Planning your PhD research: A 3-year PhD timeline example

Planning out a PhD trajectory can be overwhelming. Example PhD timelines can make the task easier and inspire. The following PhD timeline example describes the process and milestones of completing a PhD within 3 years.

Elements to include in a 3-year PhD timeline

The example scenario: completing a phd in 3 years, example: planning year 1 of a 3-year phd, example: planning year 2 of a 3-year phd, example: planning year 3 of a 3-year phd, example of a 3 year phd gantt chart timeline, final reflection.

Every successful PhD project begins with a proper plan. Even if there is a high chance that not everything will work out as planned. Having a well-established timeline will keep your work on track.

What to include in a 3-year PhD timeline depends on the unique characteristics of a PhD project, specific university requirements, agreements with the supervisor/s and the PhD student’s career ambitions.

For instance, some PhD students write a monograph while others complete a PhD based on several journal publications. Both monographs and cumulative dissertations have advantages and disadvantages , and not all universities allow both formats. The thesis type influences the PhD timeline.

Furthermore, PhD students ideally engage in several different activities throughout a PhD trajectory, which link to their career objectives. Regardless of whether they want to pursue a career within or outside of academia. PhD students should create an all-round profile to increase their future chances in the labour market. Think, for example, of activities such as organising a seminar, engaging in public outreach or showcasing leadership in a small grant application.

The most common elements included in a 3-year PhD timeline are the following:

- Data collection (fieldwork, experiments, etc.)

- Data analysis

- Writing of different chapters, or a plan for journal publication

- Conferences

- Additional activities

The whole process is described in more detail in my post on how to develop an awesome PhD timeline step-by-step .

Many (starting) PhD students look for examples of how to plan a PhD in 3 years. Therefore, let’s look at an example scenario of a fictional PhD student. Let’s call her Maria.

Maria is doing a PhD in Social Sciences at a university where it is customary to write a cumulative dissertation, meaning a PhD thesis based on journal publications. Maria’s university regulations require her to write four articles as part of her PhD. In order to graduate, one article has to be published in an international peer-reviewed journal. The other three have to be submitted.

Furthermore, Maria’s cumulative dissertation needs an introduction and conclusion chapter which frame the four individual journal articles, which form the thesis chapters.

In order to complete her PhD programme, Maria also needs to complete coursework and earn 15 credits, or ECTS in her case.

Maria likes the idea of doing a postdoc after her graduation. However, she is aware that the academic job market is tough and therefore wants to keep her options open. She could, for instance, imagine to work for a community or non-profit organisation. Therefore, she wants to place emphasis on collaborating with a community organisation during her PhD.

You may also like: Creating awesome Gantt charts for your PhD timeline

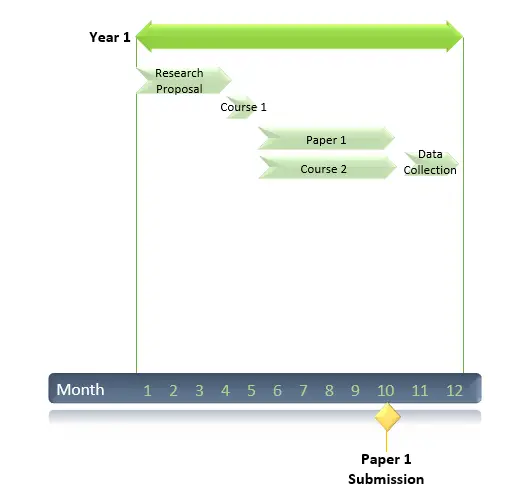

Most PhD students start their first year with a rough idea, but not a well-worked out plan and timeline. Therefore, they usually begin with working on a more elaborate research proposal in the first months of their PhD. This is also the case for our example PhD student Maria.

- Months 1-4: Maria works on a detailed research proposal, defines her research methodology and breaks down her thesis into concrete tasks.

- Month 5 : Maria follows a short intensive course in academic writing to improve her writing skills.

- Months 5-10: Maria works on her first journal paper, which is based on an extensive literature review of her research topic. At the end of Month 10, she submits the manuscript. At the same time, she follows a course connected to her research topic.

- Months 11-12: Maria does her data collection.

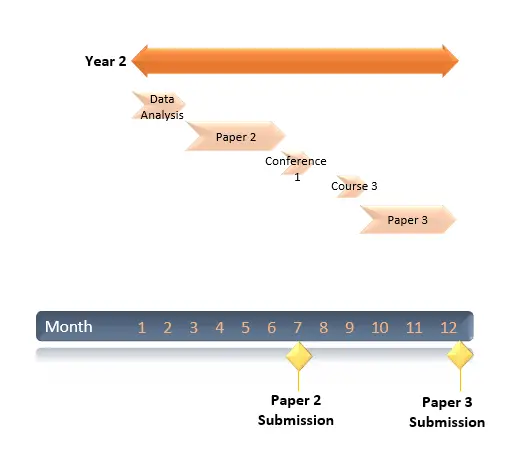

Maria completed her first round of data collection according to plan, and starts the second year of her PhD with a lot of material. In her second year, she will focus on turning this data into two journal articles.

- Months 1-2: Maria works on her data analysis.

- Months 3-7: Maria works on her second journal paper.

- Month 7: Maria attends her first conference, and presents the results of her literature-review paper.

- Month 8: Maria received ‘major revisions’ on her first manuscript submission, and implements the changes in Month 8 before resubmitting her first journal paper for publication.

- Month 9: Maria follows a course on research valorisation to learn strategies to increase the societal impact of her thesis.

- Months 9-12: Maria works on her third journal paper. She uses the same data that she collected for the previous paper, which is why she is able to complete the third manuscript a bit faster than the previous one.

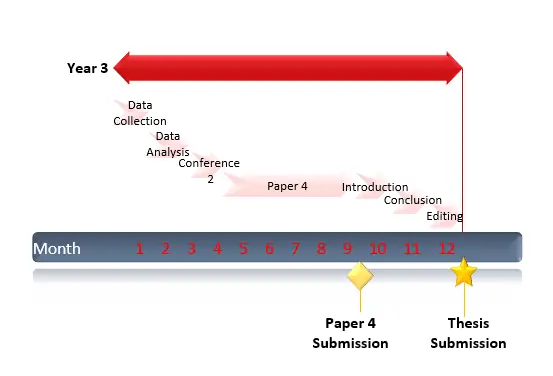

Time flies, and Maria finds herself in the last year of her PhD. There is still a lot of work to be done, but she sticks to the plan and does her best to complete her PhD.

- Month 1: Maria starts a second round of data collection, this time in collaboration with a community organisation. Together, they develop and host several focus groups with Maria’s target audience.

- Month 2: Maria starts to analyse the material of the focus group and develops the argumentation for her fourth journal paper.

- Month 3: Maria presents the results of her second journal paper at an international conference. Furthermore, she helps out her supervisor with a grant application. They apply for funding to run a small project that is thematically connected to her PhD.

- Months 4-9: Maria writes her fourth and final journal article that is required for her PhD.

- Month 10: Maria writes her thesis introduction .

- Month 11: Maria works on her thesis conclusion.

- Month 12 : Maria works on the final edits and proof-reading of her thesis before submitting it.

