with discover walks.

- Paris walking tours

- Montmartre walking tour

- Lisbon walking tours

- Prague walking tours

- Barcelona walking tours

- Private tours in Europe

- Privacy policy

© 2024 Charing Cross Corporation

We are a Parisian travel company so you will be getting tips on where to stay, what to see, restaurants and much more from local specialists!

No thanks, I’m not interested!

Social Psychology Experiments: 10 Of The Most Famous Studies

Ten of the most influential social psychology experiments explain why we sometimes do dumb or irrational things.

Ten of the most influential social psychology experiments explain why we sometimes do dumb or irrational things.

“I have been primarily interested in how and why ordinary people do unusual things, things that seem alien to their natures. Why do good people sometimes act evil? Why do smart people sometimes do dumb or irrational things?” –Philip Zimbardo

Like famous social psychologist Professor Philip Zimbardo (author of The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil ), I’m also obsessed with why we do dumb or irrational things.

The answer quite often is because of other people — something social psychologists have comprehensively shown.

Each of the 10 brilliant social psychology experiments below tells a unique, insightful story relevant to all our lives, every day.

Click the link in each social psychology experiment to get the full description and explanation of each phenomenon.

1. Social Psychology Experiments: The Halo Effect

The halo effect is a finding from a famous social psychology experiment.

It is the idea that global evaluations about a person (e.g. she is likeable) bleed over into judgements about their specific traits (e.g. she is intelligent).

It is sometimes called the “what is beautiful is good” principle, or the “physical attractiveness stereotype”.

It is called the halo effect because a halo was often used in religious art to show that a person is good.

2. Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort people feel when trying to hold two conflicting beliefs in their mind.

People resolve this discomfort by changing their thoughts to align with one of conflicting beliefs and rejecting the other.

The study provides a central insight into the stories we tell ourselves about why we think and behave the way we do.

3. Robbers Cave Experiment: How Group Conflicts Develop

The Robbers Cave experiment was a famous social psychology experiment on how prejudice and conflict emerged between two group of boys.

It shows how groups naturally develop their own cultures, status structures and boundaries — and then come into conflict with each other.

For example, each country has its own culture, its government, legal system and it draws boundaries to differentiate itself from neighbouring countries.

One of the reasons the became so famous is that it appeared to show how groups could be reconciled, how peace could flourish.

The key was the focus on superordinate goals, those stretching beyond the boundaries of the group itself.

4. Social Psychology Experiments: The Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford prison experiment was run to find out how people would react to being made a prisoner or prison guard.

The psychologist Philip Zimbardo, who led the Stanford prison experiment, thought ordinary, healthy people would come to behave cruelly, like prison guards, if they were put in that situation, even if it was against their personality.

It has since become a classic social psychology experiment, studied by generations of students and recently coming under a lot of criticism.

5. The Milgram Social Psychology Experiment

The Milgram experiment , led by the well-known psychologist Stanley Milgram in the 1960s, aimed to test people’s obedience to authority.

The results of Milgram’s social psychology experiment, sometimes known as the Milgram obedience study, continue to be both thought-provoking and controversial.

The Milgram experiment discovered people are much more obedient than you might imagine.

Fully 63 percent of the participants continued administering what appeared like electric shocks to another person while they screamed in agony, begged to stop and eventually fell silent — just because they were told to.

6. The False Consensus Effect

The false consensus effect is a famous social psychological finding that people tend to assume that others agree with them.

It could apply to opinions, values, beliefs or behaviours, but people assume others think and act in the same way as they do.

It is hard for many people to believe the false consensus effect exists because they quite naturally believe they are good ‘intuitive psychologists’, thinking it is relatively easy to predict other people’s attitudes and behaviours.

In reality, people show a number of predictable biases, such as the false consensus effect, when estimating other people’s behaviour and its causes.

7. Social Psychology Experiments: Social Identity Theory

Social identity theory helps to explain why people’s behaviour in groups is fascinating and sometimes disturbing.

People gain part of their self from the groups they belong to and that is at the heart of social identity theory.

The famous theory explains why as soon as humans are bunched together in groups we start to do odd things: copy other members of our group, favour members of own group over others, look for a leader to worship and fight other groups.