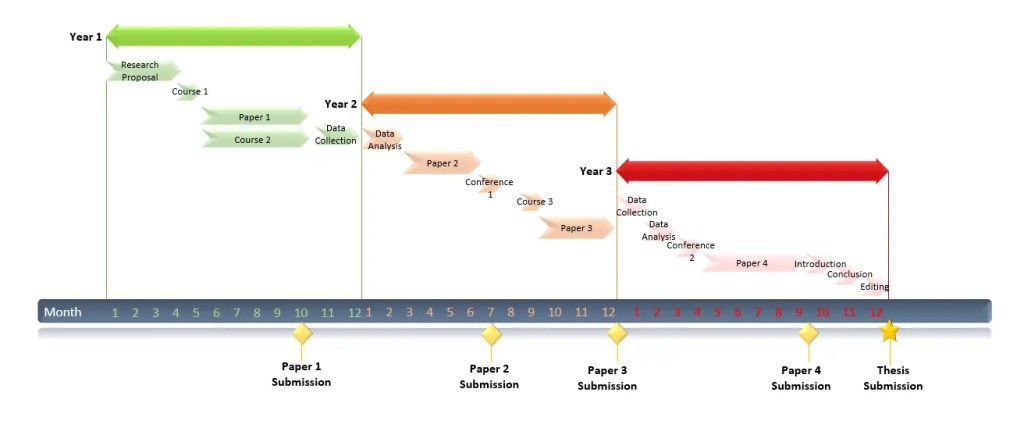

Combining the 3-year planning for our example PhD student Maria, it results in the following PhD timeline:

Creating these PhD timelines, also called Gantt charts, is easy. You can find instructions and templates here.

Completing a PhD in 3 years is not an easy task. The example of our fictional PhD student Maria shows how packed her timeline is, and how little time there is for things to go wrong.

In fact, in real life, many PhD students spend four years full-time to complete a PhD based on four papers, instead of three. Some extend their studies even longer.

Furthermore, plan in some time for thesis editing, which is a legitimate practice and can bring your writing to the next level. Finding a reputable thesis editor can be challenging, so make sure you make an informed choice.

Finishing a PhD in 3 years is not impossible, but it surely is not easy. So be kind to yourself if things don’t work out entirely as planned, and make use of all the help you can get.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

10 amazing benefits of getting a PhD later in life

How to prepare your viva opening speech, related articles.

Sample emails asking for letter of recommendation from a professor

Funding sources for PhD studies in Europe

The best answers to “What are your plans for the future?”

25 short graduation quotes: Inspiration in four words or less

- eSignatures

- Product updates

- Document templates

How to nail your PhD proposal and get accepted

Bethany Fagan Head of Content Marketing at PandaDoc

Reviewed by:

Olga Asheychik Senior Web Analytics Manager at PandaDoc

- Copy Link Link copied

A good PhD research proposal may be the deciding factor between acceptance and approval into your desired program or finding yourself back at the drawing board. Being accepted for a PhD placement is no easy task, and this is why your PhD proposal needs to truly stand out among a sea of submissions.

That’s why a PhD research proposal is important: It formally outlines the intended research, including methodology, timeline, feasibility, and many other factors that need to be taken into consideration.

Here is a closer look at the PhD proposal process and what it should look like.

→DOWNLOAD NOW: FREE PHD PROPOSAL TEMPLATE

Key takeaways

- A PhD proposal summarizes the research project you intend to conduct as part of your PhD program.

- These proposals are relatively short (1000-2000 words), and should include all basic information and project goals, including the methodologies/strategies you intend to use in order to accomplish them.

- Formats are varied. You may be able to create your own formats, but your college or university may have a required document structure that you should follow.

What is a PhD proposal?

In short, a PhD research proposal is a summary of the project you intend to undertake as part of your PhD program.

It should pose a specific question or idea, make a case for the research, and explain the predicted outcomes of that research.

However, while your PhD proposal may predict expected outcomes, it won’t fully answer your questions for the reader.

Your research into the topic will provide that answer.

Usually, a PhD proposal contains the following elements:

- A clear question that you intend to answer through copious amounts of study and research.

- Your plan to answer that question, including any methodologies, frameworks, and resources required to adequately find the answer.

- Why your question or project is significant to your specific field of study.

- How your proposal impacts, challenges, or improves the existing body of knowledge around a given topic.

- Why your work is important and why you should be the one to receive this opportunity.

In terms of length when writing a PhD proposal, there isn’t a universal answer.

Some institutions will require a short, concise proposal (1000 words), while others allow for a greater amount of flexibility in the length and format of the proposal.

Fortunately, most institutions will provide some guidelines regarding the format and length of your research proposal, so you should have a strong idea of your requirements before you begin.

Benefits of a strong PhD application

While the most obvious benefit of having a strong PhD application is being accepted to the PhD program , there are other reasons to build the strongest PhD application you can:

Better funding opportunities

Many PhD programs offer funding to students , which can be used to cover tuition fees and may provide a stipend for living expenses.

The stronger your PhD application, the better your chances of being offered funding opportunities that can alleviate financial burdens and allow you to focus on your research.

Enhanced academic credentials

A strong PhD application, particularly in hot-button areas of study, can lead to better career opportunities in academics or across a variety of industries.

Opportunities for networking and research

Research proposals that are very well grounded can provide footholds to networking opportunities and mentorships that would not be otherwise available.

However, creating an incredible proposal isn’t always easy.

In fact, it’s easy to get confused by the process since it requires a lot of procedural information.

Many institutions also place a heavy emphasis on using the correct proposal structure.

That doesn’t have to be the issue, though.

Often, pre-designed templates, like the PandaDoc research proposal templates or PhD proposal templates provided by the institution of your choice, can do most of the heavy lifting for you.

Research Proposal Template

Used 7990 times

4.1 rating (31 reviews)

Reviewed by Olga Asheychik

How to write a Phd proposal with a clear structure

We know that the prospect of writing a research proposal for PhD admission may appear the stuff of nightmares. Even more so if you are new to producing a piece such as this.

But, when you get down to the nitty gritty of what it is, it really isn’t so intimidating. When writing your PhD proposal you need to show that your PhD is worth it, achievable, and that you have the ability to do it at your chosen university.

With all of that in mind, let’s take a closer look at each section of a standard PhD research proposal and the overall structure.

1. Front matter

The first pages of your PhD proposal should outline the basic information about the project. That will include each of the following:

Project title

Typically placed on the first page, your title should be engaging enough to attract attention and clear enough that readers will understand what you’re trying to achieve.

Many proposals also include a secondary headline to further (concisely) clarify the main concept.

Contact information

Depending on the instructions provided by your institution, you may need to include your basic contact information with your proposal.

Some institutions may ask for blind submissions and ask that you omit identifying information, so check the program guidelines to be sure.

Research supervisor

If you already have a supervisor for the project, you’ll typically want to list that information.

Someone who is established in the field can add credibility to your proposal, particularly if your project requires extensive funding or has special considerations.

The guidelines from your PhD program should provide some guidance regarding any other auxiliary information that you should add to the front of your proposal.

Be sure to check all documentation to ensure that everything fits into the designated format.

2. Goals, summaries, and objectives

Once you’ve added the basic information to your document, you’ll need to get into the meat of your PhD proposal.

Depending on your institution, your research proposal may need to follow a rigid format or you may have the flexibility to add various sections and fully explain your concepts.

These sections will primarily be focused on providing high-level overviews surrounding your PhD proposal, including most of the following:

Overall aims, objectives, and goals

In these sections, you’ll need to state plainly what you aim to accomplish with your PhD research.

If awarded funding, what questions will your PHd proposal seek to answer? What theories will you test? What concepts will you explore in your research?

Briefly, how would you summarize your approach to this project?

Provide high-level summaries detailing how you mean to achieve your answers, what the predicted outcomes of your PhD research might be, and precisely what you intend to test or discover.

Significance

Why does your research matter? Unlike with many other forms of academic study (such as a master’s thesis ), doctorate-level research often pushes the bounds of specific fields or contributes to a given body of work in some unique way.

How will your proposed PhD research do those things?

Background details

Because PhD research is about pushing boundaries, adding background context regarding the current state of affairs in your given field can help readers better understand why you want to pursue this research and how you arrived at this specific point of interest.

While the information here may (or may not) be broken into multiple sections, the content here is largely designed to provide a high-level overview of your PhD proposal and entice readers to dig deeper into the methodologies and angles of approach in future sections.

Because so much of this section relies on the remainder of your document, it’s sometimes better to skip this portion of the PhD proposal until the later sections are complete and then circle back to it.

That way, you can provide concise summaries that refer to fully defined research methods that you’ve already explained in subsequent areas.

3. Methodologies and plans

Unlike a master’s thesis or a similar academic document, PhD research is designed to push the boundaries of its subject matter in some way.

The idea behind doctoral research is to expand the field with new insights and viewpoints that are the culmination of years of research and study, combined with a deep familiarity of the topic at hand.

The methodologies and work plans you provide will give advisors some insights into how you plan to conduct your research.

While there is no one right way to develop this section, you’ll need to include a few key details:

Research methods

Are there specific research methods you plan to use to conduct your PhD research?

Are you conducting experiments? Conducting qualitative research? Surveying specific individuals in a given environment?

Benefits and drawbacks of your approach

Regardless of your approach to your topic, there will be upsides and downsides to that methodology.

Explain what you feel are the primary benefits to your research method, where there are potential flaws, and how you plan to account for those shortfalls.

Choice of methodology

Why did you choose a given methodology?

What makes it the best method (or collection of methods) for your research and/or specific use case?

Outline of proposed work

What work is required for PhD research to be complete?

What steps will you need to take in order to capture the appropriate information? How will you complete those steps?

Schedule of work (including timelines/deadlines)

How long will it take you to complete each stage or step of your project?

If your PhDproject will take several years, you may need to provide specifics for more immediate timelines up front while future deadlines may be flexible or estimated.

There is some flexibility here.

It’s unlikely that your advisors will expect you to have the answer for every question regarding how you plan to approach your body of research.

When trying to push the boundaries of any given topic, it’s expected that some things may not go to plan.

However, you should do your best to make timelines and schedules of work that are consistent with your listed goals.

Remember : At the end of your work, you are expected to have a body of original research that is complete within the scope and limitations of the PhD proposal you set forth.

If your advisors feel that your subject matter is too broad, they may encourage you to narrow the scope to better fit into more standardized expectations.

4. Resources and citations

No PhD research proposal is complete without a full list of the resources required to carry out the project and references to help prove and validate the research.

Here’s a closer look at what you’ll need to submit in order to explain costs and prove the validity of your proposal:

Estimated costs and resources

Most doctoral programs offer some level of funding for these projects.

To take advantage of those funds, you’ll need to submit a budget of estimated costs so that assessors can better understand the financial requirements.

This might include equipment, expenses for fieldwork or travel, and more.

Citations and bibliographies

No matter your field of study, doctoral research is built on the data and observations provided by past contributors.

Because of this, you’ll need to provide citations and sources referenced in your PhD proposal documentation.

Particularly when it comes to finances and funding, it might be tempting to downplay the cost of the project.

However, it’s best to provide a realistic estimate in terms of costs so that you have enough of a budget to cover the PhD research.

Adjustments can be made at a later date, particularly as you conduct more research and dive further into the project.

Resources are often presented in the form of a table to make things easier to track and identify.

Using PhD proposal templates

Aside from any guidelines set forth by your institution, there are no particularly strict rules when it comes to the format of PhD proposals.

Your supervisor will be more than capable of guiding you through the process.

However, since everything is so structured and formal, you might want to use a PhD proposal template to help you get started.

Templates can help you stay on track and make sure your research proposal follows a certain logic.

A lot of proposal software solutions offer templates for different types of proposals, including PhD proposals.

But, should you use Phd proposal templates? Here are some pros and cons to help you make a decision.

- Expedites the proposal process.

- Helps you jumpstart the process with a flexible document structure.

- Often provides sections with pre-filled examples.

- Looks better than your average Word document.

- May be limiting if you adhere to it too much.

- Might not be perfectly suited to your specific field of research, requiring some customization.

In our PhD research proposal template , we give you just enough direction to help you follow through but we don’t limit your creativity to a point that you can’t express yourself and all the nuances of your research.

For almost all sections, you get a few useful PhD research proposal examples to point you in the right direction.

The template provides you with a typical PhD proposal structure that’s perfect for almost all disciplines.

It can come in quite handy when you have everything planned out in your head but you’re just having trouble putting it onto the page!

Writing a PhD proposal that convinces

Writing and completing a PhD proposal might be confusing at first.

You need to follow a certain logic and share all the required information without going too long or sharing too much about the project.

And, while your supervisor will certainly be there to guide you, the brunt of the work will still fall on your shoulders.

That’s why you need to stay informed, do your research, and don’t give up until you feel comfortable with what you’ve created.

If you want to get a head start, you might want to consider our research proposal template .

It will offer you a structure to follow when writing a PhD proposal and give you an idea on what to write in each section.

Start your 14 days trial with PandaDoc and check out all the tools you’ll have at your disposal!

Research proposals for PhD admission: tips and advice

One of the most important tips for any piece of writing is to know your audience. The staff reviewing your PhD proposal are going through a pile of them, so you need to make sure yours stands within a few seconds of opening it.

The way to do this is by demonstrating value and impact. Academic work is often written for a niche community of researchers in one field, so you need to demonstrate why your work would be valuable to people in that area.

The people reviewing your proposal will likely be in that field. So your proposal should be a little like a sales pitch: you need to write something engaging that identifies with the “customer”, speaks to a problem they’re having, and shows them a solution.

Taking some inspiration from the former University of Chicago professor Larry McEnerney , here are some ideas to keep in mind…

- It’s common for undergraduates and even seasoned academics to write in a specific format or style to demonstrate their understanding and signal that they’re part of the academic community. Instead, you want to write in such a way that actually engages the reader.

- Identify an uncharted or underexplored knowledge gap in your field, and show the reader you have what it takes to fill in that gap.

- Challenge the status quo. Set up an idea that people in your field take for granted — maybe a famous study you think is flawed — and outline how your project could knock it down.

- This is why it’s important to understand who your audience is. You have to write your proposal in such a way that it’s valuable for reviewers. But within your proposal, you should also clearly define which community of researchers your project is for, what problems they have, and how your project is going to solve those problems.

- Every community of researchers has their own implicit “codes” and “keywords” that signal understanding. These will be very different in each field and could be very subtle. But just by reading successful PhD research proposal examples in your field, you can get a sense of what those are and decide how you want to employ them in your own work.

- In this model authors start “at the bottom of the glass” with a very narrow introduction to the idea of the paper, then “fill the glass” with a broader and broader version of the same idea.

- Instead, follow a “problem-solution” framework. Introduce a problem that’s relevant to your intended reader, then offer a solution. Since “solutions” often raise their own new problems or questions, you can rinse and repeat this framework all the way through any section of your proposal.

But how can you apply that advice? If you’re following something like our research proposal template , here are some actionable ways to get started.

- Your title should be eye-catching , and signal value by speaking to either a gap in the field or challenging the status quo.

- Your abstract should speak to a problem in the field, one the reviewers will care about, and clearly outline how you’d like to solve it.

- When you list the objectives of your proposal , each one should repeat this problem-solution framework. You should concretely state what you want to achieve, and what you’re going to do to achieve it.

- While you survey your chosen field in the literature review, you should refer back to the knowledge gap or status quo that you intend to work on. This reinforces how important your proposed project is, and how valuable it would be to the community if your project was successful.