8. Negotiation: 2 Psychological Strategies That Matter Most

Negotiation is one of those activities we often engage in without quite realising it.

Negotiation doesn’t just happen in the boardroom, or when we ask our boss for a raise or down at the market, it happens every time we want to reach an agreement with someone.

In a classic, award-winning series of social psychology experiments, Morgan Deutsch and Robert Krauss investigated two central factors in negotiation: how we communicate with each other and how we use threats.

9. Bystander Effect And The Diffusion Of Responsibility

The bystander effect in social psychology is the surprising finding that the mere presence of other people inhibits our own helping behaviours in an emergency.

The bystander effect social psychology experiments are mentioned in every psychology textbook and often dubbed ‘seminal’.

This famous social psychology experiment on the bystander effect was inspired by the highly publicised murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964.

It found that in some circumstances, the presence of others inhibits people’s helping behaviours — partly because of a phenomenon called diffusion of responsibility.

10. Asch Conformity Experiment: The Power Of Social Pressure

The Asch conformity experiments — some of the most famous every done — were a series of social psychology experiments carried out by noted psychologist Solomon Asch.

The Asch conformity experiment reveals how strongly a person’s opinions are affected by people around them.

In fact, the Asch conformity experiment shows that many of us will deny our own senses just to conform with others.

Author: Dr Jeremy Dean

Psychologist, Jeremy Dean, PhD is the founder and author of PsyBlog. He holds a doctorate in psychology from University College London and two other advanced degrees in psychology. He has been writing about scientific research on PsyBlog since 2004. View all posts by Dr Jeremy Dean

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.

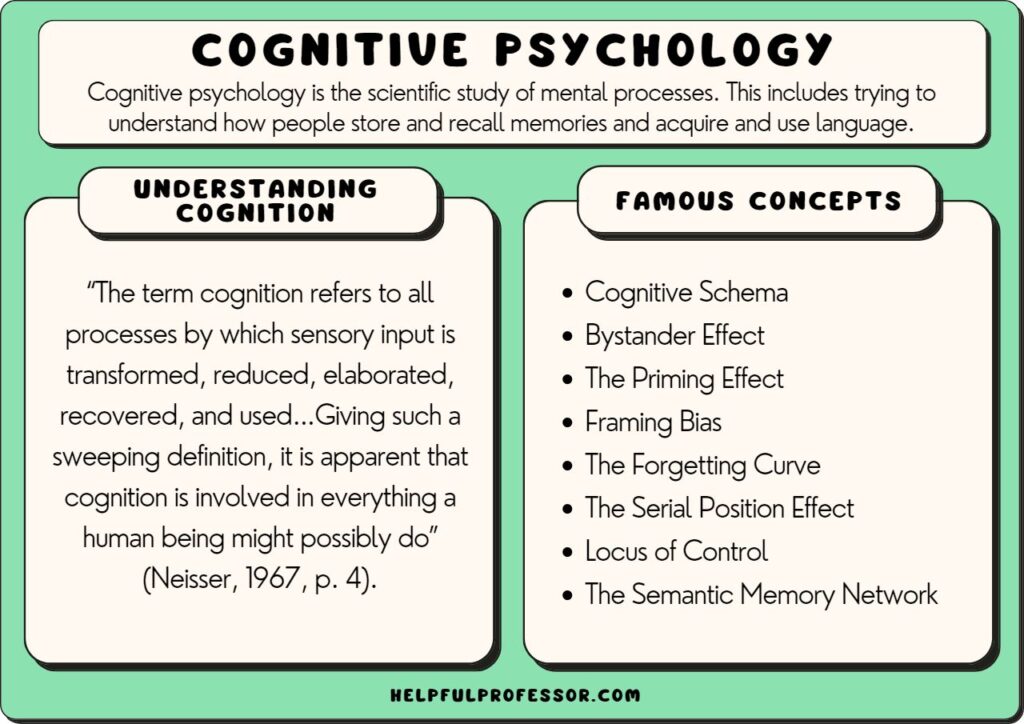

The 11 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History

The history of psychology is marked by groundbreaking experiments that transformed our understanding of the human mind. These 11 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History stand out as pivotal, offering profound insights into behaviour, cognition, and the complexities of human nature.