- While listing your research limitations , try to hint at new territory researchers might be able to explore off the back of your work. This illustrates that you’re proposing boundary-pushing work that will really advance knowledge of the field.

- While you’re outlining your funding requirements , be clear about why each line item is necessary and bring it back to the value of your proposed research. Every cent counts!

Frequently asked questions

How long should a phd proposal be.

There really isn’t a specific rule when it comes to the length of a PhD proposal. However, it’s generally accepted that it should be between 1,000 and 2,000 words.

It’s difficult to elaborate on such a serious project in less than 1,000 words but going over 2,000 is often overkill. You’ll lose people’s attention and water down your points.

What’s the difference between a dissertation proposal and a PhD proposal?

There seems to be some confusion over the terms “dissertation” and “PhD” and how you write proposals for each one. However, “dissertation” is just another name for your PhD research so the proposal for a dissertation would be the same since it’s quite literally the same thing.

Does a PhD proposal include budgeting?

Yes, as mentioned, you need to demonstrate the feasibility of your project within the given time frame and with the resources you need, including budgets. You don’t need to be exact, but you need to have accurate estimates for everything.

How is a PhD proposal evaluated?

This will change from one institution to another but these things will generally have a big impact on the reviewers:

- The contribution of the project to the field.

- Design and feasibility of the project.

- The validity of the methodology and objectives.

- The supervisor and their role in the field.

PandaDoc is not a law firm, or a substitute for an attorney or law firm. This page is not intended to and does not provide legal advice. Should you have legal questions on the validity of e-signatures or digital signatures and the enforceability thereof, please consult with an attorney or law firm. Use of PandaDocs’ services are governed by our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Originally published June 9, 2023, updated February 6, 2024

Reviewed by

Streamline your document workflow & close deals faster

Get personalized 1:1 demo with our product specialist.

- Tailored to your needs

- Answers all your questions

- No commitment to buy

- Fill out the form

- Book a time slot

- Attend a demo

By submitting this form, I agree that the Terms of Service and Privacy Notice will govern the use of services I receive and personal data I provide respectively.

Related articles

Proposals 24 min

Sales 5 min

Document templates 13 min

PhD Research Proposal Template With Examples

23/02/2023 (updated 13/09/2023) Emily Watson

A comprehensive research proposal is one of the most important parts of your PhD application, as it explains what you plan to research, what your aims and objectives are, and how you plan to meet those objectives.

Below you will find a research proposal template you can use to write your own PhD proposal, along with examples of specific sections. Note that your own research proposal should be specific and carefully tailored to your own project and no two proposals look the same. Use the template and examples below with that in mind.

If you’re looking for more detailed information on how to write a PhD research proposal, read our full guide via the button below.

How to write a PhD research proposal

Research Proposal Template

The template below is one way you could consider structuring your research proposal to ensure that you include all of the relevant information about your project. However, each university publishes its own guidance on what to include in a proposal, so always make sure you are meeting their specific criteria.

Your proposal should typically be written in size 12 font and limited to around 15 pages in length.

Date Title of Your Research Project (or proposed title) Your name Supervisor’s name (if known) Department

Contents Introduction… Page 3 Research aims… Page 4 Literature review… Page 5 Research methods/methodology… Page 7 Outcomes and impact… Page 8 Budget… Page 9 Schedule… Page 9 References/Bibliography… Page 10

Introduction Introduce your research proposal with a brief overview of your intended research. Include the context and background of the research topic, as well as the rationale for undertaking the research. You should also reference key literature and include any relevant previous research you have done personally.

Research aims The aims of your research relate to the purpose of conducting the research and what you specifically want to achieve. Your research questions should be formulated to show how you will achieve those aims and what you want to find out through your research. “The objectives of this research project are to…..” “The following tasks will be undertaken as a part of the proposed research: Task 1 Task 2 Task 3, etc.”

Literature review Identify and expand on the key literature relating to your research topic. You will need to not only provide individual studies and theories, but also critically analyse and evaluate this literature.

Research methods/methodology Explain how you plan to conduct your research and the practical and/or theoretical approaches you will take. Describe and justify a sample/participants you plan to use, research methods and models you plan on implementing, and plans for data collection and data analysis. Also, consider any hurdles you may encounter or ethical considerations you need to make.

Outcomes and impact You don’t need to identify every specific/possible outcome from your research project but you should think about what some potential outcomes might be. Think back to any gaps you identified in the research field and summarise what impact your work will have on filling them. Make sure your assessors know why your research is important and ultimately worth investing time, money and resources into.

Budget Answer the following questions:

- What is the total budget for your project?

- Has funding already been acquired?

- If not, where is the money coming from and when do you plan to secure it?

Schedule You should outline the following 3 years and include achievable ‘deadlines’ throughout that period. Using your research aims as a starting point, itemise a list of deliverables with specific dates attached. You may choose to use a Gantt chart here.

References/Bibliography List all the references you used throughout your proposal and/or texts that will be relevant to your proposal here.

Example Research Proposal

To: Professor P. Brown From: Alissa Student Date: 30th April 2021 Proposed Research Topic: An investigation into the use of Multicultural London English by adolescents in South London

Change in present-day spoken British English is reportedly characterised by dialect levelling – the reduction of regional differences between dialects and accents. The details, however, are complex, with homogenisation across a region (Torgersen/Kerswill 2004) alongside geographical diffusion from a metropolis (Kerswill 2003). Yet there is also local differentiation and innovation (Britain 2005, Watson 2006). The role of London has been held to be central, with its influence claimed for the diffusion of a range of linguistic features, including T-glottalling (Sivertsen 1960) and TH-fronting (Kerswill 2003). In more recent years, there have been multiple large-scale sociolinguistic studies into the use of English by adolescents in London and the emergence of Multicultural London English (MLE) in particular. However, these studies (such as Kerswill et al. 2004-2007 and Kerswill et al. 2007-2010) focused on analysing language use in Hackney, a traditionally white working-class area with high immigration numbers in the twentieth century, located in East London. There have been fewer studies into the use of English and specifically the emergence of MLE among adolescents in South London. Areas of South London, such as Brixton, have high numbers of adolescents and, like Hackney, have been influenced by immigration movements throughout the twentieth century.

Research aims Through this research, I hope to investigate the language use of adolescents in the community of Brixton, enhancing our understanding of MLE in South London. My research questions are as follows:

- What are the linguistic features of the English spoken by adolescents in Brixton?

- What are the linguistic features of the English spoken by elderly residents in Brixton?

- Analyse the language of male participants versus female participants.

- Analyse the presence of linguistic features originally identified as characteristics of MLE in participants.

Methodology I will base my methodology on that used by Kerswill et al. (2004-2007, 2007-2010), analysing the natural language of adolescents in Brixton as well as a sample of elderly residents from the same region. The sample studied will include a mixture of male and female participants as well as participants from the three largest ethnicity demographics in Lambeth (according to the Lambeth council census, 2015), including White, Black, and Asian residents. My methodology consists of the following:

- Observe the language of adolescents in relaxed conversation-like interviews with friends and individually. I will attempt to conduct these interviews in an informal way and ask open-ended questions that encourage participants to converse in more detail and more naturally.

- Record these conversations and transcribe these conversations from these recordings. Transcriptions will be made using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to allow phonetic features to be identified and analysed.

- Using methods established in corpus linguistics, I will quantify the data and identify the rate of notable linguistic features in the group of participants, looking for any linguistic patterns relating to gender, ethnicity and age.

Outcomes and impact I expect this research to contribute to our understanding of Multicultural London English (MLE) in South London, an area of London not previously studied in great detail and one with different demographics to previously studied areas such as East London (Hackney). In the course of this research, which looks at the language of participants from a broad range of ethnic backgrounds and ages, it is possible that further variations and/or innovations in MLE will also be identified.

Schedule The first year of the project (30th September 2020-30th June 2021) will be spent conducting the necessary research with participants from Brixton and surrounding areas of South London. The first six months of the second year of the project (30th September 2021 – 31st March 2022) will be spent transcribing and collating the linguistic data. By the end of the second year of the project, the data will be analysed and I will begin writing up my findings, ready to be submitted in January 2023.

References Baker, Paul. 2006. Using corpora in discourse analysis. London: Continuum. BBC Voices Project http://www.bbc.co.uk/voices/. Cheshire, Jenny, Susan Fox, Paul Kerswill and Eivind Torgersen. 2008. Linguistic innovators: the English of adolescents in London. Final report presented to the Economic and Social Research Council. Cheshire, Jenny and Susan Fox. 2009. Was/were variation: A perspective from London. Language Variation and Change 21: 1–38. Cheshire, Jenny, Kerswill, Paul, Fox, Susan & Torgersen, Eivind. 2011. Contact, the feature pool and the speech community: The emergence of Multicultural London English. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15/2: 151–196. Clark, Lynn & Trousdale, Graeme. 2009 The role of frequency in phonological change: evidence from TH-fronting in east-central Scotland. English Language and Linguistics 13(1): 33-55. Gabrielatos, Costas, Eivind Torgersen, Sebastian Hoffmann and Susan Fox. 2010. A corpus–based sociolinguistic study of indefinite article forms in London English. Journal of English Linguistics 38: 297-334. Lambeth Council. 2015. Lambeth Demography 2015. https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/sites/default/files/ssh-lambeth-demography-2015.pdf. Johnston, Barbara. 2010. Locating language in identity. In Carmen Watt and Dominic Watt (eds.) Language and identities. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 29–36. Kerswill, Paul & Williams, Ann. 2002. ‘salience’ as an explanatory factor in language change: evidence from dialect levelling in urban England. In M. C. Jones & E. Esch (eds.) Language change. The interplay of internal, external and extra-linguistic factors. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 81–110. Kerswill, Paul, Torgersen, Eivind & Fox, Susan. 2008. Reversing “drift”: Innovation and diffusion in the London diphthong system. Language Variation and Change 20: 451–491. Kerswill, Paul, Cheshire, Jenny, Fox, Susan and Torgersen, Eivind. fc 2012. English as a contact language: the role of children and adolescents. In Hundt, Marianne & Schreier, Daniel (eds.) English as a contact language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Labov, William. 2007. Transmission and diffusion. Language 83: 344–387. Llamas, Carmen. 2007. Field methods. In Carmen Llamas, Louise Mullany and Peter Stockwell (eds.). The Routledge companion to sociolinguistics. London: Routledge, pp. 12– 17. Pichler, Heike and Torgersen, Eivind. It’s (not) diffusing, innit?: The origins of innit in British English. Paper presented at NWAV 38, University of Ottawa, October 2009. 34 Rampton, Ben. 2010. Crossing into class: language, ethnicities and class sensibility in England. In Carmen Llamas and Dominic Watt (eds.) Language and identities. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 134–143. Sebba, Mark. 1993. London Jamaican. London: Longman. Spence, Lorna. 2008. A profile of Londoners by country of birth: Estimates from the 2006 Annual Population Survey. London: Greater London Authority. Torgersen, Eivind & Kerswill, Paul 2004. Internal and external motivation in phonetic change: dialect levelling outcomes for an English vowel shift. Journal of Sociolinguistics 8: 23–53. Torgersen, Eivind, Gabrielatos, Costas, Hoffmann, Sebastian and Fox, Sue. (2011) A corpus-based study of pragmatic markers in London English. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 7: 93–118. Wells, John C. 1982. Accents of English, Vols. I–III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wiese, Heike. 2009. Grammatical innovation in multiethnic urban Europe: New linguistic practices among adolescents. Lingua 119: 782–806. Winford, Donald. 2003. An Introduction to Contact Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Section examples

Example introduction.

In this example, the candidate is applying for an Executive PhD programme that requires them to have both work experience and academic experience. The candidate focuses their introduction on the background of the research area they are proposing and relates this to their own experiences and deep understanding of the topic.

Recent developments in the global economy have exposed weaknesses and vulnerabilities in commodity-dependent emerging economies. The country of Azerbaijan has been affected significantly by a radical fall in oil prices; this has revealed an inability, and to a certain extent the incapacity, of the economy to respond to this new reality. As a result, the local currency has depreciated to more than half its value in a two-year period and the country’s balance of payments gap has reached five billion US dollars within the last year. While Azerbaijan is a small country in the global economy, many of these same problems are occurring in other emerging economy countries with primary commodity dependency, and have occurred in cycles in the past. The context of this crisis might be different, but the same themes reoccur throughout history. Today the price of oil, tomorrow the collapse of the Euro currency or a dramatic increase in the price of food. Any scenario emphasises the need to build comprehensive institutions which encourage economic growth alongside a viable macro-risk management system to ensure stability all the while balancing government with the needs of businesses. During my MBA, I was introduced to the theories underpinning modern finance. I was given a toolset with which I would answer many of the queries I have about international finance. In applying for the Executive PhD programme, I want to pursue my interest in ensuring economic growth, prudent banking regulation and the building of a macro-risk management system for developing countries. Over the last couple of years, I have been involved in anti-crisis efforts and the large-scale reorganisation of the Azeri financial system. At present, the Azerbaijani economy is suffering from a “Dutch disease” problem where the previous economic development of the oil and natural resources sector has caused a decline and lack of development in all other sectors (including manufacturing and agriculture). Other countries with similar problems include Gulf States, Nigeria, Venezuela, Ecuador and Russia. GDP is estimated to have contracted by 3% in 2016 and the budget deficit has reached 4.6%. The role of the state sector has increased significantly and the state now has an 8% of GDP deficit. Previous models have always assumed a recovery in oil prices, but this has not materialised and forecasts are increasingly vague. In a world of persistently low oil prices and declining Azerbaijani output, the country has to make progress on a sizable structural reform agenda. My research project would comparatively study the three principal areas of macroeconomic weakness in the Azerbaijani economy where reforms are slated to take place over the coming years, comparing them with other commodity-dependent economies; these areas would be: the challenging business environment (including strategic trade, labour market rigidity and transport problems), problems in macroeconomic policy coordination, and banking sector weakness. The key outcome of this policy research would be maintaining a policy of economic growth, poverty reduction and avoiding the middle-income trap in Azerbaijan. Conducting further research into these issues would allow me to further my macroeconomic knowledge and I believe would allow me to ultimately be promoted to a more senior financial position within the Azerbaijani civil service.

Example Research Questions

In this example, the candidate is proposing research that involves working with children in order to study the effects of creative writing on children’s development. The overall objective is to explore the impact upon the young child’s creative writing/storytelling behaviours of the views and beliefs of significant others across home, pre-school and school settings.

What is the adult’s role when supporting young children with creative writing? What forms of child/ adult interaction support rather than constrain young children’s episodes of creative writing? How does the adult ‘tune in’ to young children’s needs in relation to storytelling? How does the adult recognise when it is appropriate to intervene? Does the form of interaction appear to change with the age or perceived storytelling ability of the child? Is the form of interaction between child and adult influenced by gendered behaviours? How does the environment best support child/ adult interaction? (Time, space, organisation of materials.) Does adult support for young children’s creative writing differ from support given in relation to other activities? How important is the adult’s awareness/ knowledge of the child’s holistic needs when supporting young children’s storytelling behaviours? How important is the adult’s awareness/ knowledge of the child’s particular patterns of meaning making when supporting young children’s creative writing behaviours? What is the impact upon young children’s creative writing of an adult’s own experience/ knowledge and understanding of storytelling behaviour?