In this PsychologyOrg article, we’ll explain these key experiments, exploring their impact on our understanding of human behaviour and the intricate workings of the mind.

Table of Contents

Experimental psychology.

Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that uses scientific methods to study human behaviour and mental processes. Researchers in this field design experiments to test hypotheses about topics such as perception, learning, memory, emotion, and motivation.

They use a variety of techniques to measure and analyze behaviour and mental processes, including behavioural observations, self-report measures, physiological recordings, and computer simulations. The findings of experimental psychology studies can have important implications for a wide range of fields, including education, healthcare, and public policy.

Experimental Psychology, Psychologists have long tried to gain insight into how we perceive the world, to understand what motivates our behavior. They have made great strides in lifting that veil of mystery. In addition to providing us with food for stimulating party conversations, some of the most famous psychological experiments of the last century reveal surprising and universal truths about nature.

Throughout the history of psychology, revolutionary experiments have reshaped our comprehension of the human mind. These 11 experiments are pivotal, providing deep insights into human behaviour, cognition, and the intricate facets of human nature.

1. Kohler and the Chimpanzee experiment

Wolfgang Kohler studied the insight process by observing the behaviour of chimpanzees in a problem situation. In the experimental situation, the animals were placed in a cage outside of which food, for example, a banana, was stored. There were other objects in the cage, such as sticks or boxes. The animals participating in the experiment were hungry, so they needed to get to the food. At first, the chimpanzee used sticks mainly for playful activities; but suddenly, in the mind of the hungry chimpanzee, a relationship between sticks and food developed.

The cane, from an object to play with, became an instrument through which it was possible to reach the banana placed outside the cage. There has been a restructuring of the perceptual field: Kohler stressed that the appearance of the new behaviour was not the result of random attempts according to a process of trial and error. It is one of the first experiments on the intelligence of chimpanzees.

2. Harlow’s experiment on attachment with monkeys

In a scientific paper (1959), Harry F. Harlow described how he had separated baby rhesus monkeys from their mothers at birth, and raised them with the help of “puppet mothers”: in a series of experiments he compared the behavior of monkeys in two situations:

Little monkeys with a puppet mother without a bottle, but covered in a soft, fluffy, and furry fabric. Little monkeys with a “puppet” mother that supplied food, but was covered in wire. The little monkeys showed a clear preference for the “furry” mother, spending an average of fifteen hours a day attached to her, even though they were exclusively fed by the “suckling” puppet mother. conclusions of the Harlow experiment: all the experiments showed that the pleasure of contact elicited attachment behaviours, but the food did not.

3. The Strange Situation by Mary Ainsworth

Building on Bowlby’s attachment theory, Mary Ainsworth and colleagues (1978) have developed an experimental method called the Strange Situation, to assess individual differences in attachment security. The Strange Situation includes a series of short laboratory episodes in a comfortable environment and the child’s behaviors are observed.

Ainsworth and colleagues have paid special attention to the child’s behaviour at the time of reunion with the caregiver after a brief separation, thus identifying three different attachment patterns or styles, so called from that moment on. kinds of attachment according to Mary Ainsworth:

Secure attachment (63% of the dyads examined) Anxious-resistant or ambivalent (16%) Avoidant (21%) The Strange Situation by Mary Ainsworth

In a famous 1971 experiment, known as the Stanford Prison, Zimbardo and a team of collaborators reproduced a prison in the garages of Stanford University to study the behaviour of subjects in a context of very particular and complex dynamics. Let’s see how it went and the thoughts on the Stanford prison experiment. The participants (24 students) were randomly divided into two groups:

“ Prisoners “. The latter were locked up in three cells in the basement of a University building for six days; they were required to wear a white robe with a paper over it and a chain on the right ankle. “ Guards “. The students who had the role of prison guards had to watch the basement, choose the most appropriate methods to maintain order, and make the “prisoners” perform various tasks; they were asked to wear dark glasses and uniforms, and never to be violent towards the participants of the opposite role. However, the situation deteriorated dramatically: the fake police officers very soon began to seriously mistreat and humiliate the “detainees”, so it was decided to discontinue the experiment.