Example Risk Analysis

In this example, the candidate is proposing research that involves working with children in order to study the effects of creative writing on children’s development. When working with children, it is particularly important to conduct a risk assessment and take care in ensuring all laws and regulations are upheld to ensure all child participants are safeguarded.

Particular attention will be paid to the role of the children within the project. It is expected that the children taking part in the study will be aged between 5 and 7 years. It is expected that involvement in episodes of creative writing activity will be voluntary and that, given that the research is taking place in a familiar school context and that the practitioners are part of that context, the normality of the children’s experience can be maintained. It is anticipated that each school will have an agreed policy on gaining permission for the taking of video and digital images within the setting which will be adhered to. In many settings, parents sign a consent form when the children begin attending the setting agreeing to their child being videoed. In relation to this research project, following editing of any video material or digital images, it will be necessary to gain additional consent from parents of featured children if the material is to be published. No child will be videotaped or photographed where permission by parents/carers has been refused. The reason for the use of the video camera/digital camera will be explained simply to the children. They will be told that a particular activity is being videoed so that they can choose not to take part. Time must be found for children to see the data collected if the children request this. The original materials/drawings will remain in the setting but the researcher will make colour photocopies of all drawings. The original videotapes/digital images, if taken by the adult participants, will remain with the school and the researcher will make a copy. Videotapes/digital images taken by the researcher will remain with the researcher but will be made available to the participants. Following observation of videotapes/digital images by practitioners and researchers it is anticipated that only clips of video and digital images agreed by all parties will eventually be retained. Both the school and the researcher will have copies of the edited material. All participants will be assured that their names and their settings will not be divulged. In written documentation, the children’s first names will be changed and surnames will not be used. Practitioners will be asked not to use children’s surnames when videoing.

Further resources

There are many resources available if you’re looking for help developing your PhD research proposal. Some universities, such as York St John University and the Open University, provide examples of research proposals that you can use as a basis on which to write your own PhD proposal. Most university departments also publish detailed guidelines on what to include in a research proposal, including which sections to include and what topics they are currently accepting proposals on.

The Profs’ PhD application tutors can also provide relevant example research proposals and support to help you structure your own PhD research proposal in the most effective way. More than 40% of all of our tutors have PhDs themselves, with many having worked as university lecturers, thesis supervisors, and professors at top universities around the world. Thanks to the expertise of our tutors and the consistent support our team provides, 95% of our students get into their first or second choice university. Get in touch with our postgraduate admissions department today to find out how we can help you.

How do I create a PhD timescale/timeline?

Many universities request that PhD applicants submit a timescale/timeline detailing how they plan to spend the 3-4 years on their research. There are many ways you can do this, but one of the most popular methods (and one that is often suggested by university experts) is to use a Gantt chart. A Gantt chart is a useful way of showing tasks displayed against time. On the left of the chart is a list of the activities and along the top is a suitable time scale. Each activity is represented by a bar; the position and length of the bar reflect the proposed start date, duration and end date of the task.

How long does it take to write a research proposal?

The amount of time you need to write a research proposal will depend on many factors, including the word count, when your application deadline is, and how developed your research plan is. On average, it takes applicants about 2-3 months to research, write, rewrite, edit, and submit a strong proposal.

How do I find a research proposal topic?

Choosing a research topic is one of the most important stages of submitting a PhD research proposal. Primarily, you should look to choose a topic that you are interested in/that you care about; you will be researching this topic for 3-4 years at least, so it’s important that you are invested in it. Secondly, your research topic needs to be narrow enough that it is manageable. If your topic is too broad, there will be too much information to consider and you will not be able to draw concise conclusions or focus deeply enough.

In order to find a research proposal topic, first look at the areas that you have previously studied. Reviewing past lecture notes and assignments can be a helpful way of finding inspiration. Background reading can also help you explore topics in more depth and limit the scope of your research question. You can also discuss your ideas/areas of interest with a lecturer or professor, potential dissertation supervisor, or specialist tutor to get an academic perspective.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Did you enjoy reading PhD Research Proposal Template With Examples? Sign up to our newsletter and receive a range of additional materials and guidance that can help advance your learning or university application.

Please agree to the terms to subscribe to the newsletter

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices.

Browse more “ ” related blogs:

Emily Watson

Contact the profs.

Or fill in the form below and we will call you:

What level of study?

What do you need help with, what subject/course , which university are you applying to.

*Please enter a subject/course

*Please enter which university you are studying

How much tutoring do you need?

*Please be aware that we have a 5-hour minimum spend policy

What are your grades ?

*Please enter the subject you are studying and your predicted grades

Please provide additional information

The more detailed this is, the quicker we are able to find the perfect tutor for you.

*Please fill in the empty fields

Contact details:

*Please enter a valid telephone number

*Please enter a valid country code

*Please enter a valid email address

*Please make your email and confirmation email are the same

*Please complete the captcha below

We do not facilitate cheating or academic misconduct in any way. Please do not call or request anything unethical from our team.

The UK’s highest rated tuition company since 2016 on Trustpilot

How to Write a PhD Proposal in 7 Steps

Learn the key steps to crafting a compelling PhD proposal. This guide breaks down the process into 7 manageable parts to help you succeed.

Jun 11, 2024

How to Write a PhD Proposal in 7 Steps: A Proven Guide

Embarking on a PhD journey is a significant academic and personal commitment, and the first crucial step in this process is writing a compelling research proposal. A PhD research proposal serves as a detailed plan or ‘blueprint’ for your intended study.

It outlines your research questions, aims, methods, and proposed timetable, and it must clearly articulate your research question, demonstrate your understanding of existing literature, and outline your proposed research methodology. This guide will walk you through seven essential steps to craft a successful PhD research proposal.

Understanding the Research Proposal

What is a research proposal.

A research proposal is a comprehensive plan that details your intended research project. It serves as a roadmap for your study, laying out your research questions, objectives, methods, and the significance of your proposed research. It is crucial for securing a place in a PhD program and for gaining the support of potential supervisors and funding bodies.

A PhD research proposal must clearly articulate your research question, and your research context, demonstrate your understanding of existing literature, and outline your proposed research methodology. This document showcases your ability to identify and address a research gap, and it sets the stage for your future research endeavors.

Importance of a Well-Written Research Proposal

A well-written research proposal can make a strong impression and significantly increase your chances of acceptance into a PhD program. It showcases your expertise and knowledge of the existing field, highlighting how your research will contribute to it. A successful research proposal convinces potential supervisors and funders of the value and feasibility of your project.

The importance of a good research proposal extends beyond the application process. It serves as a foundation for your entire PhD journey, guiding your research and keeping you focused on your objectives. A clear and concise proposal ensures that you have a well-thought-out plan, which can save you time and effort in the long run.

Step 1: Conduct a Literature Review

Reviewing the Current State of Research in Your Field

A literature review is a critical component of your next research study or proposal. It involves a comprehensive survey of all sources of scientific evidence related to your research topic. The review should be structured intelligently to help the reader grasp the argument related to your study about other researchers’ work. Remember the five ‘C’s while writing a literature review: context, concept, critique, connection, and conclusion. This approach ensures that your literature review is thorough and well-organized.