4. Jane Elliot’s Blue Eyes Experiment

On April 5, 1968, in a small school in Riceville, Iowa, Professor Jane Elliot decided to give a practical lesson on racism to 28 children of about eight years of age through the blue eyes brown eyes experiment.

“Children with brown eyes are the best,” the instructor began. “They are more beautiful and intelligent.” She wrote the word “melanin” on the board and explained that it was a substance that made people intelligent. Dark-eyed children have more, so they are more intelligent, while blue-eyed children “go hand in hand.”

In a very short time, the brown-eyed children began to treat their blue-eyed classmates with superiority, who in turn lost their self-confidence. A very good girl started making mistakes during arithmetic class, and at recess, she was approached by three little friends with brown eyes “You have to apologize because you get in their way and because we are the best,” said one of them. The girl hastened to apologize. This is one of the psychosocial experiments demonstrating how beliefs and prejudices play a role.

5. The Bobo de Bbandura doll

Albert Bandura gained great fame for the Bobo doll experiment on child imitation aggression, where:

A group of children took as an example, by visual capacity, the adults in a room, without their behaviour being commented on, hit the Bobo doll. Other contemporaries, on the other hand, saw adults sitting, always in absolute silence, next to Bobo.

Finally, all these children were brought to a room full of toys, including a doll like Bobo. Of the 10 children who hit the doll, 8 were those who had seen it done before by an adult. This explains how if a model that we follow performs a certain action, we are tempted to imitate it and this happens especially in children who still do not have the experience to understand for themselves if that behaviour is correct or not.

6. Milgram’s experiment

The Milgram experiment was first carried out in 1961 by psychologist Stanley Milgram, as an investigation into the degree of our deference to authority. A subject is invited to give an electric shock to an individual playing the role of the student, positioned behind a screen when he does not answer a question correctly. An authorized person then tells the subject to gradually increase the intensity of the shock until the student screams in pain and begs to stop.

No justification is given, except for the fact that the authorized person tells the subject to obey. In reality, it was staged: there was absolutely no electric shock given, but in the experiment two-thirds of the subjects were influenced by what they thought was a 450-volt shock, simply because a person in authority told them they would not be responsible for it. nothing.

7. little Albert

We see little Albert’s experiment on unconditioned stimulus, which must be the most famous psychological study. John Watson and Rosalie Raynor showed a white laboratory rat to a nine-month-old boy, little Albert. At first, the boy showed no fear, but then Watson jumped up from behind and made him flinch with a sudden noise by hitting a metal bar with a hammer. Of course, the noise frightened little Albert, who began to cry.

Every time the rat was brought out, Watson and Raynor would rattle the bar with their hammer to scare the poor boy away. Soon the mere sight of the rat was enough to reduce little Albert to a trembling bundle of nerves: he had learned to fear the sight of a rat, and soon afterwards began to fear a series of similar objects shown to him.

8. Pavlov’s dog

Ivan Pavlov’s sheepdog became famous for his experiments that led him to discover what we call “classical conditioning” or “Pavlovian reflex” and is still a very famous psychological experiment today. Hardly any other psychological experiment is cited so often and with such gusto as Pavlov’s theory expounded in 1905: the Russian physiologist had been impressed by the fact that his dogs did not begin to drool at the sight of food, but rather when they heard it. to the laboratory employees who took it away.

He researched it and ordered a buzzer to ring every time it was mealtime. Very soon the sound of the doorbell was enough for the dogs to start drooling: they had connected the signal to the arrival of food.

9. Asch’s experiment

It is about a social psychology experiment carried out in 1951 by the Polish psychologist Solomon Asch on the influence of the majority and social conformity.

The experiment is based on the idea that being part of a group is a sufficient condition to change a person’s actions, judgments, and visual perceptions. The very simple experiment consisted of asking the subjects involved to associate line 1 drawn on a white sheet with the corresponding one, choosing between three different lines A, B, and C present on another sheet. Only one was identical to the other, while the other two were longer or shorter.