To begin, search for relevant literature using databases such as Google Scholar, JSTOR, and PubMed. Read review articles and recent publications to get a sense of the current state of research in your field. Pay attention to the key themes, theories, and methodologies used in previous research by other researchers. This will help you identify gaps in the existing literature that your proposed research can address.

Identifying Gaps and Opportunities for Proposed Research

Your literature review should convey your understanding and awareness of the key issues and debates in the field. It should focus on the theoretical and practical knowledge gaps that your work aims to address. A well-written literature review not only demonstrates your expertise but also highlights the novelty and significance of your proposed research.

As you review the literature, take note of recurring findings, themes, and gaps in the research. Identify areas where there is a lack of empirical evidence or where existing theories have not been adequately tested. These gaps represent opportunities for your proposed research to make a meaningful contribution to the field.

Step 2: Define Your Research

Background and Rationale: Setting the Context for Your Research

The background and rationale section sets the stage for your research by specifying the subject area of your research and problem statement. This includes a detailed literature review summarizing existing knowledge surrounding your research topic. This section should discuss relevant theories, models, and bodies of text, establishing the foundation for your research question.

In this section, provide a brief overview of the historical and theoretical context of your research topic. Explain why this topic is important and how it fits into the broader field of study. Discuss any key debates or controversies that are relevant to your research problem. This will help to situate your research within the existing body of knowledge and demonstrate its significance.

Research Aims and Objectives: Clarifying the Purpose of Your Study

In this section, clearly state the problems your project intends specific aims to solve. Outline the measurable steps and outcomes required to achieve the aim. Explain why your proposed research is worth exploring, emphasizing its potential contributions to the field.

Your research aims and objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). Clearly articulate the research question or hypothesis that you intend to investigate. Break down your research aims into specific objectives that will guide your study. This will provide a clear roadmap for your research and help to keep you focused on your actual research goals.

Step 3: Develop Your Research Design and Methodology

Research Design: Outlining Your Approach

Your research design and methodology section should provide a clear explanation of your research methods and procedures. Discuss the structure of your research design, including potential limitations and challenges. This section should offer a robust framework for how you plan to conduct your study.

Describe the overall research design, including whether your study will be qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods. Discuss the rationale for choosing this design and how it will help you address your research questions. Provide details on the specific methods you will use for data collection and analysis, and explain how these methods are appropriate for your study.

Methodology: Selecting the Right Methods for Your Study

Outline the methods you’ll use to answer each of your research questions. A strong methodology is crucial, especially if your project involves extensive collection and analysis of primary data. Demonstrate your awareness of the limitations of your research method, and qualify the parameters you plan to introduce.

Discuss the sampling methods, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures you will use in your study. Provide a detailed plan for how you will collect and analyze your data, including any tools or instruments you will use. Address any potential ethical issues and explain how you will mitigate them. This will show that you have thoroughly considered the practical aspects of your research and are prepared to address any challenges that may arise.

Step 4: Consider Ethical Implications and Budget

Ethical considerations: addressing potential risks and concerns.

Ethical considerations are paramount, especially in medical or sensitive social research. Ensure that ethical standards are met, including the protection of participants’ rights, obtaining informed consent, and the institutional review process (ethical approval). Addressing these issues upfront shows your commitment to conducting responsible research.

Discuss any potential risks to participants and how you will mitigate them. Describe the process for obtaining informed consent and ensuring confidentiality. If your research involves vulnerable populations or sensitive topics, provide additional details on how you will protect participants’ rights and well-being. This will demonstrate your commitment to ethical research practices and help to build trust with potential supervisors and funders.

Budget: Estimating Costs and Resources for Your Research

When preparing a research budget, predict and cost all aspects of the research, adding allowance for unforeseen issues, delays, and rising costs. Justify all items in the budget to show thorough planning and foresight.

Provide a detailed breakdown of the costs associated with your research, including expenses for data collection, travel, equipment, and materials. Include any anticipated costs for hiring research assistants or consultants, as well as costs for data analysis and dissemination. Justify each item in the budget, explaining why it is necessary for your research. This will show that you have carefully considered the financial aspects of your project and are prepared to manage the resources required for your study.

Step 5: Create a Timetable and Appendices

Timetable: outlining milestones and deadlines.

The timetable section should outline the various stages of your research project, providing an approximate timeline for each stage, including key milestones. Summarize your research plan and provide a clear overview of your research timeline to demonstrate your ability to manage and complete the project within the allotted time.

Create a detailed timeline that outlines the major phases of your research, including literature review, data collection, data analysis, and writing. Include specific milestones and deadlines for each phase, and provide a realistic estimate of the time required for each task. This will help you stay on track and ensure that your research progresses smoothly.

Appendices: Supporting Documents and Materials

Appendices support the proposal and application by including documents such as informed consent forms, questionnaires, measurement tools, and patient information in layman’s language. These documents are crucial for providing detailed information that supports your research proposal.

Include any additional documents that support your research proposal, such as letters of support from potential supervisors, sample questionnaires, and data collection instruments. Provide detailed information on any measurement tools or protocols you will use in your study. This will show that you have thoroughly planned your research and are prepared to carry out the proposed study.

Step 6: Write Your Research Proposal

Crafting a clear and concise research proposal.

Your research proposal is a key document that helps you secure funding and approval for your research. It is a demonstration of your research skills and knowledge. A well-written proposal can significantly increase your chances of getting accepted into a PhD program.

Begin research proposals by writing a clear and concise introduction that provides an overview of your research topic and its significance. Summarize your research aims and objectives, and provide a brief outline of the structure of your proposal. Use clear and concise language throughout the proposal, and avoid jargon or technical terms that may be unfamiliar to readers.

Ensuring Coherence and Consistency Throughout Your Proposal

Follow a logical and clear structure in your proposal, adhering to the same order as the headings provided above. Ensure that your proposal is coherent and consistent, following the format required by your university’s PhD thesis submissions. This consistency makes your proposal easier to read and more professional.

Use headings and subheadings to organize your proposal and make it easy to navigate. Ensure that each section flows logically from one to the next and that there is a clear connection between your research aims, objectives, and methods. Proofread your proposal carefully to ensure that it is free of errors and that the language is clear and concise.

Step 7: Finalize and Submit Your Research Proposal

Final checks: ensuring completeness and accuracy.

Before submitting your research proposal, ensure that you have adhered to the required format and that your proposal is well-written, clear, and concise. Double-check for completeness and accuracy to ensure that your proposal effectively communicates your research idea and methodology.

Review your proposal carefully to ensure that it includes all required sections and that each section is complete and accurate. Check for any inconsistencies or gaps in the information, and ensure that all references are properly cited. Ask a colleague or supervisor to review your proposal and provide feedback before submitting it.

Submitting Your Research Proposal: Tips for Success

A research proposal is a standard means of assessing your potential as a doctoral researcher. It explains the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of your research, showcasing your expertise and knowledge of the existing field, and demonstrating how your research will contribute to it. Ensure that your PhD research proposal clearly articulates your research question, demonstrates your understanding of existing literature, and outlines your proposed research methodology.

When submitting your research proposal, follow the guidelines provided by your university or funding body. Ensure that you have included all required documents and that your proposal is formatted correctly. Pay attention to any submission deadlines, and plan to ensure that you have enough time to complete and review your proposal before submitting it.

Writing a PhD proposal is a rigorous process that requires careful planning, detailed knowledge of your field, and a clear vision for your research project. By following these seven steps, you can craft a compelling and successful research proposal.

Remember to conduct a thorough literature review, define your research clearly, develop a robust research design and methodology, consider ethical implications and budget, create a detailed timetable and appendices, write a clear and concise proposal, and finalize and submit with confidence.