The experimentation was carried out in three phases. As soon as one of the subjects, Asch’s accomplice gave a wrong answer associating line 1 with the wrong one, the other members of the group also made the same mistake, even though the correct answer was more than obvious. The participants questioned the reason for this choice and responded that aware of the correct answer, they had decided to conform to the group, adapting to those who had preceded them.

psychotherapy definition types and techniques | Psychotherapy vs therapy Psychologyorg.com

10. Rosenbaum’s experiment

Among the most interesting investigations in this field, an experiment carried out by David Rosenhan (1923) to document the low validity of psychiatric diagnoses stands out. Rosenhan admitted eight assistants to various psychiatric hospitals claiming psychotic symptoms, but once they entered the hospital they behaved as usual.

Despite this, they were held on average for 19 days, with all but one being diagnosed as “psychotic”. One of the reasons why the staff is not aware of the “normality” of the subjects, is, according to Rosenhan, the very little contact between the staff and the patients.

11. Bystander Effect (1968)

The Bystander Effect studied in 1968 after the tragic case of Kitty Genovese, explores how individuals are less likely to intervene in emergencies when others are present. The original research by John Darley and Bibb Latané involved staged scenarios where participants believed they were part of a discussion via intercom.

In the experiment, participants were led to believe they were communicating with others about personal problems. Unknown to them, the discussions were staged, and at a certain point, a participant (confederate) pretended to have a seizure or needed help.

The results were startling. When participants believed they were the sole witness to the emergency, they responded quickly and sought help. However, when they thought others were also present (but were confederates instructed to not intervene), the likelihood of any individual offering help significantly decreased. This phenomenon became known as the Bystander Effect.

The diffusion of responsibility, where individuals assume others will take action, contributes to this effect. The presence of others creates a diffusion of responsibility among bystanders, leading to a decreased likelihood of any single individual taking action.

This experiment highlighted the social and psychological factors influencing intervention during emergencies and emphasized the importance of understanding bystander behaviour in critical situations.

The journey through the “11 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History” illuminates the profound impact these studies have had on our understanding of human behaviour, cognition, and social dynamics.

Each experiment stands as a testament to the dedication of pioneering psychologists who dared to delve into the complexities of the human mind. From Milgram’s obedience studies to Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment, these trials have shaped not only the field of psychology but also our societal perceptions and ethical considerations in research.

They serve as timeless benchmarks, reminding us of the ethical responsibilities and the far-reaching implications of delving into the human psyche. The enduring legacy of these experiments lies not only in their scientific contributions but also in the ethical reflections they provoke, urging us to navigate the boundaries of knowledge with caution, empathy, and an unwavering commitment to understanding the intricacies of our humanity.

What is the most famous experiment in the history of psychology?

One of the most famous experiments is the Milgram Experiment, conducted by Stanley Milgram in the 1960s. It investigated obedience to authority figures and remains influential in understanding human behaviour.

Who wrote the 25 most influential psychological experiments in history?

The book “The 25 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History” was written by Michael Shermer, a science writer and historian of science.

What is the history of experimental psychology?

Experimental psychology traces back to Wilhelm Wundt, often considered the father of experimental psychology. He established the first psychology laboratory in 1879 at the University of Leipzig, marking the formal beginning of experimental psychology as a distinct field.

What was the psychological experiment in the 1960s?

Many significant psychological experiments were conducted in the 1960s. One notable example is the Stanford Prison Experiment led by Philip Zimbardo, which examined the effects of situational roles on behaviour.

Who was the first experimental psychologist?

Wilhelm Wundt is often regarded as the first experimental psychologist due to his establishment of the first psychology laboratory and his emphasis on empirical research methods in psychology.

If you want to read more articles similar to The 11 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History , we recommend that you enter our Psychology category.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Random article

- Teaching guide

- Privacy & cookies

10 great psychology experiments

by Chris Woodford . Last updated: December 31, 2021.

S tare in the mirror and you'll find a strong sense of self staring back. Every one of us thinks we have a good idea who we are and what we're about—how we laugh and live and love, and all the complicated rest. But if you're a student of psychology —the fascinating science of human behaviour—you may well stare at your reflection with a wary eye. Because you'll know already that the ideas you have about yourself and other people can be very wide of the mark.

You might think you can learn a lot about human behaviour simply by observing yourself, but psychologists know that isn't really true. "Introspection" (thinking about yourself) has long been considered a suspect source of psychological research, even though one of the founding fathers of the science, William James, gained many important insights with its help. [1] Fortunately, there are thousands of rigorous experiments you can study that will do the job much more objectively and scientifically. And here's a quick selection of 10 of my favourites.

Listen instead... or scroll to keep reading

1: are you really paying attention (simons & chabris, 1999).

“ ...our findings suggest that unexpected events are often overlooked... ” Simons & Chabris, 1999

You can read a book or you can listen to the radio, but can you do both at once? Maybe you can listen to a soft-rock album you've heard hundreds of times before and simultaneously plod your way through an undemanding crime novel, but how about listening to a complex political debate while trying to revise for a politics exam? What about listening to a German radio station while reading a French novel? What about mixing things up a bit more. You can iron your clothes while listening to the radio, no problem. But how about trying to follow (and visualize) the radio commentary on a football game while driving a highway you've never been along before? That's much more challenging because both things call on your brain's ability to process spatial information and one tends to interfere with the other. (There are very good reasons why it's unwise to use a cellphone while you're driving—and in some countries it's illegal.)

Generally speaking, we can do—and pay attention—to only so many things at once. That's no big surprise. However human attention works (and there are many theories about that), it's obviously not unlimited. What is surprising is how we pay attention to some things, in some situations, but not others. Psychologists have long studied something they call the cocktail-party effect . If you're at a noisy party, you can selectively switch your attention to any of the voices around you, just like tuning in a radio, while ignoring all the rest. Even more striking, if you're listening to one person and someone else happens to say your name, your ears will prick up and your attention will instantly switch to the other person instead. So your brain must be aware of much more than you think, even if it's not giving everything its full attention, all the time. [2]

Photo: Would you spot a gorilla if it were in plain sight? Picture by Richard Ruggiero courtesy of US Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library .

Sometimes, when we're really paying attention, we aren't easily distracted, even by drastic changes we ought to notice. A particularly striking demonstration of this comes from the work of Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris (1999), who built on earlier work by the esteemed cognitive psychologist Ulric Neisser and colleagues. [3] Simons and Chabris made a video of people in black or white shirts throwing a basketball back and forth and asked viewers to count the number of passes made by the white-shirted players. You can watch it here .

Half the viewers failed to notice something else that happens at the same time (the gorilla-suited person wandering across the set)—an extraordinary example of something psychologists call inattentional blindness (in plain English: failure to see something you really should have spotted). A related phenomenon called change blindness explains why we generally fail to notice things like glaring continuity errors in movies: we don't expect to see them—and so we don't. Whether experiments like "the invisible gorilla" allow us to conclude broader things about human nature is a moot point, but it's certainly fair to say (as Simons and Chabris argue) that they reveal "critically important limitations of our cognitive abilities." None of us are as smart as we like to think, but just because we fail and fall short that doesn't make us bad people; we'd do a lot better if we understood and recognized our shortcomings. [4]

2: Are you trying too hard? (Aronson, 1966)

No-one likes a smart-aleck, so the saying goes, but just how true is that? Even if you really hate someone who has everything—the good looks, the great house, the well-paid job—it tuns out that there are certain circumstances in which you'll like them a whole lot more: if they suddenly make a stupid mistake. This not-entirely-surprising bit of psychology mirrors everyday experience: we like our fellow humans slightly flawed, down-to-earth, and somewhat relatable. Known as the pratfall effect , it was famously demonstrated back in 1966 by social psychologist Elliot Aronson. [5]

“ ...a superior person may be viewed as superhuman and, therefore, distant; a blunder tends to humanize him and, consequently, increases his attractiveness. ” Aronson et al, 1966

Aronson made taped audio recordings of two very different people talking about themselves and answering 50 difficult questions, which were supposedly part of an interview for a college quiz team. One person was very superior, got almost all the questions right, and revealed (in passing) that they were generally excellent at what they did (an honors student, yearbook editor, and member of the college track team). The other person was much more mediocre, got many questions wrong, and revealed (in passing) that they were much more of a plodder (average grades in high school, proofreader of the yearbook, and failed to make the track team). In the experiment, "subjects" (that's what psychologists call the people who take part in their trials) had to listen to the recordings of the two people and rate them on various things, including their likeability. But there was a twist. In some of the taped interviews, an extra bit (the "pratfall") was added at the end where either the superior person or the mediocrity suddenly shouted "Oh my goodness I've spilled coffee all over my new suit", accompanied by the sounds of a clattering chair and general chaos (noises that were identically spliced onto both tapes).