This guide provides a proven framework for prospective PhD students to write a strong and effective research proposal, increasing their chances of acceptance into a PhD program and securing the necessary support and funding for their research.

Embarking on a PhD journey is both challenging and rewarding. The process of writing a research proposal helps you to clarify your research goals, plan your study, and communicate your ideas to others. A well-crafted research proposal writing, not only increases your chances of acceptance into a PhD program but also sets the stage for a successful research project.

Throughout this guide, we have emphasized the importance of conducting a thorough literature review, defining your research aims and objectives, and developing a clear and robust research design and methodology. We have also highlighted the need to consider ethical implications and budget, create a detailed timetable and appendices, and write a clear and concise proposal. Finally, we have provided tips for finalizing and submitting your research proposal.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your research proposal is well-written, comprehensive, and compelling. This will not only help you to secure a place in a PhD program but also provide a solid foundation for your future research endeavors.

Remember, writing a research proposal is a process that takes time and effort. Be patient and persistent, and seek feedback from colleagues, supervisors, and mentors. Use the resources available to you, such as academic journals, databases, and online tools, to support your research and writing. With careful planning and dedication, you can write a successful research proposal that sets the stage for a rewarding and fulfilling PhD journey.

Easily pronounces technical words in any field

Academic Writing

dissertation proposal

Graduate School

PhD proposal

research proposal

Recent Articles

9 Must-Have Apps for Students

Discover the 9 must-have apps for students in 2024. These apps are designed for students to stay organized and be productive.

Glice Martineau

May 22, 2024

Productivity

Overcoming Test Anxiety: Ways to Manage and Conquer Your Fears

Learn how to manage test anxiety and improve your exam performance. Discover practical strategies to reduce stress and boost confidence.

Derek Pankaew

Nov 14, 2024

Coping strategies

Exam stress management

Mindfulness Techniques

Relaxation Exercises

Test anxiety solutions

What is Lifelong Learning? 5 Benefits of Being a Lifelong Learner

Discover the concept of lifelong learning and its 5 key benefits. Boost your personal and professional growth with continuous learning.

Amethyst Rayne

Jun 28, 2024

Continuous Learning

Lifelong Learning

Personal Fulfillment

Professional Development

Narakeet vs Listening: Which is the Best Text to Speech App for You?

Compare Narakeet and Listening.com TTS apps: Features, strengths, and ideal use cases. Find the best text-to-speech solution for your needs.

Jul 24, 2024

Speech Synthesis

Text-to-Speech Apps

Public Documents

Association between Traffic-Related Air Pollution in Schools and Cognitive Development in Primary School Children: A Prospective Cohort Study

Jordi Sunyer, Mikel Esnaola, Mar Alvarez-Pedrerol, Joan Forns, Ioar Rivas, Mònica López-Vicente, Elisabet Suades-González, Maria Foraster, Raquel Garcia-Esteban, Xavier Basagaña, Mar Viana, Marta Cirach, Teresa Moreno, Andrés Alastuey, Núria Sebastian-Galles, Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, Xavier Querol

Mar 3, 2015

Atmospheric Sciences, Climate Science, Environmental Studies

The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014

Ana Pilar Betrán , Jianfeng Ye, Anne-Beth Moller, Jun Zhang,A. Metin Gülmezoglu, Maria Regina Torloni

Feb 5, 2016

Epidemiology, Health and Medicine, Public Health

The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: A study of seven middle-income countries in Asia

Cuiyan Wang, Michael Tee, Ashley Edward Roy, Mohammad A. Fardin, Wandee Srichokchatchawan, Hina A. Habib, Bach X. Tran, Shahzad Hussain, Men T. Hoang, Xuan T. Le, Wenfang Ma, Hai Q. Pham, Mahmoud Shirazi, Vipat Kuruchittham

Feb 11, 2021

COVID-19 Research, Health and Medicine, Mental Health, Psychological Impact

The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Ashkan Afshin , José L. Peñalvo , Liana Del Gobbo, Jose Silva, Melody Michaelson, Martin O'Flaherty, Simon Capewell, Donna Spiegelman, Goodarz Danaei, Dariush Mozaffarian

Mar 1, 2017

Health Policy, Health and Medicine, Public Health

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Tress Academic

#112: PhD project-planning quick-start

February 15, 2022 by Tress Academic

Let’s get straight to the point: If you realistically want to have a chance of finishing your PhD on time, you’ll have to plan your project. More specifically, you have to apply project management techniques and appoint yourself the manager of that project. Many PhD candidates have trouble setting up and following a project plan. That is why in this blogpost, we’ll let you know what it means to manage your PhD project and we’ll share an awesome free worksheet: 6 steps to outline a PhD project plan . With this, you can start drafting your project plan without struggle and endless searching for the right procedure.

My experiences with project planning

When I set out to apply for a scholarship to fund my PhD project, my supervisor, a professor at the University of Heidelberg, told me to describe exactly what I wanted to achieve in my project, and to set up a Gantt-Chart so my proposal would convince the funding agency that my project was worth the investment. My professor was tight-lipped and I did not get any further information on how to work out my project plan. I dived into the university library for the latest project-management guides, and it took a lot of time to figure it all out and come up with a reasonable plan for my PhD project. I got the funding for the project, and once I started, I used my plan to guide me throughout my project. I adjusted it every now and then, but it helped me never lose sight of my goals and to finish within the 3 years that I had.

I have used project plans ever since. In the 12 years that I have worked as a scientist, there were many plans for small projects within my own group or institute, as well as for large multinational EU-framework funded project clusters. And since running TRESS ACADEMIC , whenever we set up a new course or revise our website, the first thing we do is set up a project plan. We even have mini-project plans for our weekly blog posts with the exact tasks we have to do and when they need to be completed. For me, this has become second nature: No project without a plan.

Common myths around project planning for PhD projects

1. believing you don’t know enough.

Many PhD students don’t devise a plan because they think they don’t know enough about their project–particularly what the end results might be. That is a very common excuse to avoid thinking about the goals and outcomes of the project, as well as the entire process that will lead you there. You can read more about this and other common objections on the SMART ACADEMICS BLOG post no. 47: Plan your project – save your PhD!

2. Believing a plan is set in stone

In other words, you are afraid that once the plan is set, you lose all freedom and flexibility in your research.

Don’t think that once the plan is drawn up, your project will be carried out in this exact way. None of my projects were ever carried out exactly as I had initially planned. The goal is not to set-up regulations that dictate your every move, but to set-up a plan that will steer your project along the correct path. Your plan helps you make informed decisions on where to take your project at any point in time. You can stick to the plan or adjust it if you determine that a deviation is superior to what you have initially planned. This is how your project will evolve and improve over time.

3. Believing it’s better to wait and see what happens

There is still a wide-spread belief that you start a PhD and just see what comes your way or what will develop once your supervisors give you some initial input. This is blind-trust that the brilliant scientists around you will show you the safe route to finish on time with stellar results. Hint: They won’t, and it’s not their task. While I hope that your supervisor will give you input and bounce around ideas with you (that is indeed their task), don’t expect them to run this project for you. This is your PhD, not theirs.

4. Believing you don’t need a personal plan for your PhD because there is already one for the bigger project you’re working in

Are you a PhD working in a larger research project with many collaborating scientists? Is your PhD project only focusing on one aspect among many ? When you get the project plan for the bigger project (or the part that your supervisor is responsible for) handed to you, you may think: Great, that’s my plan! I don’t need a separate one for myself. Wrong. Although your PhD will take place under the umbrella of this bigger project, you need to sit down and identify exactly what you are going to do that a) serves the goals of the overall project b) merits a PhD.

If you fail to plan you plan to fail