Artwork: Mistakes make you more likeable—if you're considered competent to begin with.

What Aronson found was that the superior person was rated more attractive with the pratfall at the end of their interview; the inferior person, less so. In other words, a pratfall can really work in your favor, but only if you're considered halfway competent to begin with; if not, it works against you. Knowingly or otherwise, smart celebrities and politicians often appear to take advantage of this to improve their popularity.

3: Is the past a foreign country? (Loftus and Palmer, 1974)

Attention isn't the only thing that lets us down; memory is hugely infallible too—and it's one of the strangest and most complex things psychologists study. Can you remember where you were when the Twin Towers fell in 2001 or (if you're much older and willing to go back further) when JFK was shot in Dallas in 1963? You might remember a girl you were in kindergarten with 20 years ago, but perhaps you can't remember the guy you met last week, last night, or even 10 minutes ago. What about the so-called tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon where you're certain you know a word or fact or name, and you can even describe what it's like ("It's a really short word, maybe beginning with 'F'..."), but you can't bring it instantly to mind? [6] How about the madeleine effect, where the taste or smell or something suddenly sets off an incredibly powerful involuntary memory ? What about déjà-vu : a jarring true-false memory—the strong sense something is very familiar when it can't possibly be? [7] How about the curious split between short- and long-term memories or between "procedural memory" (knowing how to do things or follow instructions) and "declarative memory" (knowing facts), which breaks down further into "semantic memory" (general knowledge about things) and "episodic memory" (specific things that have happened to you). What about the many flavors of selective memory failure, such as seniors who can remember the name of a high-school sweetheart but can't recall their own name? Or sudden episodes of amnesia? Human memory is a massive—and massively complex—subject. And any comprehensive theory of it needs to be able to explain a lot.

“ ...the questions asked subsequent to an event can cause a reconstruction in one's memory of that event.. ” Loftus & Palmer, 1974

Much of the time, poor memory is just a nuisance and we all have tricks for working around it—from slapping Post-It notes on the mirror to setting reminders on our phones. But there's one situation where poor memories can be a matter of life or death: in criminal investigation and court testimony. Suppose you give evidence in a trial based on events you think you remember that happened years ago—and suppose your evidence helps to convict a "murderer" who's subsequently sentenced to death. But what if your memory was quite wrong and the person was innocent?

One of the most famous studies of just how flawed our memories can be was made by psychologists Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer in 1974. [8] After showing their subjects footage of a car accident, they tested their memories some time later by asking "About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?" or using "collided," "bumped," "contacted," or "hit" in place of smashed. Those asked the first—leading—question reported higher speeds. Later, the subjects were asked if they'd seen any broken glass and those asked the leading question ("smashed") were much more likely to say "yes" even though there was no broken glass in the film. So our memories are much more fluid, far less fixed, than we suppose.

Artwork: The words we use to probe our memories can affect the memories we think we have.

This classic experiment very powerfully illustrates the potential unreliability of eyewitness testimony in criminal investigations, but the work of Elizabeth Loftus on so-called "false memory syndrome" has had far-reaching impacts in provocative areas, such as people's alleged recollections of alien abduction , multiple personality disorder , and memories of childhood abuse . Ultimately, what it demonstrates is that memory is fallible and remembering is sometimes less of a mechanical activity (pulling a dusty book from long-neglected library shelf) than a creative and recreative one (rewriting the book partly or completely to compensate for the fact that the print has faded with time). [9]

4. Do you cave in to peer pressure? (Milgram, 1963)

Experiments like the three we've considered so far might cast an uncomfortable shadow, yet most of us are still convinced we're rational, reasonable people, most of the time. Asked to predict how we'd behave in any given situation, we'd be able to give a pretty good account of ourselves—or so you might think. Consider the question of whether you'd ever, under any circumstances, torture another human being and you'd probably be appalled at the prospect. "Of course not!" And yet, as Yale University's Stanley Milgram famously demonstrated in the 1960s and 1970s, you'd probably be mistaken. [10]

Artwork: The Milgram experiment: a shocking turn of events.